Welcome to DS210 B1 (Fall 2025)!

About this site

This site contains a complete set of resources and links for DS210 B1 for Fall 2025.

How the material works

Before lecture

- Ahead of each lecture, check the schedule for the reading associated with the next lecture and read it over (we will be moving quickly through the "lecture" part of each class so pre-reading is key).

- Complete the pre-lecture task on Gradescope - typically a quick question about the reading and/or a feedback question about the course.

During lecture

- In lecture, since we will be screens-closed for the first half each day, I will provide paper copies of key content for you to take notes on.

- In-class activities will be either paper/pencil, on gradescope, or on github classroom (URL TBD) depending on the day, and resources for those will be on this site as well.

After lecture

- A condensed version of the slides will be available on this site after the lecture under Lecture Notes.

- Homework assignments will be announced on Piazza and linked to the schedule when they are released. Due dates can be found in the schedule.

- Exam dates are on the schedule. We will have a review lecture before each exam.

Quick Links

On this site

External links

CDS 210 - Fall 2025 Syllabus

Overview

This course builds on DS110 (Python for Data Science) by expanding on programming language, systems, and algorithmic concepts introduced in the prior course. The course begins by exploring the different types of programming languages and introducing students to important systems level concepts such as computer architecture, compilers, file systems, and using the command line. It then moves to introducing a high performance language (Rust) and how to use it to implement a number of fundamental CS data structures and algorithms (lists, queues, trees, graphs etc). Then it covers how to use Rust in conjunction with external libraries to perform data manipulation and analysis.

Prerequisites: CDS 110 or equivalent

Teaching Staff

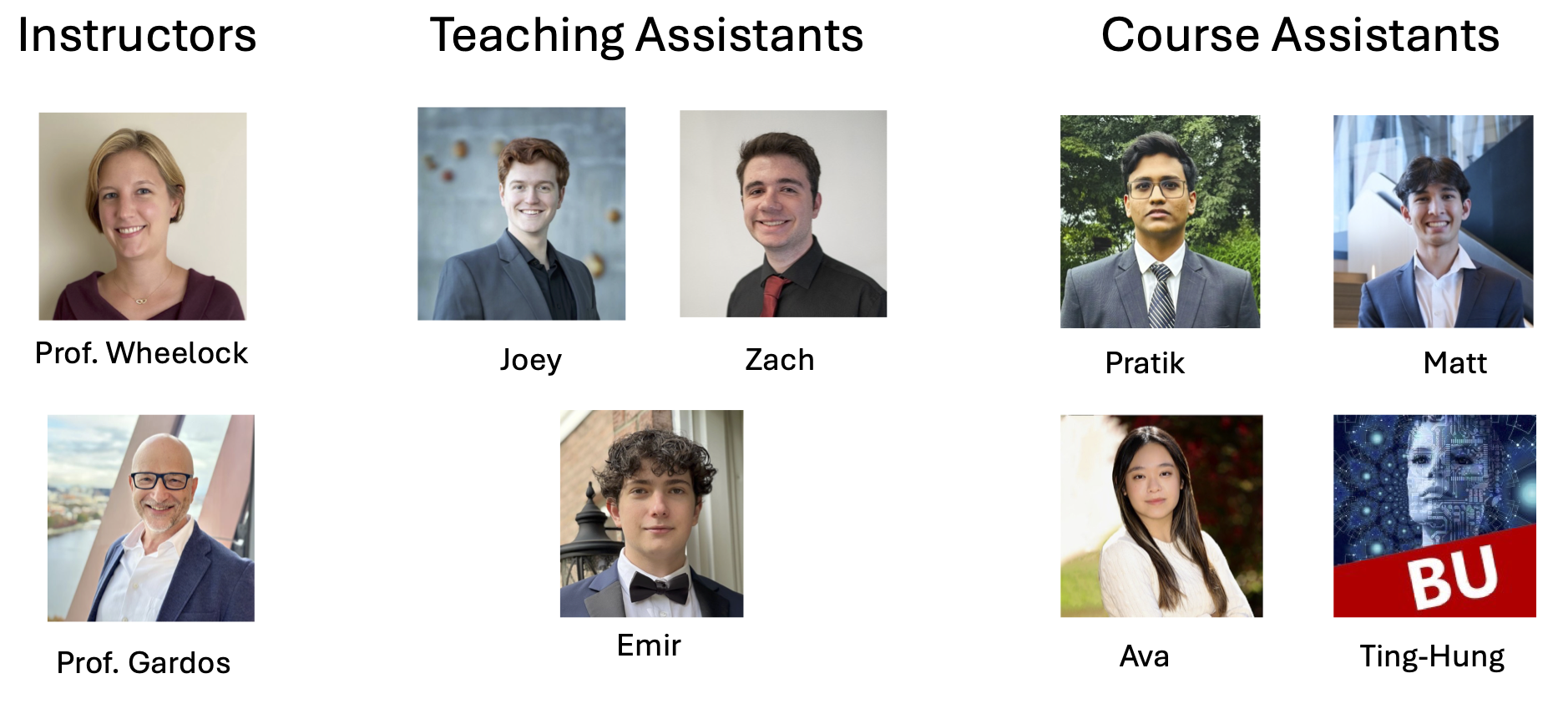

Section A1 Instructor: Thomas Gardos

Email: tgardos@bu.edu

Office hours: Tuesdays, 3:30-4:45pm @ CCDS 1623

Section B1 Instructor: Lauren Wheelock

Email: laurenbw@bu.edu

Office hours: Wed 2:30-4:00 @ CCDS 1506

Coffee slots: Fri 2:30-3:30 @ CCDS 1506

If you want to meet but cannot make office hours, send a private note on Piazza with at least 2 suggestions for times that you are available, and we will find a time to meet.

| Teaching Assistants | Course Assistants |

|---|---|

| TA: Zach Gentile Email: zgentile@bu.edu Office Hours: Mondays, 1:20-3:20pm | CA: Ting-Hung Jen Email: allen027@bu.edu Office Hours: Fridays 3:30-5:30 |

| TA: Joey Russoniello Email: jmrusso@bu.edu Office Hours: Thursdays, 10am-12 noon | CA: Matt Morris Email: mattmorr@bu.edu Office Hours: Mon/Wed 2:30-3:30 |

| TA: Emir Tali Email: etali@bu.edu Office Hours: Wednesdays, 11:30am - 1:30pm | CA: Pratik Tribhuwan Email: pratikrt@bu.edu Office Hours: Wednesdays 11:30-1:30 |

| CA: Ava Yip Email: avayip@bu.edu Office Hours: Tuesdays 3:45-5:45 |

Lectures and Discussions

A1 Lecture: Tuesdays, Thursdays 2:00pm-3:15pm (LAW AUD)

Section A Discussions (Wednesdays, 50 min):

- A2: 12:20pm – 1:10pm, SAR 300, (led by Zach)

- 3: 1:25pm – 2:15pm, IEC B10, (led by Zach)

- A4: 2:30pm – 3:20pm CGS 311, (led by Emir)

- A5: 3:35pm – 4:25pm CGS 315, (led by Emir)

B1 Lecture: Mondays, Wednesdays, Fridays 12:20pm-1:10pm (WED 130)

Section B Discussions (Fridays, 50 min):

- B2: Tue 11:00am – 11:50 (listed 12:15pm), 111 Cummington St MCS B37 (led by Joey)

- B3: Tue 12:30pm – 1:20 (listed 1:45pm), 3 Cummington Mall PRB 148 (led by Joey)

B4: Tue 2:00pm – 2:50pm (listed 3:15pm), 665 Comm Ave CDS 164B5: Tue 3:30pm – 4:20 (listed 4:45pm), 111 Cummington St MCS B31

Note: Discussion sections B4 and B5 are cancelled because of low enrollment. Please re-enroll in B2 or B3 if you were previously enrolled in B4 or B5.

Note: There are two sections of this course, they cover the same material and share a piazza and course staff but the discussion sections and grading portals are different. These are not interchangeable, you must attend the lecture and discussion sessions for your section!

Course Websites

-

Piazza

- Lecture Recordings

- Announcements and additional information

- Questions and discussions

-

Course Notes (https://ds210-fa25-private.github.io/):

- Syllabus (this document)

- Interactive lecture notes

-

Gradescope

- Homework, project, project proposal submissions

- Gradebook

-

GitHub Classroom: URL TBD

Course Content Overview

- Part 1: Foundations (command line, git) & Rust Basics (Weeks 1-3)

- Part 2: Core Rust Concepts & Data Structures (Weeks 4-5)

- Midterm 1 (~Week 5)

- Part 3: Advanced Rust & Algorithms (Weeks 6-10)

- Midterm 2 (~Week 10)

- Part 4: Data Structures and Algorithms (~Weeks 11-12)

- Part 5: Data Science & Rust in Practice (~Weeks 13-14)

- Final exam during exam week

For a complete list of modules and topics that will be kept up-to-date as we go through the term, see Lecture Schedule (MWF) and Lecture Schedule (TTH).

Course Format

Lectures will involve extensive hands-on practice. Each class includes:

- Interactive presentations of new concepts

- Small-group exercises and problem-solving activities

- Discussion and Q&A

Because of this active format, regular attendance and participation is important and counts for a significant portion of your grade (15%).

Discussions will review lecture material, provide homework support, and will adapt over the semester to the needs of the class. We will not take attendance but our TAs make this a great resource!

Pre-work will be assigned before most lectures to prepare you for in-class activities. These typically include readings plus a short ungraded quiz. We will also periodically ask for feedback and reflections on the course between lectures.

Homeworks will be assigned roughly weekly at first, and there will be longer two-week assignments later, reflecting the growing complexity of the material.

Exams Two midterms and a cumulative final exam covering theory and short hand-coding problems (which we will practice in class!)

The course emphasizes learning through practice, with opportunities for corrections and growth after receiving feedback on assignments and exams.

Course Policies

Grading Calculations

Your grade will be determined as:

- 15% homeworks (~9 assignments)

- 20% midterm 1

- 20% midterm 2

- 25% final exam

- 15% in-class activities

- 5% pre-work and surveys

I will use the standard map from numeric grades to letter grades (>=93 is A, >=90 is A-, etc). For the midterm and final, we may add a fixed number of "free" points to everyone uniformly to effectively curve the exam at our discretion - this will never result in a lower grade for anyone.

We will use gradescope to track grades over the course of the semester, which you can verify at any time and use to compute your current grade in the course for yourself.

Homeworks

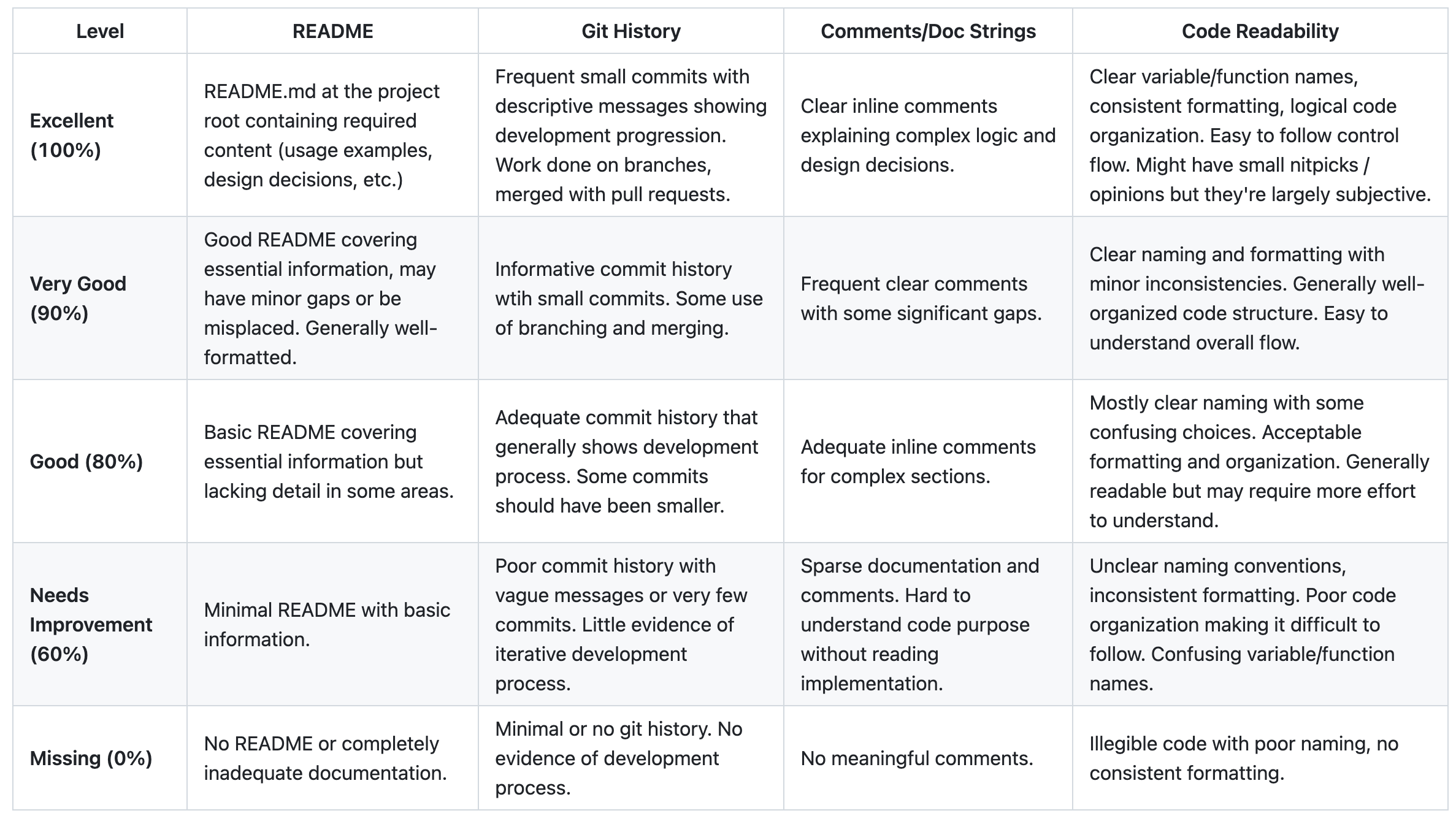

Homework assignments will be submitted by uploading them to GitHub Classroom. Since it may be possible to rely on genAI tools to do these assignments, against the course policy, our grading emphasizes development process and coding best practices in addition to technical correctness.

