Lecture 30 - File I/O and Concurrency

Logistics

- This is the last lecture on Rust implementation!

- Next we switch to algorithm theory and graph algorithms

- No handouts today - notes are posted online already though.

Key dates:

- Stack/heap and hand-coding redo later today

- Corrections in discussion on Tuesday

- HW6 due in a week

Learning objectives

By the end of today, you should be able to (with a reference):

- Read and write files in Rust for data processing

- Use NDArray for numerical computing (like NumPy)

- Have working examples you can adapt for your own projects

And without a reference:

- Understand basic concepts of concurrency

- Know when concurrency might help

- Use

par_iterto add concurrency easily in Rust

Part 1: File I/O

Why file I/O matters

In data science, you're always:

- Loading datasets (CSV, JSON, text files)

- Saving results

- Processing log files

- Reading configurations

Rust makes file I/O safe - no reading freed memory, no forgetting to close files, fewer surprise type parsing issues

Read a whole file to a string

use std::fs; fn main() { // Read entire file into a String let contents = fs::read_to_string("data.txt") // takes relative path .expect("Could not read file"); println!("File contents:\n{}", contents); }

That's it! File is automatically closed when contents goes out of scope.

Error handling: .expect() panics if file doesn't exist. For real code, use match or ?:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use std::fs; use std::io; fn read_file(path: &str) -> io::Result<String> { let contents = fs::read_to_string(path)?; Ok(contents) } }

Writing to a File

use std::fs; fn main() { let data = "Results:\n42\n100\n256\n"; fs::write("output.txt", data) .expect("Could not write file"); println!("Data written!"); }

Simple! Overwrites file if it exists, creates if it doesn't.

Processing files line by line

For large files, don't load everything into memory:

use std::fs::File; use std::io::{BufRead, BufReader}; fn main() { let file = File::open("data.txt").expect("Could not open file"); let reader = BufReader::new(file); // Buffer reads chunks efficiently for line in reader.lines() { // creates an iterator! let line = line.expect("Could not read line"); println!("Line: {}", line); } }

So... what is a buffer?

A buffer is temporary storage in memory for data being transferred

In Computer Systems Generally:

Think of a buffer as a "waiting area" for data:

- Video streaming: Buffer loads upcoming seconds of video so playback is smooth

- Printing: Print buffer holds documents waiting to print

- Copy/paste: Clipboard is a buffer holding your copied data

So... what is a buffer?

In File I/O:

Without buffering (slow):

Program asks: "Give me byte 1" -> Disk reads byte 1

Program asks: "Give me byte 2" -> Disk reads byte 2

Program asks: "Give me byte 3" -> Disk reads byte 3

Each disk read takes ~5-10 milliseconds!

With buffering (fast):

Program asks: "Give me byte 1" -> Disk reads bytes 1-8192 into buffer

Program asks: "Give me byte 2" -> Already in buffer! (instant)

Program asks: "Give me byte 3" -> Already in buffer! (instant)

...

Program asks: "Give me byte 8193" → Disk reads next 8192 bytes

Key insight: Disk I/O is ~100,000x slower than RAM access. Buffers reduce disk reads dramatically!

BufReader in Rust

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let file = File::open("data.txt")?; let reader = BufReader::new(file); // Wraps file with 8KB buffer }

BufReader reads chunks from disk and serves your program from RAM.

Practical example: Parse a data file

use std::fs::File; use std::io::BufReader; fn parse_numbers(filename: &str) -> Vec<i32> { let file = File::open(filename).expect("Could not open file"); let reader = BufReader::new(file); let mut numbers = Vec::new(); for line in reader.lines() { // First, check if we can read the line let text = match line { Ok(text) => text, Err(_) => continue, // Skip lines with read errors }; // Now try to parse the text as a number let parse_result = text.trim().parse::<i32>(); match parse_result { Ok(num) => numbers.push(num), Err(_) => {} // Skip lines that aren't valid numbers } } numbers } fn main() { let data = parse_numbers("numbers.txt"); println!("Read {} numbers", data.len()); println!("Sum: {}", data.iter().sum::<i32>()); }

Writing results to CSV

use std::fs::File; use std::io::Write; fn save_results(filename: &str, data: &[(String, i32)]) -> std::io::Result<()> { let mut file = File::create(filename)?; writeln!(file, "name,score")?; // Header for (name, score) in data { writeln!(file, "{},{}", name, score)?; } Ok(()) } fn main() { let results = vec![ ("Alice".to_string(), 95), ("Bob".to_string(), 87), ("Charlie".to_string(), 92), ]; save_results("results.csv", &results) .expect("Could not save results"); }

For real CSV parsing, use the csv crate - much more robust!

