Lecture 14 - Stack / Heap

Logistics - Exam

- You survived the exam!

- I will have grades to you by Friday, probably sooner

- You'll have 1 week to do corrections and/or ask for an oral redo of a topic

- I dropped the hand-coding weight from ~40% to ~20% (it won't hurt you)

Logistics - Exam

Corrections requirements

- Like HW1 corrections

- An explanation of what you misunderstood and what you learned since

- A completely correct answer

- No partial credit

Oral exam option - tweaked since the syllabus

- In addition to corrections for ONE of part of the exam, you can meet with me for a short in-person conversation where we discuss your insight, you answer some related questions, and have the opportunity to recover more points (up to a cap of 90% for the section).

- Some examples:

- You received 7/21 points (33%) for hand-coding. With corrections you can reach 66%. If you come in for an oral exam you may receive additional credit, for a final section score between 66% and 90%.

- You received 15/18 ponts on Part 1 (83%). With corrections you can reach 92%. You can't improve your score on this section with an oral exam.

- With the corrections assignment I'll ask you to elect which section, if any, you'd like to go over together and I'll coordinate scheduling.

Logistics - other stuff

- HW3 is due tonight at midnight - Zach (from A1) has office hours 1:30-3:30 for last-minute questions

- HW2 corrections are due Thursday night

- HW4 will be posted Friday, due two weeks later

Learning Objectives

- Today: We're going to peek under the hood of how computers actually store and manage data

By the end of today, you should be able to:

- Explain what computer memory (RAM) is and how it works

- Understand what memory addresses are and why they matter

- Distinguish between stack and heap memory allocation

- Connect these concepts to Rust code you've already written

- Understand why Rust's approach to memory management is different (and better!)

What is computer memory?

Where are x, name, and scores actually stored when your program runs?

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let x = 42; let name = "Alice".to_string(); let scores = [85, 92, 78]; }

What's the difference between RAM and storage (hard drive)?

| RAM (Memory) | Storage (Hard Drive/SSD) |

|---|---|

| Super fast (nanoseconds) | Much slower (microseconds to milliseconds) |

| Temporary (lost when power off) | Permanent (survives power off) |

| Small (8-64 GB typical) | Large (500 GB - 4 TB typical) |

Physical difference: RAM uses electronic circuits (transistors/capacitors) that can switch instantly, while storage uses mechanical parts (spinning disks) or slower flash memory cells.

CPU + RAM relationship: The CPU (processor) is like the "brain" that does all the actual work - it reads instructions and data from RAM, processes them, and writes results back to RAM. You can think of of RAM as the CPU's "desk" where it keeps everything it's currently working on.

Key idea: Your program runs entirely in RAM! - Storage is only used to load your program into RAM initially.

A helpful metaphor for RAM

Your RAM is like an organized city made up of buildings and units

- Each unit has a unique address (like "Building A, Floor 5, Apt 12")

- Each unit can hold one piece of data (like one number, one character)

- The computer can look up any unit instantly if it knows the address

- Everyone is renting - limited space / data is lost with power off

- You get there on a bus!

When your program runs, ALL your data has to live somewhere in this city

Memory Addresses - Like Street Addresses

Every location in memory has a unique address -

Memory Address | Data Stored There

------------------|------------------

0x7fff5fbff6bc | 42

0x7fff5fbff6c0 | 'H'

0x7fff5fbff6c4 | 'e'

0x7fff5fbff6c8 | 'l'

0x7fff5fbff6cc | 'l'

0x7fff5fbff6d0 | 'o'

- Addresses are written in hexadecimal (base 16) - that's why they go up to "f"