Typically, 1/3 of the homework score will be for correctness (computed by automated tests for coding assignments), 1/3 for documenting of your process (sufficient commit history and comments), and 1/3 for communication and best practices, which can be attained by replying to and incorporating feedback given by the CAs and TAs on your work.

Exams

The final will be during exam week, date and location TBD. The two midterms will be in class during normal lecture time.

If you have a valid conflict with a test date, you must tell me as soon as you are aware, and with a minimum of one week notice (unless there are extenuating circumstances) so we can arrange a make-up test.

If you need accommodations for exams, schedule them with the Testing Center as soon as exam dates are firm. See below for more about accommodations.

Deadlines and late work

Homeworks will be due on the date specified in gradescope/github classroom.

If your work is up to 48-hours late, you can still qualify for up to 80% credit for the assignment. After 48 hours, late work will not be accepted unless you have made prior arrangements due to extraordinary circumstances.

Collaboration

You are free to discuss problems and approaches with other students but must do your own writeup. If a significant portion of your solution is derived from someone else's work (your classmate, a website, a book, etc), you must cite that source in your writeup. You will not be penalized for using outside sources as long as you cite them appropriately.

You must also understand your solution well enough to be able to explain it if asked.

Academic honesty

You must adhere to BU's Academic Conduct Code at all times. Please be sure to read it here. In particular: cheating on an exam, passing off another student's work as your own, or plagiarism of writing or code are grounds for a grade reduction in the course and referral to BU's Academic Conduct Committee. If you have any questions about the policy, please send me a private Piazza note immediately, before taking an action that might be a violation.

AI use policy

You are allowed to use GenAI (e.g., ChatGPT, GitHub Copilot, etc) to help you understand concepts, debug your code, or generate ideas. You should understand that this may may help or impede your learning depending on how you use it.

If you use GenAI for an assignment, you must cite what you used and how you used it (for brainstorming, autocomplete, generating comments, fixing specific bugs, etc.). You must understand the solution well enough to explain it during a small group or discussion in class.

Your professor and TAs/CAs are happy to help you write and debug your own code during office hours, but we will not help you understand or debug code that generated by AI.

For more information see the CDS policy on GenAI.

Attendance and participation

Since a large component of your learning will come from in-class activities and discussions, attendance and participation are essential and account for 15% of your grade.

Attendance will be taken in lecture through Piazza polls which will open at various points during the lecture. Understanding that illness and conflicts arise, up to 4 absences are considered excused and will not affect your attendance grade.

In most lectures, there will be time for small-group exercises, either on paper or using github. To receive participation credit on these occasions, you must identify yourself on paper or in the repo along with a submission. These submissions will not be graded for accuracy, just for good-faith effort.

Occasionally, I may ask for volunteers, or I may call randomly upon students or groups to answer questions or present problems during class. You will be credited for participation.

Absences

This course follows BU's policy on religious observance. Otherwise, it is generally expected that students attend lectures and discussion sections. If you cannot attend classes for a while, please let me know as soon as possible. If you miss a lecture, please review the lecture notes and lecture recording. If I cannot teach in person, I will send a Piazza announcement with instructions.

Accommodations

If you need accommodations, let me know as soon as possible. You have the right to have your needs met, and the sooner you let me know, the sooner I can make arrangements to support you.

This course follows all BU policies regarding accommodations for students with documented disabilities. If you are a student with a disability or believe you might have a disability that requires accommodations, please contact the Office for Disability Services (ODS) at (617) 353-3658 or access@bu.edu to coordinate accommodation requests.

If you require accommodations for exams, please schedule that at the BU testing center as soon as the exam date is set.

Re-grading

You have the right to request a re-grade of any homework or test. All regrade requests must be submitted using the Gradescope interface. If you request a re-grade for a portion of an assignment, then we may review the entire assignment, not just the part in question. This may potentially result in a lower grade.

Corrections

You are welcome to submit corrections on homework assignments or the midterms. This is an opportunity to take the feedback you have received, reflect on it, and then demonstrate growth. Corrections involve submitting an updated version of the assignment or test alongside the following reflections:

- A clear explanation of the mistake

- What misconception(s) led to it

- An explanation of the correction

- What you now understand that you didn't before

After receiving grades back, you will have one week to submit corrections. You can only submit corrections on a good faith attempt at the initial submission (not to make up for a missed assignment).

Satisfying this criteria completely for any particular problem will earn you back 50% of the points you originally lost (no partial credit).

Oral re-exams (Section B only)

In Section B, we will provide you with a topic breakdown of your midterm exams into a few major topics. After receiving your midterm grade, you may choose to do an oral re-exam on one of the topics you struggled with by scheduling an appointment with Prof. Wheelock. This will involve a short (~10 minute) oral exam where you will be asked to explain concepts and write code on a whiteboard. This score will replace your original score on the topic, with a cap of 90% on that topic.

MWF Lecture, HW, and Exam Schedule

Everything in this table that occurs in the future is subject to change. Please check the readings before each lecture. Homework and exam dates should be stable - we will make a clear announcement if they need to be changed.

This table is wide so you might need to scroll to the right to see all columns.

| Date | Lecture | HW and Exams | Topic | Pre-lecture Reading | In-class Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1: Sep 1-5 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Sep 4 (Wed) | Lecture 1 | Course overview, Why Rust | Activity 1 | ||

| Sep 6 (Fri) | Lecture 2 | Hello Shell | Activity 2 | ||

| Week 2: Sep 8-12 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Sep 8 (Mon) | Lecture 3 | HW1 Out (shell, git) | Hello Git | Activity 3 | |

| Sep 10 (Wed) | Lecture 4 | Hello Rust | Ch 1: Getting Started | Activity 4 | |

| Sep 12 (Fri) | Lecture 5 | Guessing game | Ch 2 - STOP AT "Generating a Secret Number" | Activity 5 | |

| Week 3: Sep 15-19 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Sep 15 (Mon) | Lecture 6 | HW1 Due HW2 Out (rust basics) | Hello VSCode and GH Classroom | Ch 2 - the rest | Activity 6 |

| Sep 17 (Wed) | Lecture 7 | Variables and types | Ch 3.1: Variables and Mutability, Ch 3.2: Data Types | Activity 7 | |

| Sep 19 (Fri) | Lecture 8 | Functions | Ch 3.3: Functions | Activity 8 | |

| Week 4: Sep 22-26 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Sep 22 (Mon) | Lecture 9 | Control Flow | Ch 3.5: Control Flow | Activity 9 | |

| Sep 24 (Wed) | Lecture 10 | HW2 Due HW3 Out (enums, match) | Enums, match | 3 short readngs - Rust by example: Enums Ch 6.1 STARTING FROM "The Option Enum" Ch 6.2 STOP AT "How Matches Interact..." | Activity 10 |

| Sep 26 (Fri) | Lecture 11 | Error handling | Ch 9: Error Handling (through about half of 9.2) | Activity 11 | |

| Week 5: Sep 29-Oct 3 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Sep 29 (Mon) | Lecture 12 | Review Part 1 | Rust by Example | Activity 12 | |

| Oct 1 (Wed) | Lecture 13 | Review Part 2 | (Review Lecture Notes) | Activity 13 | |

| Oct 2 (Thu) | HW3 Due | ||||

| Oct 3 (Fri) | Midterm 1 | 📚 Midterm 1 📚 | |||

| Week 6: Oct 6-10 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

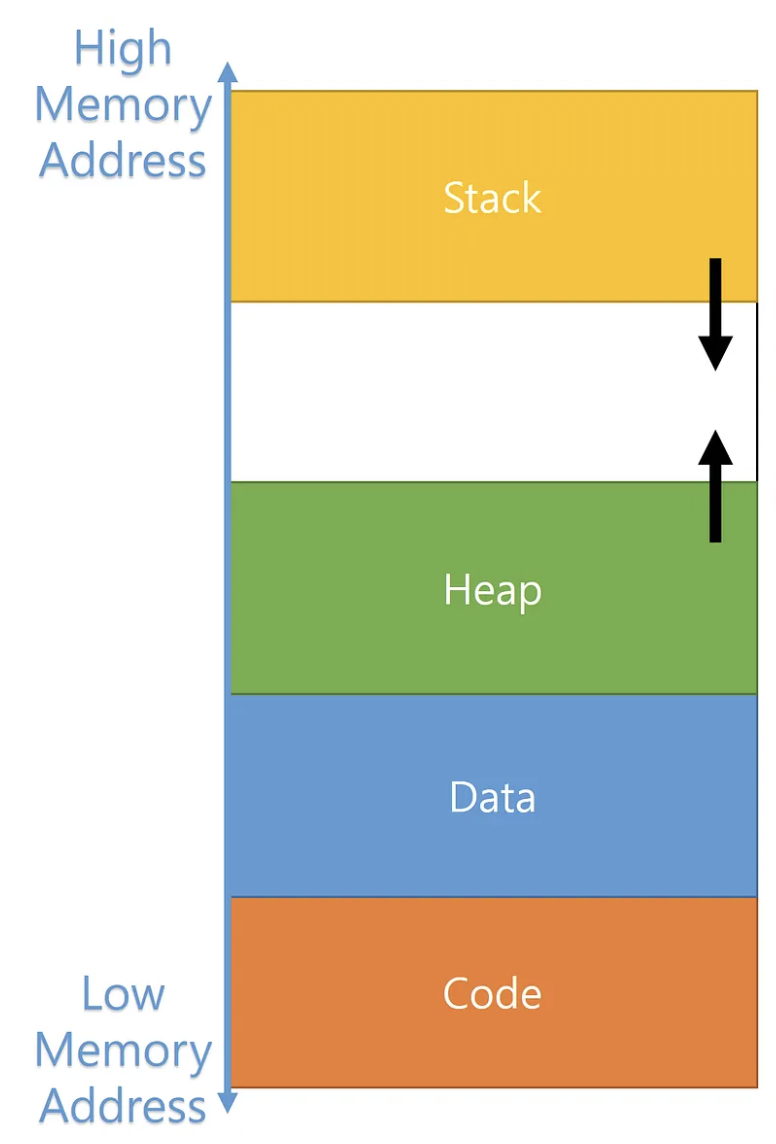

| Oct 6 (Mon) | Lecture 14 | Stack & Heap | |||

| Oct 8 (Wed) | Lecture 15 | Ownership & Vectors | Youtube video on ownership | ||

| Oct 10 (Fri) | Lecture 16 | HW4 Out | Borrowing & References | Ch 4.1: Intro to Ownership | |

| Week 7: Oct 13-17 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Oct 13 (Mon) | No Class (holiday) | ||||

| Oct 14 (Tue) | Lecture 17 Monday Schedule | &mut and the Borrow Checker | Ch 4.2: References and Borrowing | ||

| Oct 15 (Wed) | Lecture 18 | Strings & Slices | Ch 8.2: Storing UTF-8 Encoded Text with Strings | ||

| Oct 17 (Fri) | Lecture 19 | Collections & Heap Data | |||

| Week 8: Oct 20-24 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Oct 20 (Mon) | Lecture 20 | Structs & Methods | Ch 5.1: Defining and Instantiating Structs, Ch 5.3: Method Syntax | ||

| Oct 22 (Wed) | Lecture 21 | Matching structs & Review | |||

| Oct 24 (Fri) | Lecture 22 | HW4 Due HW5 Out | Generics & Type Systems | Ch 10.1: Generic Data Types | |

| Week 9: Oct 27-31 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Oct 27 (Mon) | Lecture 23 | Traits | Ch 10.2: Traits | ||

| Oct 29 (Wed) | Lecture 24 | Lifetimes | Ch 10.3: Validating References with Lifetimes (intro) | ||

| Oct 31 (Fri) | Lecture 25 | Systems Programming | None | ||

| Week 10: Nov 3-7 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Nov 3 (Mon) | Lecture 26 | Midterm Review | (Review Lecture Notes) | ||

| Nov 5 (Wed) | Midterm 2 | 📚 Midterm 2 📚 | |||

| Nov 7 (Fri) | Lecture 27 | HW5 Due HW6 Out | Packages, Crates, and Modules | Ch 7.1: Packages and Crates | |

| Week 11: Nov 10-14 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Nov 10 (Mon) | Lecture 28 | Tests and Python Integration | Ch 11.1: Writing Tests | ||

| Nov 12 (Wed) | Lecture 29 | Iterators & Closures | Ch 13.1: Closures, Ch 13.2: Processing a Series of Items with Iterators | ||