Part 2: NDArray - NumPy for Rust

If you need NumPy-like functionality in Rust:

[dependencies]

ndarray = "0.15"

Quick example:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use ndarray::prelude::*; let a = array![1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0]; let b = array![5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0]; // Element-wise operations let sum = &a + &b; // [6, 8, 10, 12] let product = &a * &b; // [5, 12, 21, 32] // Aggregations println!("Mean: {}", a.mean().unwrap()); }

When to use:

- Multi-dimensional arrays (matrices, tensors)

- Linear algebra and statistics

- Scientific computing

Not on homework or exam - just for your reference if you need it!

Part 3: Concurrency concepts (TC 12:35)

Cores and threads

Your computer has multiple cores:

- Core: A physical processing unit in your CPU that can execute instructions

- Thread: A sequence of instructions that can run independently

- Think of cores as workers, threads as tasks they can do

How many cores do you have?

- Laptop: 4-16 cores

- Server: 32-128 cores

- GPU: thousands of cores!

To use them all, you need concurrent programming

- One thread = one core doing work

- Multiple threads = multiple cores working in parallel

Example: Processing 1 million images

- Single thread (1 core working): 1 hour

- 8 threads (8 cores working): ~7.5 minutes

Reality check: Limits and challenges

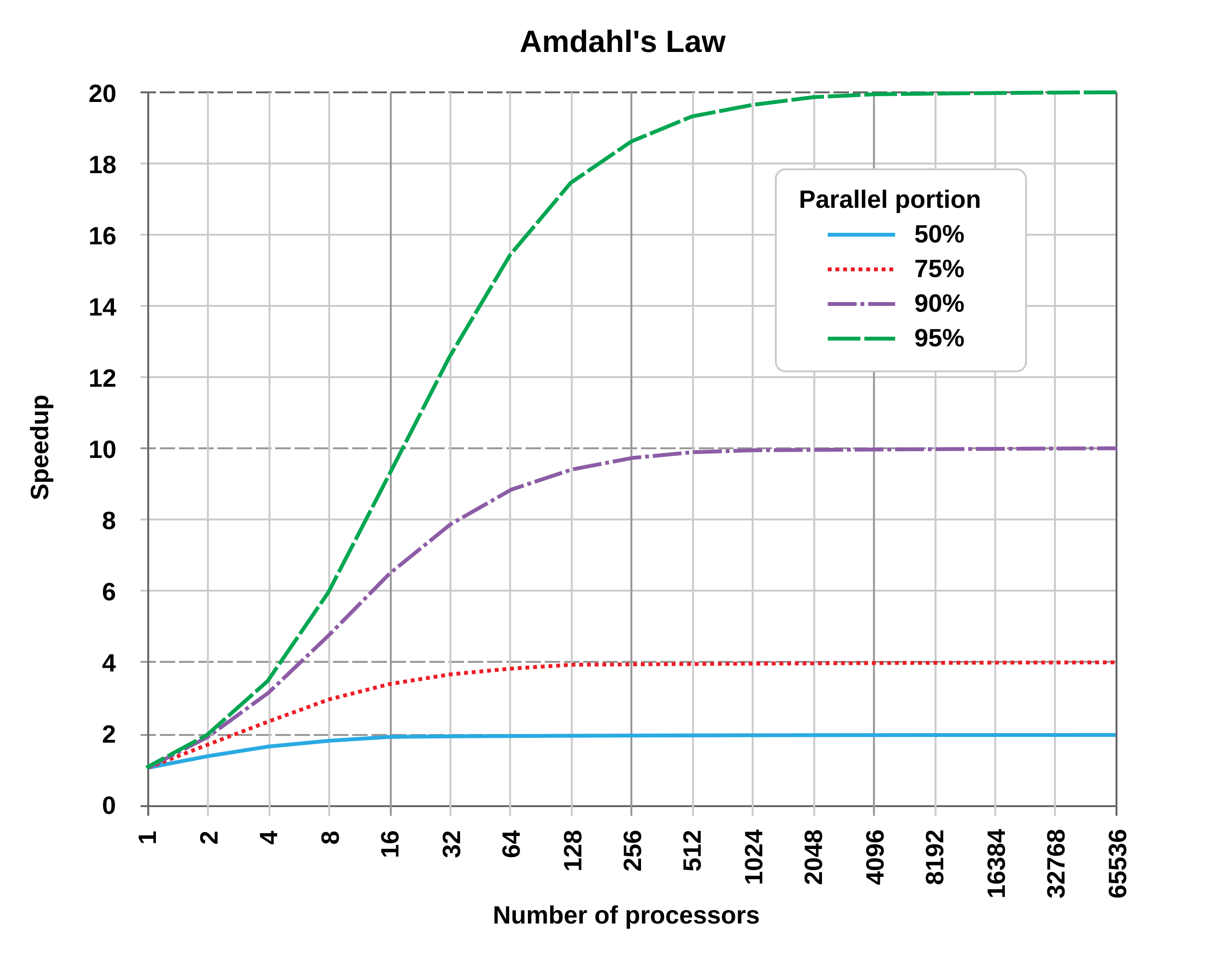

Amdahl's Law: Parallelism has limits

Not all code can be parallelized! If 50% of your program must run sequentially:

- 1 core: 100 seconds total

- 2 cores: 50 seconds parallel + 50 sequential = 75 seconds (1.33x speedup, not 2x!)