- The computer uses these addresses to find your data super quickly

- Pointers are just variables that store memory addresses instead of values

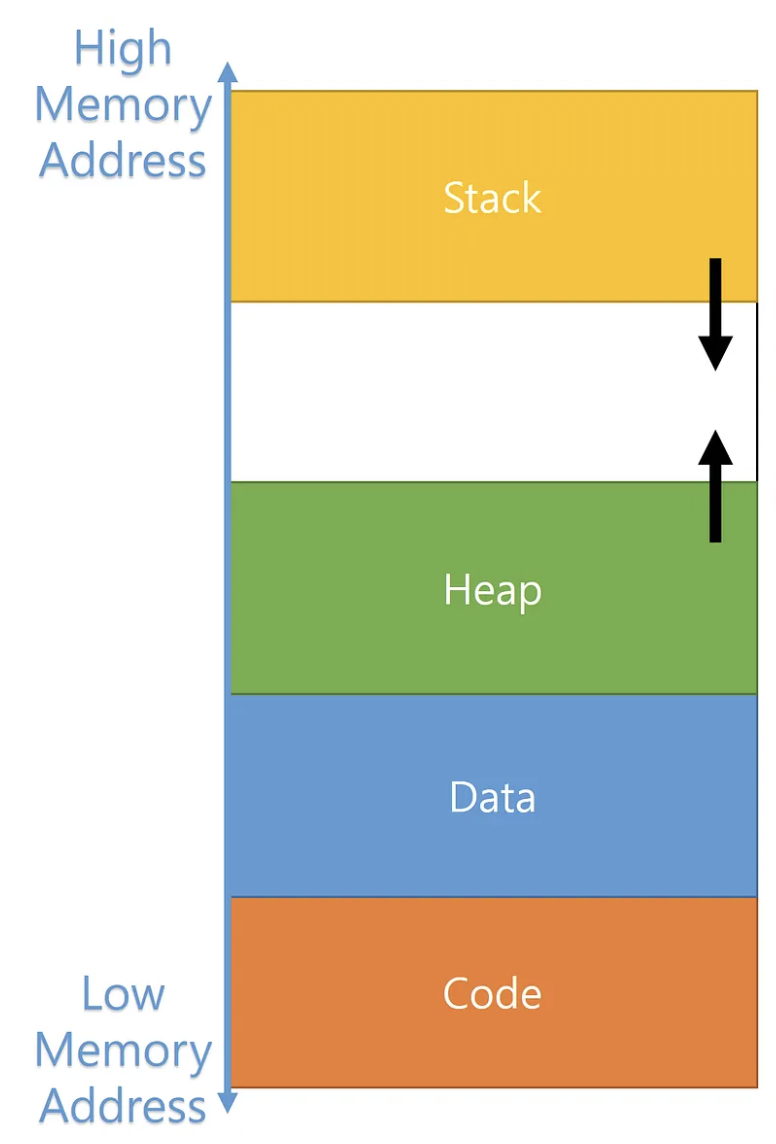

How Memory is Organized - The Big Picture

When your program runs, memory is organized into different "neighborhoods" for different purposes:

It's as if the city has different districts (from low addresses to high addresses):

- Text/Code - Where your compiled Rust functions live ("business district"?)

- Static Data - Where global constants live ("city hall"?)

- Heap - Where dynamic data lives (like "storage units" - rent them when you need them)

- Stack - Where local variables live temporarily (most like dorms - people move in and out)

We'll mostly care about Stack vs. Heap

Why Should You Care?

Programs need to:

- Get memory when they need to store data ("move in")

- Give it back when they're done with it ("move out")

If programs don't give memory back your computer/program slows down and eventually crashes!

(In the housing analogy, there's a housing shortage, homelessness, and eventually a proletariat uprising?)

Three Approaches to Memory Management

Different programming languages handle this differently:

-

Manual (C/C++): "You figure it out!"

- Programmer manually asks for memory and gives it back (C:

malloc/free) - Super fast, but easy to make dangerous mistakes

- Programmer manually asks for memory and gives it back (C:

-

Garbage Collection (Python/Java): "I'll handle it automatically!"

- Language automatically cleans up unused memory

- Safe but can cause random slowdowns

-

Ownership (Rust): "I'll help you get it right!"

- Compiler enforces rules to prevent mistakes

- Fast AND safe - best of both worlds!

This is why Rust can seem picky sometimes - it's preventing memory bugs!

Stack vs. Heap: The Two Main Memory Types

The Stack: Like a dorm, but also... like a literal stack of plates

Key idea: Last thing you put on, first thing you take off

fn main() { // Stack: [ ] let x = 42; // Stack: [x=42 ] let y = true; // Stack: [x=42, y=true] println!("{}", x); } // Stack: [ ] ← Everything cleaned up automatically!