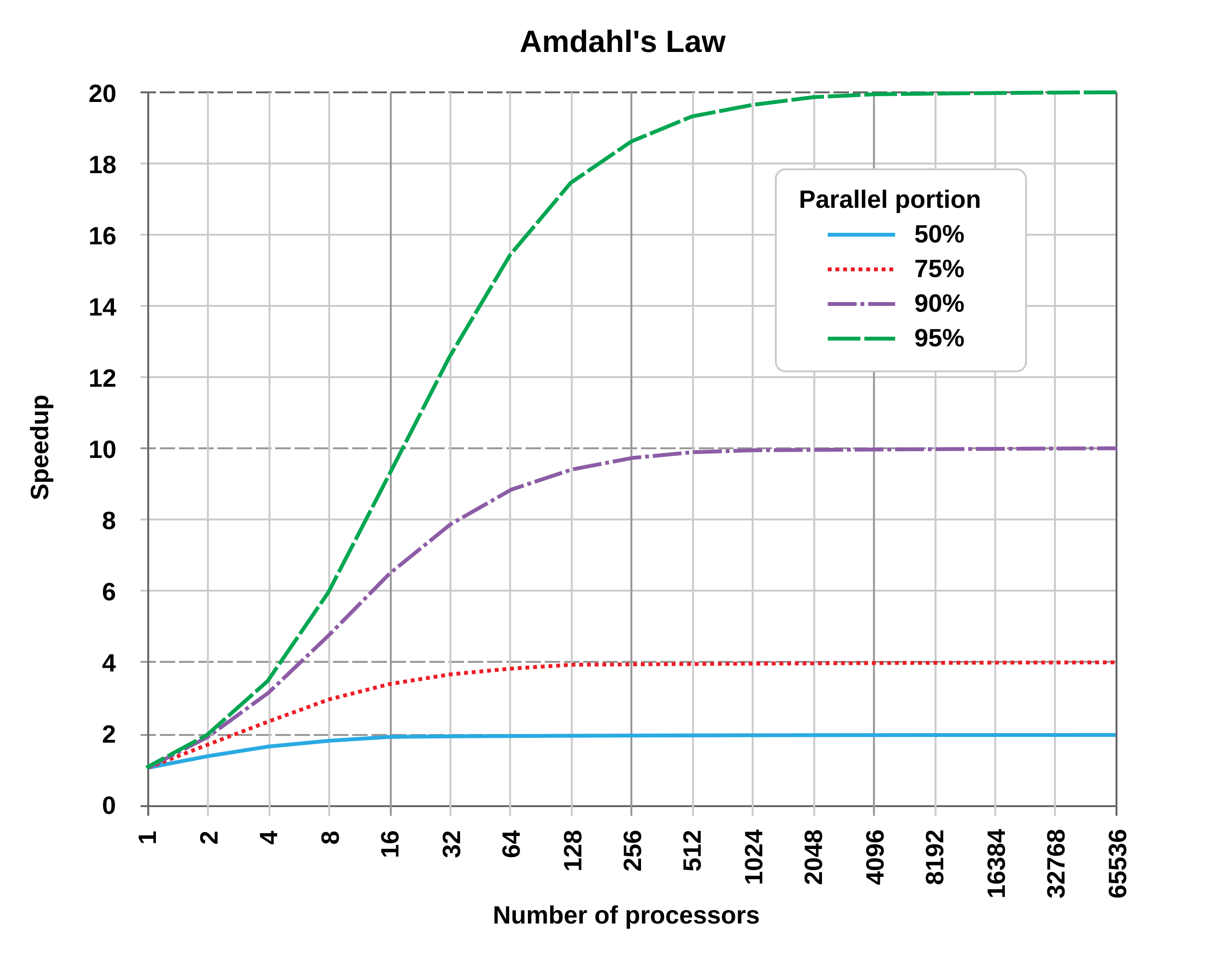

| Nov 14 (Fri) | Lecture 30 | File I/O, Concurrency Overview, Scientific Computing | Ch 12.2: Reading a File, Ch 16: Fearless Concurrency (intro) | ||

| Week 12: Nov 17-21 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Nov 17 (Mon) | Lecture 31 | Big O Notation & Algorithmic Complexity | Algorithms Complexity (MIT OpenCourseWare), Big-O Notation (Python DS Ch 2) | ||

| Nov 19 (Wed) | Lecture 32 | Algorithm Design: Comparing Sorting Algorithms | Sorting and Searching (Python DS Ch 5: Merge Sort, Quick Sort), Sorting Algorithms | ||

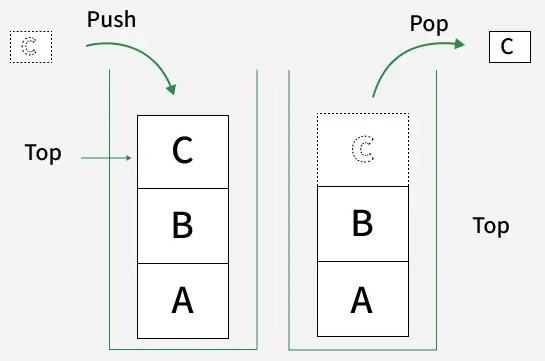

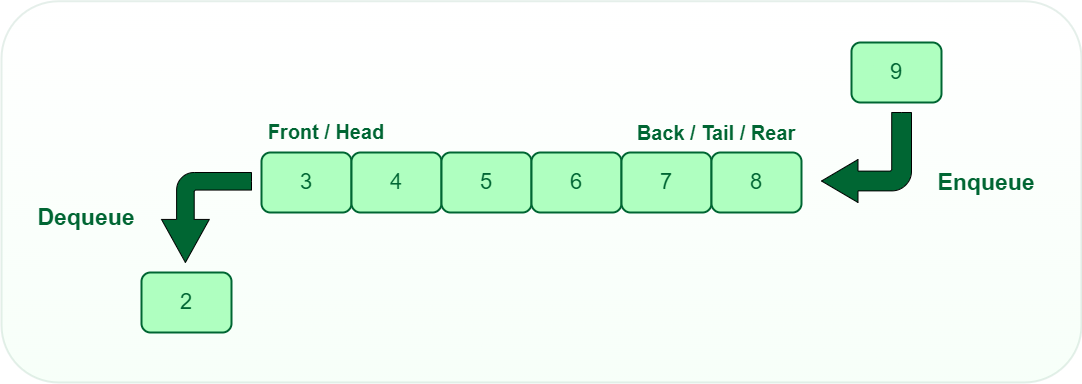

| Nov 21 (Fri) | Lecture 33 | HW6 Due HW7 Out | Linear Data Structures | Basic Data Structures (Python DS Ch 3: Stacks, Queues, Deques), Stack & Queue in Rust | |

| Week 13: Nov 24-28 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Nov 24 (Mon) | Lecture 34 | Priority Queues & Heaps | Binary Heaps (Python DS Ch 6: Binary Heaps), Heap Data Structure (HackerRank) | ||

| Nov 26 (Wed) | No Class (Thanksgiving) | ||||

| Week 14: Dec 1-5 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Dec 1 (Mon) | Lecture 35 | Trees & Binary Search Trees | Trees and Tree Algorithms (Python DS Ch 6: Trees, BST), Tree Traversals Visualized | ||

| Dec 3 (Wed) | Lecture 36 | Graph Representation & Traversals | Graphs Introduction (Python DS Ch 7: Graph Intro, BFS, DFS), Graph Theory Intro, BFS & DFS Algorithms (William Fiset) | ||

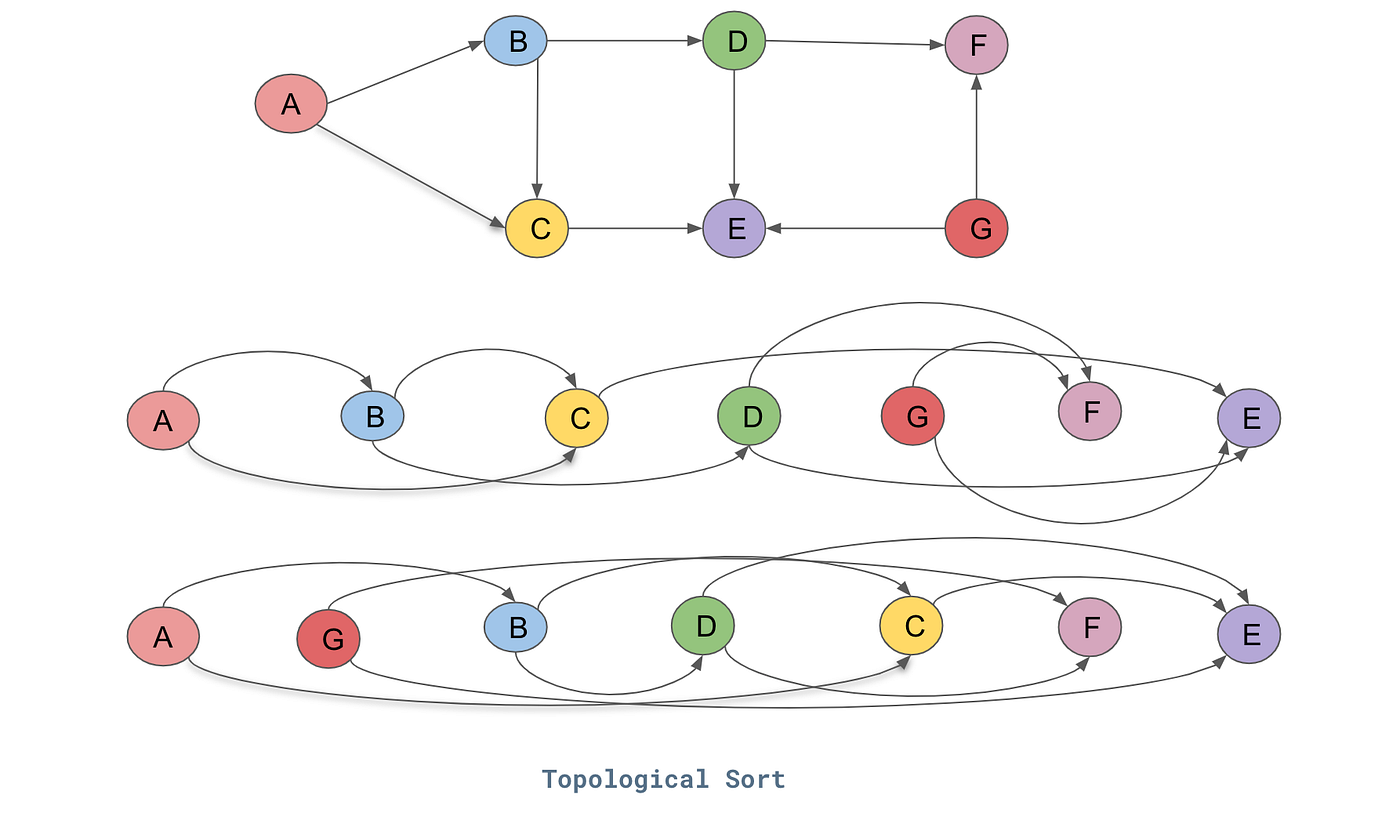

| Dec 5 (Fri) | Lecture 37 | HW7 Due | Advanced Graph Algorithms (Topological Sort and MST) | Graph Algorithms (Python DS Ch 7: Advanced topics) | |

| Week 15: Dec 8-12 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Dec 8 (Mon) | Lecture 38 | Shortest Paths & Dijkstra's Algorithm | Shortest Path Problems (Python DS Ch 7: Dijkstra), Dijkstra's Algorithm (Computerphile) | ||

| Dec 10 (Wed) | Final Review | Last Day of Classes | |||

| Finals Week | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| TBD | 📚 Final Exam 📚 |

Lecture 1 - Welcome to DS210! (Section B)

What today will look like

- Screen-free space

Agenda

- What is this course?

- Quick introductions and logistics

- Syllabus review activity

- AI use discussion

All the material in the course will be in the service of at least one of:

- Code development skills - tools, collaboration, best practices

- Programming in Rust

- Systems programming (memory, performance, types)

- Data structures and algorithms (to be continued in DS 320)

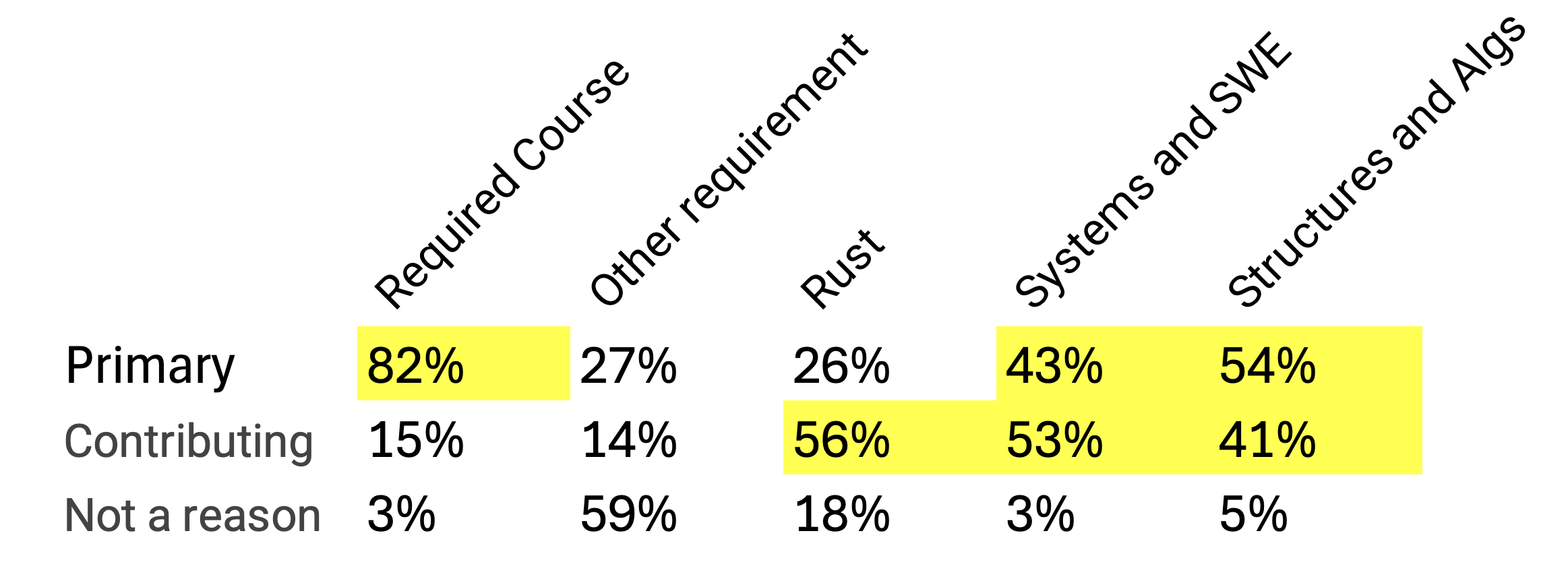

But why are YOU taking it?

I just want to say - I hear you. Here's my job...

Why coding development skills matter

- Often never taught explicitly, can be tricky to self-teach

- Vitally important in "the real world", when you'll need to:

- Get out of a "detached head" state without losing your head

- Collaborate with others on code across space and time

- Work on massive codebases and data warehouses

Why Systems Programming Matters

Knowing enough to answer

- Why is my code slow?

- Why is my app crashing?

- Why did we get hacked?

Or better yet... not having to answer those questions as often!

Why data structures and algorithms?

Knowing enough to answer

- Why is my model producing weird results?

- Is there a smarter way to do this than brute-force?

- How is this ever going to scale?

And inventing whole net new ways of working with data.

Also -

- Technical interviews

- Intellectual joy

Why are we doing this in Rust?

- A second language

- A compiled language

- A systems programming language

- A modern language

- An increasingly popular language

Logistics

What have you heard about the course?

New This Semester

- Local dev and focus on development skills

- Mastery vs coverage

- In-class activities in every lecture

- Better alignment between lectures, homeworks, and exams

- Three exams, no final project

Why the shift to "active learning"?

- A meta-analysis of 225 studies found students in traditional lecture courses are 1.5 times more likely to fail compared to active learning environments.

- Active learning produces consistent effect sizes of 0.47-0.49 standard deviations, or half a letter grade improvement.

- Active learning reduces achievement gaps between underrepresented and majority students by 33-45%.

Our Teaching Staff

Two things to know about me...

- I am your advocate.

- It's us against the material

- No gotchas

- Lots of practice and review in class

- Please share feedback

- I want to know who you are (coffee slots!)

- If you are struggling, please reach out early so we can help

- I have high expectations for you.

- Grading on an absolute scale

- Less weight on homeworks, more on exams

- When you're here, you're HERE

- You CAN learn this stuff!

What this means for grading

35% course grade based on EFFORT:

- 15% homeworks

- 15% in-class activities

- 5% pre-work and surveys

65% based on MASTERY:

- 20% midterm 1

- 20% midterm 2

- 25% final exam

Lectures and Discussions

Lecture: Mondays, Wednesdays, Fridays 12:20pm-1:10pm (WED 130)

Discussion B2 - led by Joey

- Tue 11:00am – 11:50 (listed 12:15pm)

- 111 Cummington St MCS B37

Discussion B3 - led by Joey

- Tue 12:30pm – 1:20 (listed 1:45pm)

- 3 Cummington Mall PRB 148

B4 and B5 are cancelled this semester

About Section A

Section A Instructor: Thomas Gardos

- Email: tgardos@bu.edu

- Office hours: Tuesdays, 3:30-4:45pm @ CCDS 1623

Their schedule:

- Lectures are Tue / Thu 2-3:15

- Discussions are Wednesday afternoons

- Pacing may be different, so please attend B lectures and discussions!

What we share:

- Homework assignments and due dates

- Exams topics (different questions) and rough dates

- TAs and CAs

Thanks for hanging tight as we get set up!

Syllabus Review Activity (20 min)

Instructions

In groups of 2-3, spend 15 minutes answering the worksheet questions on paper.

Recap

AI use discussion (20 min)

Instructions

Think-pair-share style, each ~6-7 minutes, with wrap-up.

Form groups of 2-3 (different groups if possible!).

We're not putting this on gradescope (sorry if you filled this out on gradescope yesterday! 😅)

Round 1: Learning Impact

How might GenAI tools help your learning in this course?

How might they get in the way?

Round 2: Values & Fairness

What expectations do you have for how other students in this course will or won't use GenAI?

What expectations do you have for the teaching team so we can assess your learning fairly given easy access to these tools?

Round 3: Real Decisions

Picture yourself stuck on a challenging Rust problem at midnight with a deadline looming.

What options do you have?

What would help you make decisions you'd feel good about?

Wrap-up

By Friday

Please fill out the intro survey linked in the email and mark it complete on Gradescope.

Quick show of hands - mac/linux vs windows?

Bring your laptop and come prepared to work with the shell next class!

Lecture 2 - Hello Shell!

Intro

And the survey says...

- Cold calling

- High weight on exams, no curve

- Rust :-P

- Office hour availability

- Cancelling the project

- Regrading and corrections

- 4 "free" absenses

- AI / collaboration policy

- Late policy

- Course content changes

- Coffee slots :-)

- Oral re-exams

- No curve / grade quotas

- Homework grading approach

- Participation credit

Some FAQs

Common questions

- Exam format and content

- How I learned your names

- Where are recordings / lecture notes

- Partial credit / extra credit

- How bad til exams get a curve?

Some more points to note

- Gradescope vs GitHub Classroom

- Lecture notes for A vs B

I promise to revisit these Monday:

- Prework

- Homework and exam schedule

Motivation

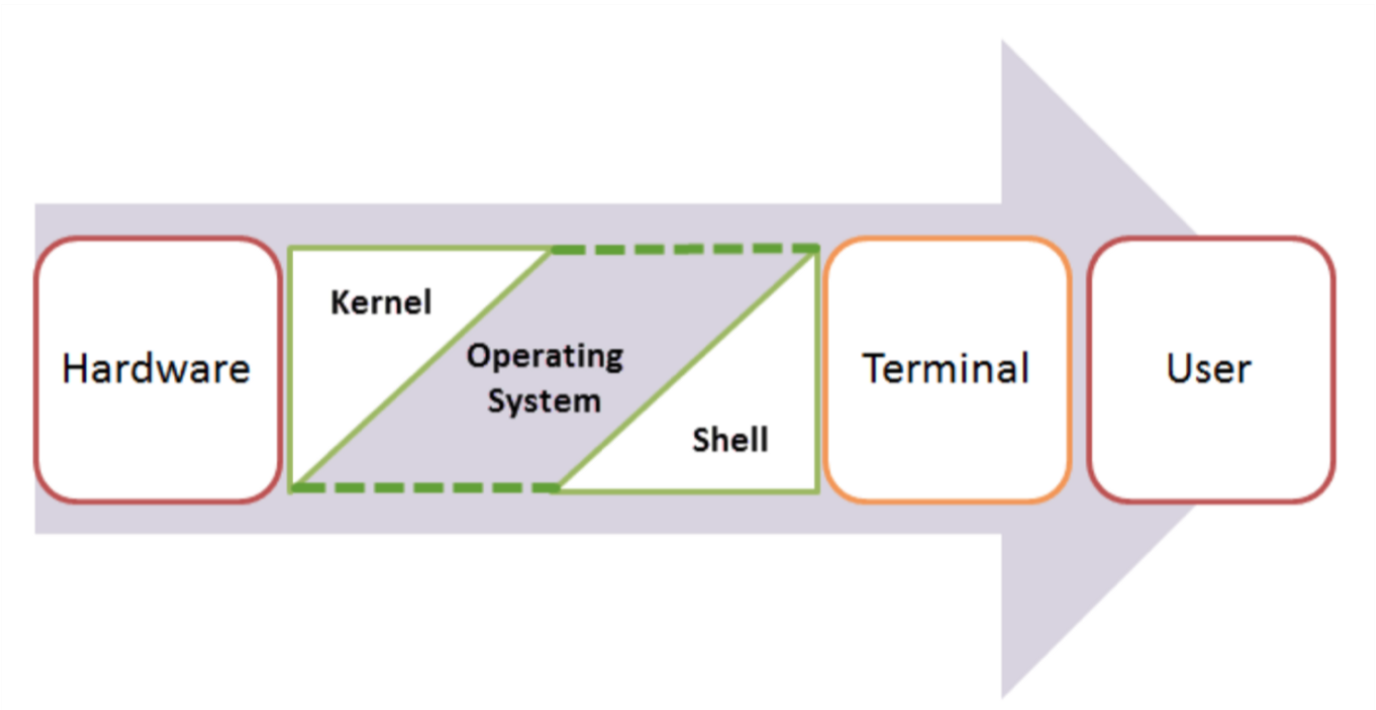

What is the terminal?

What is the terminal?

... the kitchem metaphor

Shell, Terminal, Console, Command line... and what's Bash?

- The command line is the interface where you type commands to interact with your computer.

- The command prompt is the character(s) before your cursor that signals you can type and can be configured with other reminders.

- The terminal or console is the program that opens a window and lets you interact with the shell.

- The shell is the command line interpreter that processes your commands. (You might also encounter "a command line" in text-based games)

Terminals are more like applications and shells are more like languages.

Shell, Terminal, Console, Command line... and what's Bash?

Terminals come in proper nouns:

- Terminal (macOS)

- iTerm2 (macOS)

- GNOME Terminal (Linux)

- Konsole (Linux)

- Command Prompt (Windows)

- PowerShell (Windows)

- Git Bash (Windows)

Shells also come in proper nouns:

- Bash (Bourne Again SHell) - most common on Linux and macOS

- Zsh (Z Shell) - default on modern macOS

- Fish (Friendly Interactive SHell) - user-friendly alternative

- Tcsh (TENEX C Shell) - popular on some Unix systems

- PowerShell - advanced shell for Windows

Shell, Terminal, Console, Command line... and what's Bash?

BUT they are often used interchangeably in speech:

- "Open your terminal"

- "Type this command in the shell"

- "Run this in the command line"

- "Execute this in your console"

What is this all good for?

Lightning fast navigation and action

# Quick file operations

ls *.rs # Find all Rust files

grep "TODO" src/*.rs # Search for TODO comments across files

wc -l data/*.csv # Count lines in all CSV files

- How would you to this "manually"?

It's how we're going to build and manage our rust projects

# Start your day

git pull # Get latest team changes

cargo test # Make sure everything still works

# ... code some features ...

cargo run # Test your new feature

git add src/main.rs # Stage your changes

git commit -m "Add awesome feature" # Save your work

git push # Share with the team

For when your UI just won't cut it

- Confused by "invisible files" and folders?

ls -la

For when your UI just won't cut it

- Need to find a file where you wrote something a while ago

grep -r "that thing I wrote 6 months ago"

- Modify lots of files at once

# Rename 500 photos at once

for file in *.jpg; do mv "$file" "vacation_$file"; done

# Delete all files older than 30 days

find . -type f -mtime +30 -delete

- "Why is my computer fan running like it's about to take off?"

df -h # See disk space usage immediately

ps aux | grep app # Find that app that's hogging memory

top # Live system monitor

In other words, the command line provides:

- Speed: Much faster for repetitive tasks

- Precision: Exact control over file operations

- Automation: Commands can be scripted and repeated

- Remote work: Essential for server management

- Development workflow: Many programming tools use command-line interfaces

Learning objectives for today (TC 12:30)

By the end of this lecture, you should be able to:

- Navigate your file system on the command line

- Create, copy, move, and delete files and directories at the command line

- Interpret file permissions

- Use pipes and redirection for basic text processing

We will also discuss, but you are not responsible for:

- Customizing your shell profile with aliases and functions

- Writing simple shell scripts

![]() We'll have one of these slides every lecture and it's a great way to check in on what material you're responsible for for exams!

We'll have one of these slides every lecture and it's a great way to check in on what material you're responsible for for exams!