Stack characteristics:

- Super fast - just "put on top" or "take off top"

- Limited size - like a small tower of plates

- Automatic cleanup - when a function ends, its "plates" are removed

- Size must be known - each "plate" is a fixed size

Most Rust data you've seen lives on the stack: i32, bool, char, arrays, tuples

Stack Frames: Organized Sections

Each function call gets its own organized section called a stack frame

Stack frame holds all the data for one function call:

- Function parameters

- Local variables

- Return address (where to go back when function ends)

- Other bookkeeping info

Stack Memory:

┌─────────────────┐ ← Top of stack

│ Function C │ ← Stack frame for Function C

│ parameters │

│ local vars │

│ return info │

├─────────────────┤

│ Function B │ ← Stack frame for Function B

│ parameters │

│ local vars │

│ return info │

├─────────────────┤

│ Function A │ ← Stack frame for Function A (main)

│ parameters │

│ local vars │

│ return info │

└─────────────────┘ ← Bottom of stack

When a function ends, its entire stack frame gets removed instantly!

A short example of stack frames

When you call a function, it gets its own stack frame:

fn main() { // Stack: [main's stack frame] let x = 5; let result = double(x); // Stack: [main's frame][double's frame] println!("{}", result); } // Stack: [main's frame] ← double's frame is gone! fn double(n: i32) -> i32 { let doubled = n * 2; // This lives in double's stack frame doubled }

Stack Overflow - A Real Problem!

What happens if you make too many function calls?

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn recursive_function(n: u32) -> u32 { if n == 0 { 0 } else { recursive_function(n - 1) // Each call adds a new "plate" to the stack! } } // This will crash your program: recursive_function(1_000_000); // Too many "plates"! }

This is where the name "Stack Overflow" (the website) comes from!

The Heap: Like a Storage Unit Facility

Key idea: Rent storage space when you need it, different sizes allowed

fn main() { let name = "Alice".to_string(); // The actual "Alice" lives on the heap! let scores = vec![85, 92, 78, 96, 88]; // These numbers live on the heap! // name and scores themselves are on the stack, // but they contain "addresses" pointing to heap data }

Heap characteristics:

- Flexible size - can grow and shrink as needed

- Slower access - have to "drive to the storage unit"

- Manual management needed - someone has to "return the keys"

- Much larger - way more space available than stack

Rust data that lives on the heap: String, Vec, HashMap, Box

Stack vs. Heap

| Stack 🍽️ | Heap 📦 |

|---|---|

| Fixed size, known at compile time | Variable size, can grow/shrink |

| Super fast access | Slower access (follow pointer) |

| Automatic cleanup | Manual management needed |

| Limited space | Lots of space |

i32, bool, arrays, tuples | String, Vec, HashMap, etc. |

String vs &str - Finally Explained!

We can explain this a bit more now with stack/heap:

String: Owned Text on the Heap

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let name = "Alice".to_string(); // or String::from("Alice") }

What happens in memory:

Stack: Heap:

┌─────────────┐ ┌─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┐

│ name │ │ 'A' │ 'l' │ 'i' │ 'c' │ 'e' │

│ ├ ptr ──────┼─────────▶│ │ │ │ │ │

│ ├ len: 5 │ └─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┘

│ └ cap: 5 │

└─────────────┘

- String = the metadata on the stack (pointer, length, capacity)

- Actual text = lives on the heap

- You own it = you can modify it, and Rust will clean it up for you

&str: Borrowed Text (Points to Existing Data)

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let greeting = "Hello"; // This is &str }

What happens in memory:

Stack: Program Binary (Text Section):

┌─────────────┐ ┌─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┐

│ greeting │ │ 'H' │ 'e' │ 'l' │ 'l' │ 'o' │

│ ├ ptr ──────┼─────────▶│ │ │ │ │ │

│ └ len: 5 │ └─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┘

└─────────────┘

- &str = just a pointer and length on the stack

- Actual text = lives in your compiled program (or points to someone else's String)

- You're borrowing it = you can read it, but you don't own it

Let's Watch the Stack in Action!

Here's an example showing how the stack builds up and comes down as functions are called.