The file system and navigation

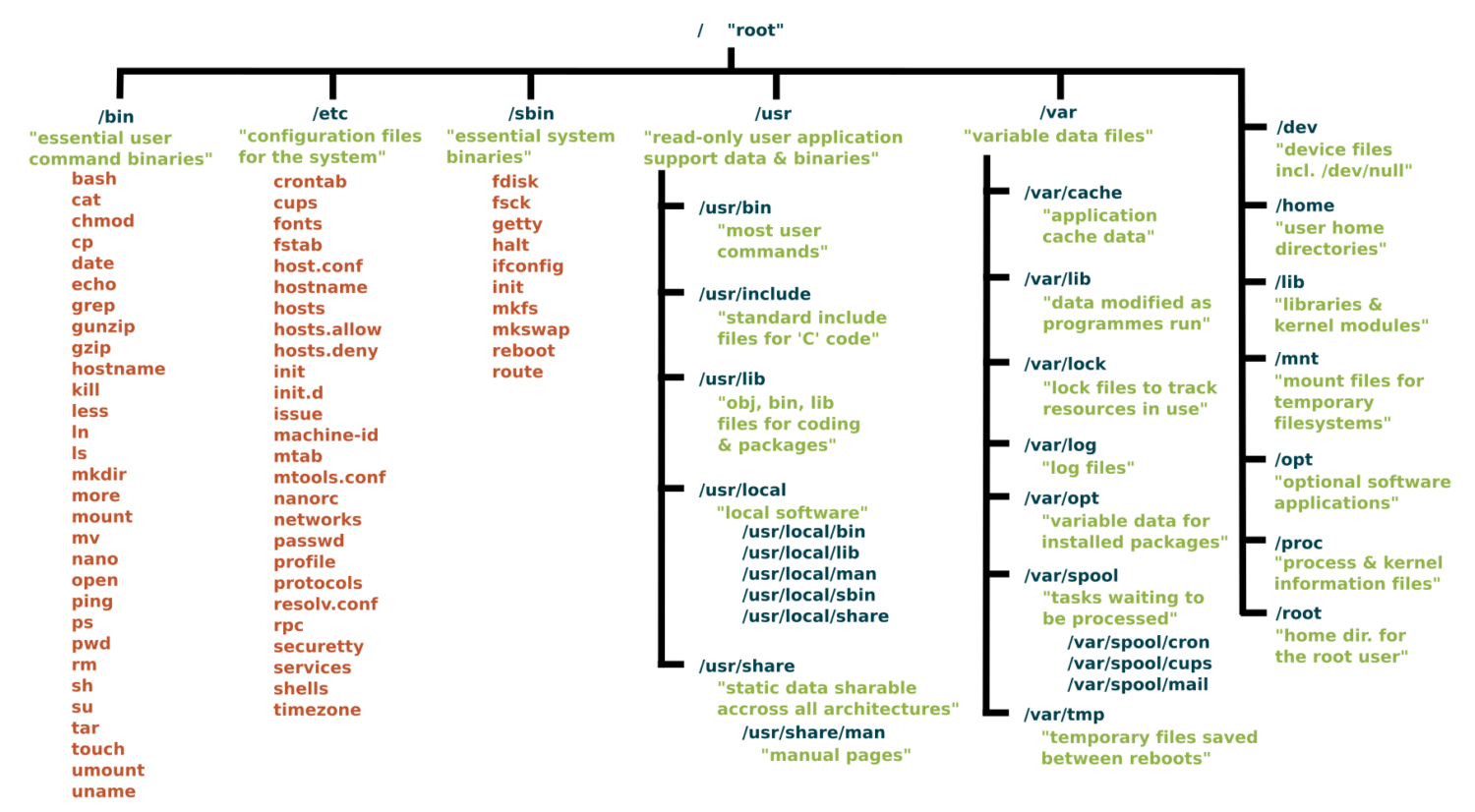

Everything starts at the root

Root Directory (/):

In Linux, the slash character represents the root of the entire file system.

(On a Windows machine you might see "C:" but on Linux and MacOS it is just "/".)

(We'll talk more about Windows in a minute)

Key Directories You'll Use:

/ # Root of entire system

├── home/ # User home directories

│ └── username/ # Your personal space

├── usr/ # User programs and libraries

│ ├── bin/ # User programs (like cargo, rustc)

│ └── local/ # Locally installed software

└── tmp/ # Temporary files

Navigation Shortcuts:

~= Your home directory.= Current directory..= Parent directory/= Root directory

Let's take a look / basic navigation demo

Demo time! First let's look at the command prompt...

Maybe half of your interactions with the shell will look like:

pwd # Print working directory

ls # List files in current directory

ls -a # List files including hidden files

ls -al # List files with details and hidden files

cd directory_name # Change to directory

cd .. # Go up one directory

cd ~ # Go to home directory

Tips:

- Use

Tabfor auto-completion (great for paths!) - Use

Up Arrowto access command history - Try

control-cto abort something running or clear a line - You can't click into a line to edit it, use left/right arrows (or vim, or copy-paste)

What's going on here?

The command line takes commands and arguments.

ls -la ~

The grammer is like a command in English: VERB (NOUN) ("eat", "drink water", "open door")

ls is the command, -la and ~ are arguments.

Flags / Options

Special arguemnts called "options" or "flags" usually start with a dash - and can be separate or combined. These are equivalent:

ls -la

ls -al

ls -a -l

ls -l -a

BUT they typically need to come before other arguemnts:

ls -l -a ~ # works!

ls -l ~ -a # does not work

Let's pause for the elephant in the room

- macOS is built on Unix

- Windows is entirely different

dirinstead oflscopyandmoveinstead ofcpandmv

- We strongly recommend Windows users install a terminal with

bash(we'll do it today!) so we can speak the same language.

One thing is unavoidable: different paths

/vsC:\Users\(vote for which is a back slash!)- This incompatibility has caused more suffering than metric vs imperial units.

Essential Commands for Daily Use (TC 12:35)

Quiz time!

What do these stand for and what do they do:

pwdcdls

And

- How can you "get home quickly"?

![]() These slides make a great starting point for Anki questions!

These slides make a great starting point for Anki questions!

Reverse, reverse!

- How can you see what directory you're in?

- How can you look around to see what's in the folder?

- How can you go into one of those folders?

- How can you back out?

- How can you see hidden files?

The rest of the 80% of bash commands you will mostly ever use

Demo time!

mkdir project_name # Create directory

mkdir -p path/to/dir # Create nested directories

touch notes.txt # Create empty file

echo "Hello World" > notes.txt # Overwrite file contents

echo "It is me" >> notes.text # Append to file content

cat filename.txt # Display entire file

head filename.txt # Show first 10 lines

tail filename.txt # Show last 10 lines

less filename.txt # View file page by page (press q to quit)

nano filename.txt # Edit a file

cp file.txt backup.txt # Copy file

mv old_name new_name # Rename/move file

rm filename # Delete file

rm -r directory_name # Delete directory and contents

rm -rf directory_name # Delete dir and contents without confirmation

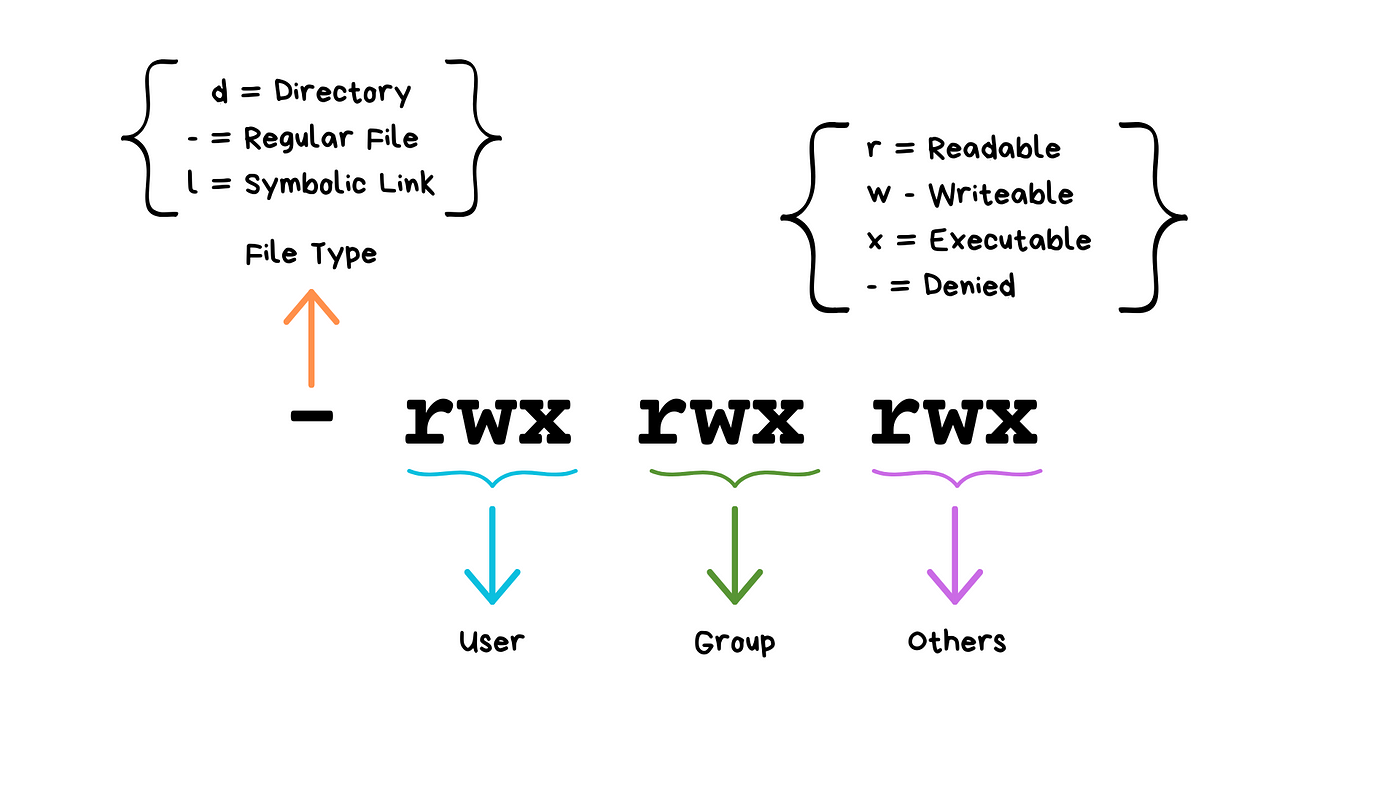

Understanding ls -la Output

-rw-r--r-- 1 user group 1024 Jan 15 10:30 filename.txt

drwxr-xr-x 2 user group 4096 Jan 15 10:25 dirname

(Don't worry about "groups"!)

We will see these kinds of permissions again in Rust programming!

Common Permission Patterns

644orrw-r--r--: Files you can edit, others can read755orrwxr-xr-x: Programs you can run, others can read/run600orrw-------: Private files only you can access

(Any guesses about the numeric codes?)

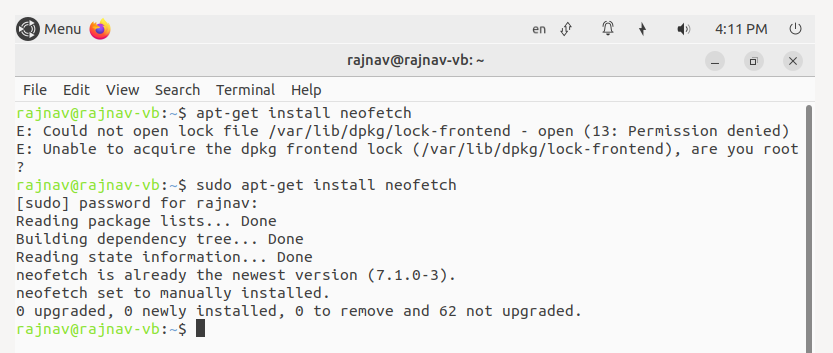

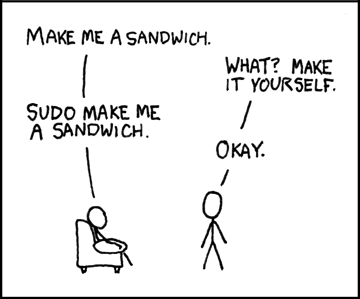

Don't have permission? Don't tell anyone I told you this but...

Don't have permission? Don't tell anyone I told you this but...

- What do you think

sudostands for?

One list thing... Combining Commands with Pipes

ls | grep ".txt" # List only .txt files

cat file.txt | head -5 # Show first 5 lines of file

ls -l | wc -l # Count number of files in directory

Combining Commands with Pipes

More Examples:

# Find large files

ls -la | sort -k5 -nr | head -10

# Count total lines in all text files

cat *.txt | wc -l

So tell me, what's the difference...

ls -la | wc -l

ls -la > results.txt

FYI (TC 12:45 or skip)

For your awareness - Your Shell Profile

Understanding Shell Configuration Files:

Your shell reads a configuration file when it starts up. This is where you can add aliases, modify your PATH, and customize your environment.

Common Configuration Files:

- macOS (zsh):

~/.zshrc - macOS (bash):

~/.bash_profileor~/.bashrc - Linux (bash):

~/.bashrc - Windows Git Bash:

~/.bash_profile

Finding Your Configuration File:

It's in your Home directory.

# Check which shell you're using (MacOS/Linus)

echo $SHELL

# macOS with zsh

echo $HOME/.zshrc

# macOS/Linux with bash

echo $HOME/.bash_profile

echo $HOME/.bashrc

Adding aliases to you shell profile

# Edit your shell configuration file (choose the right one for your system)

nano ~/.zshrc # macOS zsh

nano ~/.bash_profile # macOS bash or Git Bash

nano ~/.bashrc # Linux bash

# Add these helpful aliases:

alias ll='ls -la'

alias ..='cd ..'

alias ...='cd ../..'

alias projects='cd ~/development'

alias rust-projects='cd ~/development/rust_projects'

alias grep='grep --color=auto'

alias tree='tree -C'

# Custom functions

# This will make a directory specified as the argument and change into it

mkcd() {

mkdir -p "$1" && cd "$1"

}

Modifying your PATH

You may need to do this occasionally to make tools you install available on the command line.

# Add to your shell configuration file

export PATH="$HOME/bin:$PATH"

export PATH="$HOME/.cargo/bin:$PATH" # For Rust tools (we'll add this later)

# For development tools

export PATH="/usr/local/bin:$PATH"

Applying Changes:

# Method 1: Reload your shell configuration

source ~/.zshrc # For zsh

source ~/.bash_profile # For bash

# Method 2: Start a new terminal session

# Method 3: Run the command directly

exec $SHELL

Shell scripts

Shell script files typically use the extension *.sh, e.g. script.sh.

Shell script files start with a shebang line, #!/bin/bash.

#!/bin/bash

echo "Hello world!"

To execute shell script you can use the command:

source script.sh

Before it gets noisy in here... (TC 12:50)

- What does

drwxr-xr-xmean? - How can I quickly write "I'm awesome" to my

affirmations.txtfile? - How can I delete my

file_of_secrets.txtbefore the cops get here? - How can I rename my

file_of_secrets.txtso it "disappears"? - How can I find it again?

In-Class Activity: Shell Challenge

In groups of 2-3, go to https://github.com/lauren897/ds210-fa25-b and complete the challenge.

Remember to submit on gradescope (once per group)! (There's a grace period til 1:30)

Coming up -

- Monday: git and GitHub

- Releasing HW1 (exact dates TBD but we'll give at least a full week)

- We start Rust on Wednesday!

- Wednesday also starts pre-work, we'll explain more on Monday

- I'll post a coffee slot sign-up sheet tonight

- I'll have lecture notes / a site set up by Monday

Lecture 3 - Hello Git!

The problem with "manual" version control

- Storage space (due to redundancy)

- Hard to see what changes were made when

- Hard to collaborate (merge, review)

The collaboration problem

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lecture, you should be able to:

- Understand why version control is critical for programming

- Configure Git for first-time use

- Create repositories and make meaningful commits

- Connect local repositories to GitHub

- Use the basic Git workflow for individual projects

- Use the

gitcommandsclone,checkout,add,commit,push,pull,merge

Warning - this is a lot to take in at once, but we will be practicing and developing this ALL semester

The Four (and a half) Locations

Repository (Repo): A folder tracked by Git, containing your project and its complete history.

Workspace The files on your machine right now, where we edit them

Staging Area Temporary holding spot for changes before committing

Local repository Where we store committed changes locally

Remote repository A server (like GitHub) for storing and collaborating on code

Git workflow concepts

Commit: A snapshot of your project at a specific moment, with a message explaining what changed.

Diff: The collection of specific edits in a commit. (Or generally, the differences between any two versions of a file.)

Branch: One "timeline" of commits that may diverge from other timelines

Git Workflows

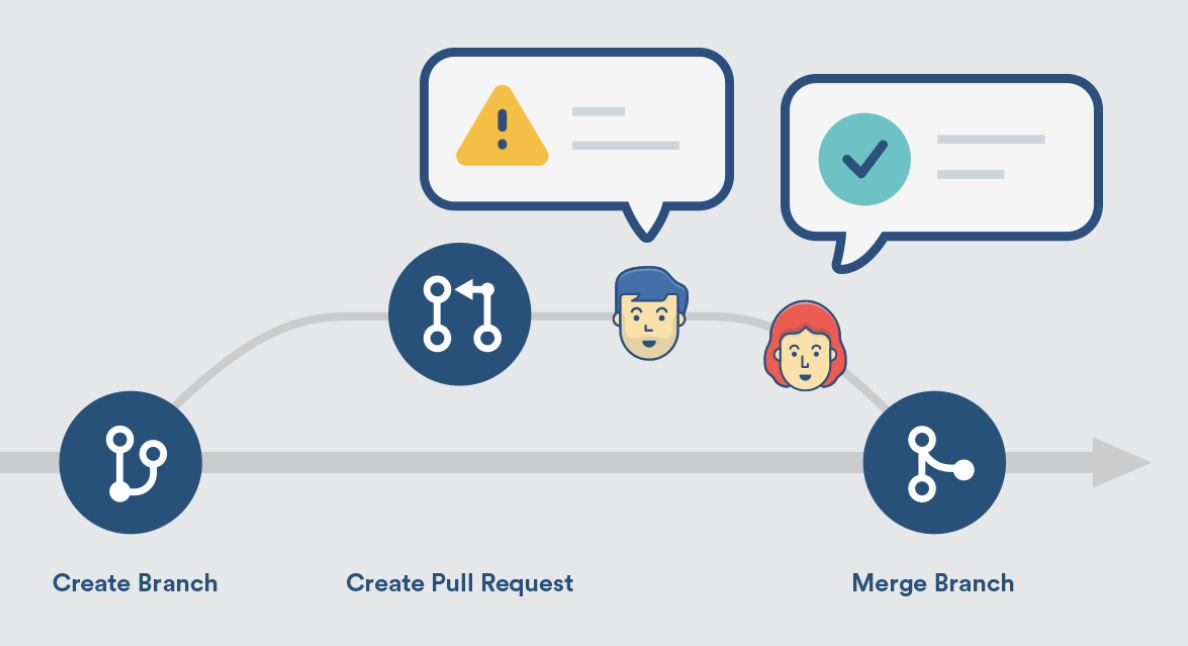

Merging and Pull Requests

Merge: Combines changes from different branches. Takes commits from one branch and integrates them into another branch.

Merge Conflict: Merging may fail if both branches change the same lines. Git will point to the conflict and ask you to resolve it before finishing the merge.

Pull Request (PR): A request to merge your changes into another branch, typically used for code review. You "request" that someone "pull" your changes into the main codebase.

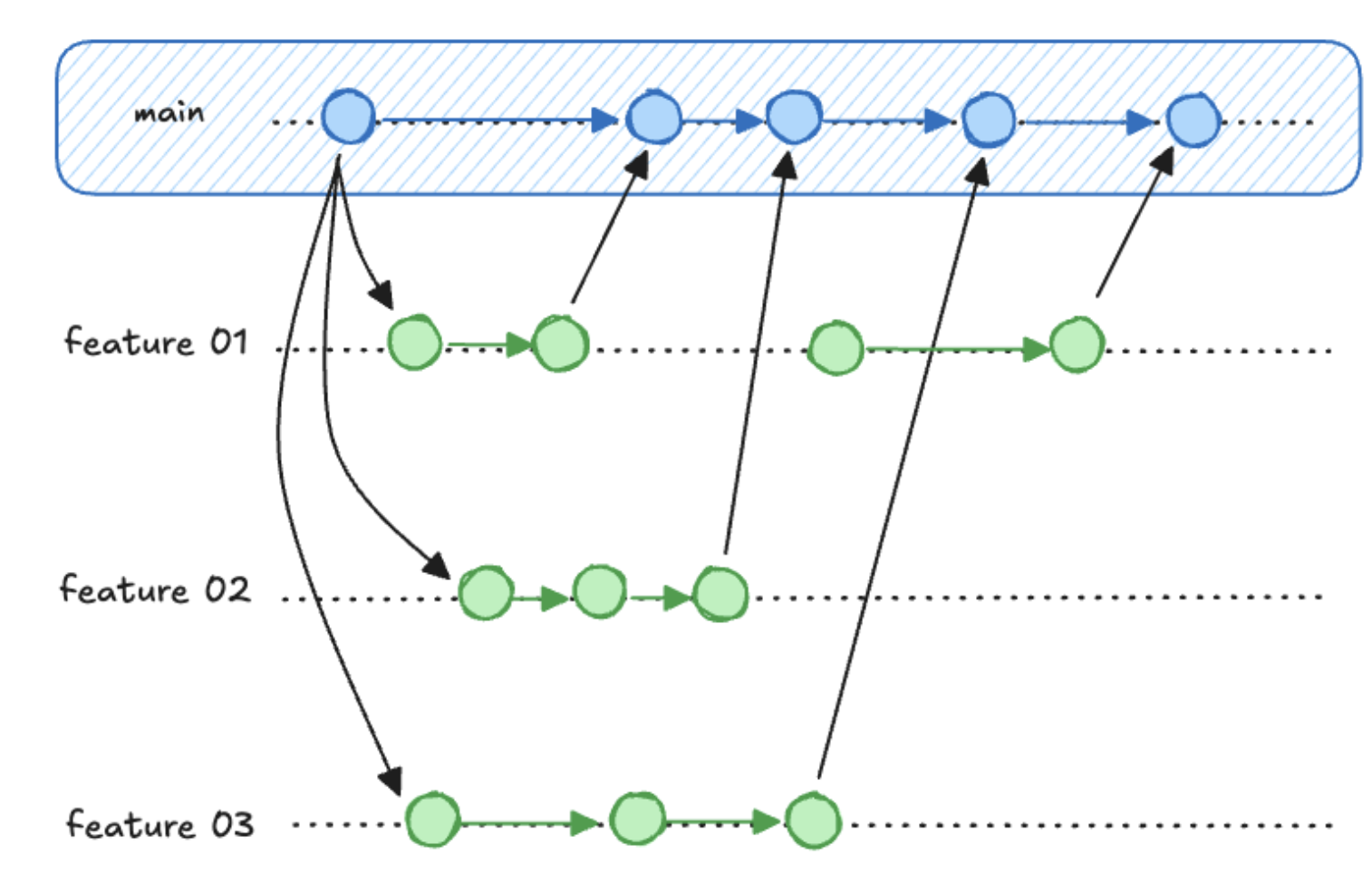

Git Branching

- Main branch: Usually called

main(ormasterin older repos) - Feature branches: Created for new features or bug fixes

- Isolates experimental work

- Enables parallel development

- Facilitates code review

Essential Git Commands

Let's take this to the command line.

One-Time Setup

# Configure your identity (use your real name and email)

git config --global user.name "Your Full Name"

git config --global user.email "your.email@example.com"

# Set default branch name

git config --global init.defaultBranch main

Note: The community has moved away from

masteras the default branch name, but it may still be default in some installations.

Starting a New Project - Demo/Practice (shout it out)

- Where am I?

- How can I move to my projects directory?

- How can I create a new project?

- How can I move into the project?

git init- What did that do?

A note about .gitignore

Anything in your repo you DON'T want tracked in git as part of you repo can go in the .gitignore file.

latexfile.aux

.ipynb_checkpoints/

.vscode

.DS_Store

/tmp

If you ever run git add and notice it added a bunch of files you don't recognize - it's time to update your .gitignore

Daily Git Workflow

# Create a descriptive branch name for the change you want to make

git checkout -b feature_branch

# Check what's changed

git status # See current state

# Stage changes for commit

git add filename.rs # Add specific file to staging

git add . # Add all changes in current directory

git commit -m "Add calculator function" # Commit with a comment

git checkout main # Switch back to main

git merge feature_branch # Merge branch back into main

# merge merges the branch you NAME *into* the branch you're currently ON

Writing Good Commit Messages

- Start with a present / imperative verb

- Be brief and specific

- If you find yourself using "and" a lot your commits are too big

The Golden Rule: Your commit message should complete this sentence: "If applied, this commit will [your message here]"

Good Examples:

git commit -m "Add input validation for calculator"

git commit -m "Fix division by zero error"

git commit -m "Refactor string parsing for clarity"

git commit -m "Add tests for edge cases"

Bad Examples:

git commit -m "fix a bug" # What bug

git commit -m "fix date range bug and added multi-user feature" # Too much at once

git commit -m "trying again" # what are you doing differently?

Working with GitHub

Why GitHub?

- Remote backup for solo work

- Easy sharing and collaboration

- Many tools and integrations

Connecting to GitHub

You CAN create a repo locally then push it to GitHub:

git init

git remote add origin https://github.com/yourusername/repository-name.git

git push -u origin main

But you can also create it from GitHub and clone it locally - what we'll usually do

# Clone existing repository

git clone https://github.com/username/repository.git

To keep things in sync your main actions are

# Get to the repository

cd repository

# Pull any changes from GitHub

git pull

# Push your commits to GitHub

git push # you'll be prompted at this point to log into github in your terminal

Git, GitHub, and shell together - Demo

# Creating a new repo

cd ~/ds210/assignments

mkdir assignment_01

cd assignment_01

git init

# Make a branch

git checkout -b problem1

# Make initial commit

touch README.md

echo "# Assignment 1" > README.md

git add README.md

git commit -m "Initial project setup for Assignment 1"

# Work and commit frequently

# ... write some code ...

mkdir src

touch src/main.rs

echo "some rust code" > src/main.rs

git add src/main.rs

git commit -m "Implement basic data structure"

# Merge back to the main branch

git checkout main

git merge problem1

# Push changes to GitHub

git remote add origin https://github.com/yourusername/repository-name.git

git push -u origin main

git push

Common Git Scenarios

"I made a mistake in my last commit message"

git commit --amend -m "Corrected commit message"

I want to undo a git add

git reset

"I want to undo changes I haven't committed yet"

git checkout -- filename.rs # Undo changes to specific file

git reset --hard # Undo ALL uncommitted changes (CAREFUL!)

I want to do something else

git log # shows commit history

git branch # shows available branches

git rebase # is an alternative to merge

git fetch # is like git pull but doesn't include a merge

Search and stack overflow are you friends here!

Resources for learning more and practicing

- Interactive online Git tutorial that goes a bit deeper: https://learngitbranching.js.org/

- A downloadable app with tutorials and challenges: https://github.com/jlord/git-it-electron

- Another good tutorial (examples in ruby): https://gitimmersion.com/

- Pro Git book (free online): https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2

Lecture 4 - Hello Rust!

Quick pulse check

- Who got Rust installed?

- Is anyone STILL having github authentication issues?

- How were the discussions yesterday?

- On gradescope / grade tracking and updates

How this feels is both normal and not normal

- What's a SNAFU?

So what's going well?

Think-Pair-Share

- Something you figured out after being frustrated

- A time you were able to help someone else

- An aha moment

- That you keep showing up

Rust

Learning objectives

By the end of class today you should be able to:

- Explain what a compiler and a compiled language is

- Write a simple "hello world" Rust program wiht proper syntax (

fn, brackets) - Use

rustcandcargoto compile and run Rust programs - Decide when to use mutable or immutable variables in Rust

Rust in three concepts

- Compiled

- Type-safe

- Memory-safe

What is a compiler?

What is a compiled langauge vs an interpreted one?

What is type-safety?

What is memory-safety?