The diagrams will be online after class but there's space on your paper to draw them yourselves as we go.

fn main() { let x = 42; // Stack variable let name = "Alice".to_string(); // Stack + Heap let result = process_data(x, &name); println!("{}", result); } fn process_data(num: i32, text: &str) -> String { let mut doubled = num * 2; // Stack variable // A bracketed scope creates its own mini-stack frame! { let temp_multiplier = 10; // New scope variable let temp_result = doubled * temp_multiplier; // Another scope variable println!("Temp calculation: {}", temp_result); doubled = doubled + 1; // Modify outer variable } // temp_multiplier and temp_result are destroyed here! let greeting = format!("Hello {}, your number is {}", text, doubled); greeting // Return String (heap data) }

Step 1: main() starts

Stack: Heap:

┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┐

│ main(): │ │ 'A' │ 'l' │ 'i' │ 'c' │ 'e' │

│ ├ result: ??? │ └─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┘

│ ├ name: String │ ▲

│ │ ptr ────────┼───────────────────┘

│ │ len: 5 │

│ │ cap: 5 │

│ └ x: 42 │

└─────────────────┘

Step 2: Call process_data(x, &name)

Stack: Heap:

┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┐

│ process_data(): │ │ 'A' │ 'l' │ 'i' │ 'c' │ 'e' │

│ ├ doubled: 84 │ └─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┘

│ ├ text: &str │ ▲ ▲

│ │ ptr ────────┼───────────────────┘ |

│ │ len: 5 │ |

│ └ num: 42 │ |

├─────────────────┤ |

│ main(): │ |

│ ├ result: ??? │ |

│ ├ name: String ─┼───────────────────────┘

│ └ x: 42 │

└─────────────────┘

Step 3: Enter the bracketed scope {}

Stack: Heap:

┌─────────────────┐

│ { scope }: │

│ ├temp_result: 840

│ └temp_multiplier:10

├─────────────────┤ ┌─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┐

│ process_data(): │ │ 'A' │ 'l' │ 'i' │ 'c' │ 'e' │

│ ├ doubled: 85 │ <-modified └─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┘

│ ├ text: &str │ ▲ ▲

│ │ ptr ────────┼───────────────────┘ |

│ │ len: 5 │ |

│ └ num: 42 │ |

├─────────────────┤ |

│ main(): │ |

│ ├ result: ??? │ |

│ ├ name: String ─┼───────────────────────┘

│ └ x: 42 │

└─────────────────┘

Step 4: Exit the bracketed scope

Stack: Heap:

┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬──────┬──────┐

│ process_data(): │ │ 'H' │ 'e' │ 'l' │ 'l' │ 'o' │ ' ' │ 'A' │ ...

│ └ greeting: │ └─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴──────┴──────┘

│ String │ ▲

│ ptr ────────┼──────────────────────────────────┘

│ len: 28 │ ┌─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┐

│ cap: 28 │ │ 'A' │ 'l' │ 'i' │ 'c' │ 'e' │

│ ├ doubled: 85 │← Still 85! └─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┘

│ ├ text: &str │ ▲ ▲

│ │ ptr ────────┼───────────────────┘ |

│ │ len: 5 │ |

│ └ num: 42 │ |

├─────────────────┤ |

│ main(): │ |

│ ├ result: ??? │ |

│ ├ name: String ─┼───────────────────────┘

│ └ x: 42 │

└─────────────────┘

Step 5: process_data() returns

Stack: Heap:

┌─────────────────┐

│ main(): │ ┌─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬──────┬──────┐

│ │ len: 5 │ │ 'H' │ 'e' │ 'l' │ 'l' │ 'o' │ ' ' │ 'A' │ ...

│ │ cap: 5 │ └─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴──────┴──────┘

│ └ result: │ ▲

│ String │ │

│ ptr ────────┼──────────┘ ┌─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┬─────┐

│ len: 28 │ │ 'A' │ 'l' │ 'i' │ 'c' │ 'e' │

│ cap: 28 │ └─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┴─────┘

│ ├ name: String ─┼───────────────────────┘

│ ├ x: 42 │

└─────────────────┘

Step 6: main() ends

Stack: Heap:

┌─────────┐ ┌─────────────┐

│ (empty) │ │ (cleaned up │

└─────────┘ │ by Rust!) │

└─────────────┘

Take-aways from this example

- Stack builds up as functions are called, shrinks as they return

- Bracketed scopes

{}create mini-stack frames within functions - Variables in scopes are destroyed when the scope ends, but changes to outer variables persist (you can think about what that means for shadowing...)

- Heap data can outlive the function that created it (when moved/returned)

- Rust automatically cleans up heap data when no one owns it anymore