Comparing to Python

R v P - Basic function writing

fn main() { println!("Hello, world!"); }

Key differences from Python:

fnkeyword for functions (what was it for python?)- Braces

{}for code blocks (...?) - Semicolons

;end statements (...?) println!is a macro (the!means macro) - more on this later

R v P - Variables, types, and mutability

fn main() { let x = 5; // immutable by default let mut y = 10; // mut makes it mutable y = 15; // this works // x = 6; // this would error! // y = "today" // this would also error! println!("x is {}, y is {}", x, y); }

Key differences from Python:

- Python: everything mutable by default

- Rust: immutable by default with unchangable types

R vs P Ownership and memory safety

import pandas as pd

def clean_data(df):

df['score'] = df['score'] * 2 # Double all scores

return df

# Original data

grades = pd.DataFrame({'name': ['Alice', 'Bob'], 'score': [85, 92]})

print("Original:", grades['score'].tolist()) # [85, 92]

# Clean the data

cleaned = clean_data(grades)

print("Cleaned:", cleaned['score'].tolist()) # [170, 184]

# Wait... what happened to our original data?

print("Original:", grades['score'].tolist()) # [170, 184] - Changed!

In Rust

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // Option 1: Take ownership (original data moves, can't use it anymore) fn clean_data_move(mut scores: Vec<i32>) -> Vec<i32> { for score in &mut scores { *score *= 2; } scores // Returns modified data, original is gone } // Option 2: Borrow mutably (explicitly allows changes) fn clean_data_borrow(scores: &mut Vec<i32>) { for score in scores { *score *= 2; } // Original data is modified, but you were explicit about it } }

Key differences from Python:

- Python: unclear when a variable might be changed -> unexpected behavior

- Rust: data moves are alwyas explicit

Compiling and running

Python: One Step (Interpreted)

python hello.py

- Python reads your code line by line and executes it immediately

- No separate compilation step needed

Rust: Two Steps (Compiled)

# Step 1: Compile (translate to machine code)

rustc hello.rs

# Step 2: Run the executable

./hello

rustcis your compilerrustctranslates your entire program to machine code- Then you run the executable (why

./?)

Rust with Cargo (two-in-one)

# Set-up steps (one time)

cargo new my_project

cd my_project

# Build and run (compiles automatically)

cargo run

- Cargo uses

rustcunder the hood

Activity

Some reminders before we look at solutions together

- Pre-work for Friday

- I have office hours today

- Homework due Monday

- Citing solutions vs breadcrumbs

Let's look at some solutions

Lecture 5 - Guessing Game Part 1

Overview of today and Monday

- Today: Part 1, in the terminal

- Monday: Part 2, in VSCode

Learning objectives

By the end of class today you should be able to:

- Use basic

cargocommands to create projects and compile rust code - Add external dependencies to a project

- Handle Rust's

Resulttype with.expect() - Recognize common Rust compilation errors

Live guessing game demo

![]() I might suggest drawing a diagram of the folder structure as we explore

I might suggest drawing a diagram of the folder structure as we explore

Key/new(ish) commands from the demo

cargo new guessing_game

nano Cargo.toml

open . # explorer . on Windows

cargo run

cargo build

cargo check

cargo run --release

./target/debug/guessing_game

Key files from the demo

Cargo.toml

Cargo.lock

.gitignore

src/main.rs

target/debug/guessing_game

target/release/guessing_game

Compiling review and reference

Option 1: Compile directly

- put the content in file

hello.rs - command line:

- navigate to this folder

rustc hello.rs- run

./helloorhello.exe

Option 2: Use Cargo

- create a project:

cargo new PROJECT-NAME - main file will be

PROJECT-NAME/src/main.rs - to build and run:

cargo run - the machine code will be in :

./target/debug/PROJECT-NAME

Different ways to run Cargo

cargo runcompiles, runs, and saves the binary/executable in/target/debugcargo buildcompiles but does not runcargo checkchecks if it compiles (fastest)cargo run --releasecreates (slowly) "fully optimized" binary in/target/release

Back to the guessing game

We're going to add this to main.rs:

use std::io; fn main() { println!("Guess the number!"); println!("Please input your guess."); let mut guess = String::new(); io::stdin() .read_line(&mut guess) .expect("Failed to read line"); println!("You guessed: {}", guess); }

cargo run

.expect() - a tricky concept

-

read_line()returns aResultwhich has two variants -OkandErr -

Okmeans the operation succeeded, and returns the successful value -

Errmeans something went wrong, and it returns a comment on what happened -

If you use

read_line()WITHOUTexpectit will compile but warn you not to do that -

If you use

read_line()WITHexpectand it saysOkthe output will be the same (user input saved toguess) -

If you use

read_line()WITHexpectand it saysErrthe program will crash and print what you wrote in.expect()

There are better ways of handling errors that we'll cover later

More on macros!

- A macro is code that writes other code for you / expands BEFORE it compiles.

- They end with ! like println!, vec!, or panic!

For example, println!("Hello"); roughly expands into

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use std::io::{self, Write}; io::stdout().write_all(b"Hello\n").unwrap(); }

while println!("Name: {}, Age: {}", name, age); expands into

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use std::io::{self, Write}; io::stdout().write_fmt(format_args!("Name: {}, Age: {}\n", name, age)).unwrap(); }

(which you can see will further expand!)

Adding a secret number

Adding to the toml:

[dependencies]

rand = "0.8.5"

Adding to main.rs

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use rand::Rng; let secret_number = rand::thread_rng().gen_range(1..=100); println!("The secret number is: {secret_number}"); }

What did all that do

cat Cargo.toml

cat Cargo.lock

cargo run

cargo run

Activity preview - let's break things!

Activity time

Debrief:

- Let's make a list together - how many did we find?

- Which error was the most confusing?

- Which error message was the most helpful?

- Did any errors surprise you?

- What patterns did you notice in how Rust reports errors?

Wrapping up

- Coffee slots this afternoon - stop by for 5 min if you want

- Homework due Monday at 11:59pm

- REMEMBER TO COMMENT what your commands do in Problem 1

- Oh My Git - check you have "gold" borders (you did at least five at the command line)

- There will ALSO be pre-work for Monday

Lecture 6 - Guessing Game Part 2: VSCode & Completing the Game

Learning objectives

By the end of class today you should be able to:

- Use VSCode with rust-analyzer and the integrated terminal for Rust development

- Start using loops and conditional logic in Rust

- Use

matchexpressions andOrderingfor comparisons - Keep your code tidy and readable with

clippy, comments, and doc strings

Why VSCode for Rust?

- Rust Analyzer: Real-time error checking, autocomplete, type hints

- Integrated terminal: No more switching windows

- Git integration: Visual diffs, staging, commits

Setting up VSCode for Rust

You'll need to have

- Installed VSCode

- Installed Rust

- Installed the rust-analyzer extension

Joey covered this in discussions - if you need help with these come talk to us

Opening our project

From the terminal:

cd guessing_game

code .

or use File -> Open Folder from VSCode

VSCode Features Demo

File Explorer & Navigation

- Side panel for project files

- Quick switching with

Cmd+P(Mac) /Ctrl+P(Windows) - Split editor views

Integrated Terminal

View → TerminalorCtrl+`- Multiple terminals

- Same commands as before:

cargo run,cargo check

Rust Analyzer in Action

- Red squiggles - Compiler errors

- Yellow squiggles - Warnings

- Hover tooltips - Type information

- Autocomplete - As you type suggestions

- Format on save - Automatic code formatting

Let's see it in action!

Cargo Clippy

- Run with

cargo clippyin terminal to see suggestions - Suggests stylistic changes that won't change the function of your code (ie refactoring suggestions)

cargo clippy --fixwill automatically accept suggestions

Completing The Guessing Game

Highlights from the compiler errors activity

Let's chat about these together

- Lots of folks hit on something like this - what happened?

"1. error ""error[E0433]: failed to resolve: use of unresolved module or unlinked crate `rand`

--> main.rs:8:25"""

- Then playing around, people found:

- expected `;`, found keyword `let` (deleted a semicolon)

- invalid basic string b/c removed ""

- linking with `link.exe` failed: exit code: 1

- expected function, found macro `println` (got rid of ! in println!)

- cannot borrow `guess` as mutable, as it is not declared as mutable (got rid of mut in declaration)

- this file contains an unclosed delimiter (deleted a curly bracket)

- unresolved import `std::higang`

- failed to resolve: use of unresolved module or unlinked crate `io`

- unreachable expression (placed code after break)

Let's walk through an interesting one

One student used cargo add rand rather than manually adding rand to the dependencies (which is totally valid!), and go this. What's going on?

warning: use of deprecated function `rand::thread_rng`: Renamed to `rng`

--> src\main.rs:8:31

|

8 | let secret_number = rand::thread_rng().gen_range(1..=100);

| ^^^^^^^^^^

|

= note: `#[warn(deprecated)]` on by default

warning: use of deprecated method `rand::Rng::gen_range`: Renamed to `random_range`

--> src\main.rs:8:44

|

8 | let secret_number = rand::thread_rng().gen_range(1..=100);

| ^^^^^^^^^

warning: `scavenger_hunt` (bin ""scavenger_hunt"") generated 2 warnings

Current state (from last class):

use std::io; use rand::Rng; fn main() { println!("Guess the number!"); let secret_number = rand::thread_rng().gen_range(1..=100); println!("The secret number is: {secret_number}"); println!("Please input your guess."); let mut guess = String::new(); io::stdin() .read_line(&mut guess) .expect("Failed to read line"); println!("You guessed: {}", guess); }

Making it a real game:

- Remove the secret reveal - no cheating!

- Compare numbers - too high? too low?

- Add a loop - keep playing until correct

- Handle invalid input - what if they type "banana"?

Steps 0+1

Step 0: No cheating

We just need to delete:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { println!("The secret number is: {secret_number}"); }

Step 1: Comparing Numbers

First, we need to convert the guess to a number and compare:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use std::cmp::Ordering; // typically crate :: module :: type or crate :: module :: function // Add this after reading input: let guess: u32 = guess.trim().parse().expect("Please enter a number!"); match guess.cmp(&secret_number) { Ordering::Less => println!("Too small!"), Ordering::Greater => println!("Too big!"), Ordering::Equal => println!("You win!"), } }

Step 2: Adding the Loop

Wrap the input/comparison in a loop:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { loop { println!("Please input your guess."); // ... input code ... match guess.cmp(&secret_number) { Ordering::Less => println!("Too small!"), Ordering::Greater => println!("Too big!"), Ordering::Equal => { println!("You win!"); break; // Exit the loop } } } }

Step 3: Handling Invalid Input

Replace .expect() with proper error handling:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let guess: u32 = match guess.trim().parse() { Ok(num) => num, Err(_) => { println!("Please enter a valid number!"); continue; // Skip to next loop iteration } }; }

Back to VSCode

Completing the game

Let's paste the whole thing in and take a look

Comments & Documentation Best Practices

What would happen if you came back to this program in a month?

Inline Comments (//)

- Explain why, not what the code does

- Bad:

// Create a random number - Good:

// Generate secret between 1-100 for balanced difficulty - If it's not clear what the code does you should edit the code!

Doc Comments (///)

- Document meaningful chunks of code like functions, structs, modules

- Show up in

cargo docand IDE tooltips

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { /// Prompts user for a guess and validates input /// Returns the parsed number or continues loop on invalid input fn get_user_guess() -> u32 { // implementation... } }

The Better Comments extension

- Color-codes different types of comments in VSCode - let's paste it into

main.rsand see

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // TODO: Add input validation here // ! FIXME: This will panic on negative numbers // ? Why does this work differently on Windows? // * Important: This function assumes sorted input }

Visual Git Features:

- Source Control panel - See changed files

- Diff view - Side-by-side comparisons

- Stage changes - Click the + button

- Commit - Write message and commit

Still use terminal for:

git status- Quick overviewgit log- Commit historygit push/git pull- Syncing

Activity Time (20 minutes)

Wrap-up

What we've accomplished so far:

- Can now use shell, git, and rust all in one place (VSCode)

- We built a complete, functional game from scratch

- Started learning key Rust concepts: loops, matching, error handling

- We've practiced using GitHub Classroom - you'll use it for HW2!

Looking ahead

- HW1 due tonight at midnight

- HW2 released this evening

- Discussions tomorrow will focus on getting started on HW2

Lecture 7 - Variables and types

Logistics

- HW2 due next Wednesday

- I have office hours today

Circling back on comments

You definitely can make multi-line comments

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // This is a single-line comment let age = 25; // Comments can go at the end of lines /* This is a multi-line comment Useful for longer explanations or temporarily disabling code */ /// This is a line doc comment that sits on the OUTSIDE /** Or as a block comment (note the one ending asterisk) */ fn my_function(){ //! This is a line doc comment that sits on the INSIDE /*! this is a block doc comment that sits on the inside */ } }

Learning Objectives

- Use the

mutkeyword and shadowing withletto modify variables - Declare constants using

const - Use Rust's integer types and floating-point types and understand their ranges

- Understand rust's basic types and their sizes (ints, floats,

bool,char,&str) - Use type annotation (with

let) and type conversion (as) - Work with boolean values using logical operators (

&&,||,!) - Create, access, and destructure tuples

Variables and Mutability

Variables are by default immutable!

Let's try this and then fix it.

fn main(){ let x = 3; x = x + 1; println!("{x}") }

Why can't we do this now?

fn main(){ let mut x = 3; x = 9.5; println!("{x}") }

One way to fix - Variable shadowing: new variable with the same name

fn main(){ let solution = "4"; let solution : i32 = solution.parse() .expect("Not a number!"); let solution = solution * (solution - 1) / 2; println!("solution = {}",solution); let solution = "This is a string"; println!("solution = {}", solution); }

Why does this work even though solution isn't mutable?

Variables vs Constants

Sometimes you need values that never change and are known at compile time:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { const MAX_PLAYERS: u32 = 100; const PI: f64 = 3.14159; const GREETING: &str = "Hello, world!"; }

Constants:

- Are always immutable (no

mutallowed) - Use

constinstead oflet - Must have explicit types

- Named in

ALL_UPPERCASEby convention - Can be declared in any scope (including global)

- Must be computable at compile-time (so typically hard-coded)

When to use constants vs variables:

- Constants: Mathematical constants, configuration values, limits

- Variables: Data that might change or is computed at runtime

Types - Integers

Binary representations

Representing 13:

- In decimal (base 10): 13 = 1×10¹ + 3×10⁰

- In binary (base 2): 1101 = 1×2³ + 1×2² + 0×2¹ + 1×2⁰ = 8 + 4 + 0 + 1 = 13

For example, the number 13 in binary is 1101:

Binary: 1 1 0 1

Position: 3 2 1 0

2x^n: 8 4 2 1

Value: 8 4 0 1 → 8+4+1 = 13

T/P/S - What's the largest integer we can represent with 4 binary digits?

So what are ints, under the hood

Unsigned integers are stored in binary format.

But (signed) integers are stored in two's complement format, where:

- if the number is positive, the first bit is 0

- if the number is negative, the first bit is 1

To calculate the two's complement of a negative number, we flip all the bits and add 1.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // binary representation of 7 and -7 println!("{:032b}", 7); println!("{:032b}", -7); }

(Think/pair/share) Why do you think we do it this way?

Bits and bytes

- Bit: The smallest unit of data in computing - can store either 0 or 1

- Byte: A group of 8 bits - the basic addressable unit of memory

- Why 8 bits? 8 bits can represent 2⁸ = 256 different values (0-255)

- Computers typically address memory in byte-sized chunks

- (In sizes like "16 GB of RAM" GB refers to "gigaBYTES" not gigaBITS)

Integers come in all shapes and sizes

- unsigned integers:

u8,u16,u32,u64,u128,usize(architecture specific size)- from \(0\) to \(2^n-1\)

- signed integers:

i8,i16,i32(default),i64,i128,isize(architecture specific size)- from \(-2^{n-1}\) to \(2^{n-1}-1\)

![]() These numbers (like

These numbers (like u16) refer to bits, not bytes!

if you need to convert, use the

asoperator

i128andu128are useful for cryptography

Let's try it - min and max values of int types

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { println!("U8 min is {} max is {}", u8::MIN, u8::MAX); println!("I8 min is {} max is {}", i8::MIN, i8::MAX); println!("U16 min is {} max is {}", u16::MIN, u16::MAX); println!("I16 min is {} max is {}", i16::MIN, i16::MAX); println!("U32 min is {} max is {}", u32::MIN, u32::MAX); println!("I32 min is {} max is {}", i32::MIN, i32::MAX); println!("U64 min is {} max is {}", u64::MIN, u64::MAX); println!("I64 min is {} max is {}", i64::MIN, i64::MAX); println!("U128 min is {} max is {}", u128::MIN, u128::MAX); println!("I128 min is {} max is {}", i128::MIN, i128::MAX); println!("USIZE min is {} max is {}", usize::MIN, usize::MAX); println!("ISIZE min is {} max is {}", isize::MIN, isize::MAX); }

Different types don't play nice together

fn main(){ let x : i16 = 13; let y : i32 = -17; println!("{}", x * y); // will not work // println!("{}", (x as i32)* y); }

Be careful with math on ints

u8 is 8 bits and can store maximum value 2^8 - 1 = 255.

If we multiply: \(255*255=65025\).

How many bits do we need to store this value? We can take the log base 2 of the value.

>>> import math

>>> math.log2(255*255)

15.988706873717716

So we need 16 bits to store the product of two u8 values.

In general when we multiply two numbers of size \(n\) bits, we need \(2n\) bits to store the result.

Types - Floats

Why are they called floats?

- Two kinds:

f32andf64(default) - What do these mean?

Sizes of floats

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { println!("F32 min is {} max is {}", f32::MIN, f32::MAX); println!("F32 min is {:e} max is {:e}", f32::MIN, f32::MAX); println!("F64 min is {:e} max is {:e}", f64::MIN, f64::MAX); }

Why these sizes?

f32: 1 sign bit + 8 exponent bits + 23 significance bitsf64: 1 sign bit + 11 exponent bits + 52 significance bits

Floats and Rust's type inference system

fn main(){ let x:f32 = 4.0; let y:f32 = 4; // Will not work. It will not autoconvert for you. let z = 1.25; // won't get automatically assigned a type yet println!("{:.1}", x * z); //println!("{:.1}", (x as f64) * z); }

Formatting in println! (this didn't make it to your print-outs!)

You can control how numbers are displayed using format specifiers:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let total = 21.613749999999997; let big_number = 1_234_567.89; let small_number = 0.000123; let count = 42; // Float formatting println!("Default: {}", total); // Default: 21.613749999999997 println!("2 decimals: {:.2}", total); // 2 decimals: 21.61 println!("Currency: ${:.2}", price); // Currency: $19.99 // Scientific notation println!("Scientific: {:e}", big_number); // Scientific: 1.234568e6 println!("Scientific: {:.2e}", small_number); // Scientific: 1.23e-4 // Integer formatting println!("Default: {}", count); // Default: 42 println!("Width 5: {:5}", count); // Width 5: 42 println!("Zero-pad: {:05}", count); // Zero-pad: 00042 println!("Binary: {:b}", count); // Binary: 101010 println!("Hex: {:x}", count); // Hex: 2a }

Useful patterns:

{:.2}- 2 decimal places{:e}- scientific notation{:5}- fixed width 5{:b}- binary,{:x}- hexadecimal

Mini-Quiz

Take a minute to talk to a partner about what these do, then I'll call on you

cargo new my_projectcargo checkgit add .rustc hello.rsgit pullcargo run --releasegit commit -m "fix bug"

Types - Booleans (and logical operators)

booluses one byte of memory (why not one bit?)

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let x = true; let y: bool = false; println!("{}", x && y); // logical and println!("{}", x || y); // logical or println!("{}", !y); // logical not }

Bitwise operators (just for awareness)

There are also bitwise operators that look similar to logical operators:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let x = true; let y: bool = false; println!("{}", x & y); // bitwise and println!("{}", x | y); // bitwise or }

But they also work on integers

fn main(){ let x = 10; let y = 7; println!("{x:04b} & {y:04b} = {:04b}", x & y); println!("{x:04b} | {y:04b} = {:04b}", x | y); // println!("{}", x && y); // println!("{}", x || y); }

So the negation of an int is...

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let y = 7; println!("!{y:04b} = {:04b} or {0}", !y); }

Think/pair/share - What is this going to print?

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let y:i8 = 7; println!("{:016b}", y); println!("{:016b}", !y); println!("{:016b}", -1*y); }

Types - Characters

chardefined via single quotes, uses four bytes of memory (that's how many bits?)- For a complete list of UTF-8 characters check https://www.fileformat.info/info/charset/UTF-8/list.htm

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let x: char = 'a'; let y = '🚦'; let z = '🦕'; println!("{} {} {}", x, y, z); }

(Fun fact - try Control-Command-Space (Mac) or Windows-Key + . (Windows) to add emojis anywhere!)

Types - Strings

- A string slice (

&str) is defined via double quotes (we'll talk much more about what this means later!)

fn main() { let s1 = "Hello! How are you, 🦕?"; // type is immutable borrowed reference to a string slice: `&str` let s2 : &str = "Καλημέρα από την Βοστώνη και την DS210"; // here we make the type explicit println!("{}", s1); println!("{}\n", s2); // This doesn't work. You can't do String = &str //let s3: String = "Does this work?"; let s3: String = "Does this work?".to_string(); println!("{}", s3); let s4: String = String::from("How about this?"); println!("{}\n", s4); let s5: &str = &s3; println!("str reference to a String reference: {}\n", s5); // This won't work. // println!("{}", s1[3]); // println!("{}", s4[3]); // But you can index this way. println!("4th character of s1: {}", s1.chars().nth(3).unwrap()); println!("3rd character of s3: {}", s4.chars().nth(2).unwrap()); }

Tuples in Rust

Tuples are a general-purpose data structure that can hold multiple values of different types.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut tuple = (1, 1.1); let mut tuple2: (i32, f64) = (1, 1.1); // type annotation is optional let another = ("abc", "def", "ghi"); let yet_another: (u8, u32) = (255, 4_000_000_000); }

Accessing elements of a tuple

Rust tuples are "0-based":

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut tuple = (1,1.1); println!("({}, {})", tuple.0, tuple.1); tuple.0 = 2; println!("({}, {})",tuple.0,tuple.1); println!("Tuple is {:?}", tuple); }

We can unpack a tuple by matching a pattern

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // or pattern match and desconstruct let mut tuple = (1,1.1); let (a, b) = tuple; println!("a = {}, b = {}",a,b); }

Best Practices for tuples

When to Use Tuples:

- Small, related data: 2-4 related values

- Temporary grouping: Short-lived data combinations

- Function returns: Multiple return values

- Pattern matching: When destructuring is useful

Style Guidelines:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // Good: Clear, concise let (width, height) = get_dimensions(); // Good: Descriptive destructuring let (min_temp, max_temp, avg_temp) = analyze_temperatures(&data); // Avoid: Too many elements // let config = (true, false, 42, 3.14, "test", 100, false); // Hard to read // Avoid: Unclear meaning // let data = (42, 13); // What do these numbers represent? }

Lecture 8 - Functions in Rust

Logistics

- Coffee slots today

- HW2 due Wednesday

- The first midterm is in two weeks

Follow-up to yesterday

- 2's complement (at the board) (but also, don't worry about it)

- The

let x:u8 = 5; let y = -x;error - Going over the shakespeare problem

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lecture, students should be able to:

- Write function signatures including parameter names, types, and return types

- Create functions that return the unit type

()for side-effect-only operations - Explain the difference between an expression and a statement in Rust

- Use expressions to assign values based on conditions

Function Syntax

We've seen lots of examples like this:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn my_age_in_5_years(age: i16) -> i16 { let new_age = age + 5; return age; // you can just put "age" without return but "return" is clearer } }

General function template:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn function_name(arg_name_1:arg_type_1,arg_name_2:arg_type_2) -> type_returned // ^ This part is the "function signature" { // Do stuff // return something } // ^ This part is the "function body" and can be a statement or expression }

Statements and expressions

Just as in math when we have:

- expressions like (\(a^2 + b^2)\)

- and equations like (\(a^2 + b^2 = c^2)\)

In rust we have expressions and statements

- Expressions simplify to a value (like a math expression)

- Statements do things but don't simplify to a value (kind of like an equation?)

So -

y + 2is an expressionlet x = y + 2;is a statement

Statements and expressions can be nested

let x = y + 2; is a statement BUT it INCLUDES y + 2 which is an expression

The reverse is also true - we can build complex expressions that include statements

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let y = { let x = 2 * 3; x }; }

A statement or expression - shout it out

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let x = 5; // Statement or expression? x + 2 // Statement or expression? println!("hello"); // Statement or expression? my_function(5) // Statement or expression? let y = x + 2; // Statement or expression? { let z = 10; // Statement or expression? z * 2 // Statement or expression? } // Statement or expression? return x + 5; // Statement or expression? let x = { println!("doing work"); // Statement or expression? 42 // Statement or expression? }; // Statement or expression? }

Maybe it was too easy to cheat because...

- Statements always end with semi-colons

- Expressions never end with semi-colons

Key insight: {} blocks are expressions that evaluate to their final line (if no semicolon).

Adding a semicolon turns an expression into a statement

fn main(){ let a = { let x = 10; x + 5 // Expression }; println!("{}",a); let b = { let x = 10; x + 5; // Statement }; println!("{}",b); }

Let's look at return again now

We have two ways of returning from a function:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn my_age_in_5_years(age: i16) -> i16 { let new_age = age + 5; return new_age; } }

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn my_age_in_5_years(age: i16) -> i16 { let new_age = age + 5; new_age } }

Why are these effectively the same thing?

But what happens if you don't return anything?

fn say_hello(who:&str) { // no -> return_type here // fn say_hello(who:&str) -> () { println!("Hello, {}!",who); } fn main() { say_hello("world"); say_hello("Boston"); say_hello("DS210"); // let z = say_hello("DS210"); // println!("The function returned {:?}", z) }

Functions that return no value

Functions that don't return or end in an expression return "the unit type" ()

() is an empty tuple that takes no memory (think of an empty set!)

This lets us have "side-effects only" functions that perform actions (printing, file I/O, etc.)

Passing parameters

3 ways to pass parameters

- A parameter can be copied into a function (default for

i32,bool,f64, other basic types) - A function can take ownership of a parameter (default for

String, other complex types) - A function can borrow a parameter to "peek" at it without "owning" it (

&str,&i32)

Examples:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn greet_person(first_name: String, last_name: &str, age: u32) { // first_name now OWNS what was passed to it // last_name is BORROWING what was passed to it // age COPIED what was passed to it println!("Hello, {} {}! You are {} years old.", first_name, last_name, age); } }

We'll talk a lot more about owning vs borrowing later. For now, some simple rules to get started:

Quick Rules for Beginners:

- Use

&strfor string parameters (lets you pass in any string without taking it) - Use

&before the parameter name when you want to "peek" at data without taking it - Basic types like