- ∞ cores: 0 seconds parallel + 50 sequential = 50 seconds (2x speedup maximum)

Key insight: The sequential portion limits your speedup, no matter how many cores you add.

Why parallel code is hard to write:

- Race conditions: Multiple threads accessing shared data can interfere with each other

- Deadlocks: Threads waiting for each other can freeze the program

- Difficult debugging: Bugs may only appear sometimes (non-deterministic)

- Overhead: Creating/coordinating threads takes time and memory

- Not all problems parallelize well: Some tasks are inherently sequential

Bottom line: Concurrency is powerful but requires careful design!

Visualizing a data race

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // BROKEN CODE (doesn't compile in Rust, thank goodness!) let mut counter = 0; thread 1: counter = counter + 1; thread 2: counter = counter + 1; }

What happens:

Time Thread 1 Thread 2 Counter

---- -------- -------- -------

t0 0

t1 Read: 0

t2 Read: 0 0

t3 Add 1: 1

t4 Add 1: 1 0

t5 Write: 1 1

t6 Write: 1 1 ← Should be 2!

Result: Lost update! This is a data race.

Other concurrency bugs

Deadlock

Thread 1 Thread 2

-------- --------

Lock A Lock B

Lock B (wait...) Lock A (wait...)

Both stuck forever!

Use-After-Free (in unsafe languages)

Thread 1 Thread 2

-------- --------

Use data

Free data

Use data again <- Crash!

These bugs are:

- Hard to reproduce (timing-dependent)

- Hard to debug (non-deterministic)

- Cause production failures

How Rust prevents concurrency bugs

Remember the borrow checker?

It prevents concurrency bugs at compile time!

Rules that help:

- Ownership: Can't have two owners (can't have unsynchronized access)

- Borrowing: Can't have

&mutwhile&exists (prevents races) - Lifetimes: References can't outlive data (prevents use-after-free)

The same rules that made single-threaded code safe make concurrent code safe!

Concurrency patterns

Rust supports three main approaches to concurrent programming:

1. Message Passing

When to use: Background tasks that produce results

Example scenario: Download a file while the main program continues

Main thread: "Hey worker, download this URL"

... continues doing other work ...

Worker thread: ... downloads file ...

Worker thread: "Done! Here's the file data"

Main thread: Receives the data and processes it

Safe because: Threads don't share data - they pass ownership through messages

2. Shared State with Locks (Mutex)

When to use: Multiple threads need to update the same counter or shared resource

Example scenario: Web server counting requests

Thread 1: Lock counter -> Read: 100 -> Increment -> Write: 101 -> Unlock

Thread 2: (waiting for lock...)

Thread 2: Lock counter -> Read: 101 -> Increment -> Write: 102 -> Unlock

Thread 3: (waiting for lock...)

Safe because: Only one thread can access the data at a time

3. Data Parallelism

When to use: Processing large amounts of independent data

Example scenario: Apply a filter to 1 million images

Thread 1: Process images 1-250,000

Thread 2: Process images 250,001-500,000

Thread 3: Process images 500,001-750,000

Thread 4: Process images 750,001-1,000,000

-> 4x faster! Each thread works on different data

Safe because: Each thread works on separate chunks, no sharing

All safe because of Rust's type system!

Manual concurrency tools (advanced) (TC 12:45)

If you need fine-grained control over threads, Rust provides:

Manual thread creation

std::thread::spawnto create

Message Passing:

std::sync::mpsc

Shared State:

Arc<Mutex<T>>

BUT: These are complex and easy to get wrong!

Better option for most cases: Use the rayon crate (next slide)

- Automatic parallelism

- Much simpler to use

- Handles threading for you

The Rayon crate: Easy parallelism

For simple cases, use the rayon crate:

[dependencies]

rayon = "1.7"

use rayon::prelude::*; fn main() { let data: Vec<i32> = (1..=1000).collect(); // Parallel iterator - automatically uses all cores! let sum: i32 = data.par_iter() .map(|x| x * x) .sum(); println!("Sum: {}", sum); }

Just change .iter() to .par_iter() to get automatic parallelism!

Summary

File I/O:

- Use

fs::read_to_string()for simple file reading - Use

BufReaderfor efficient line-by-line processing - Buffers reduce disk I/O by reading chunks into memory

- Always handle errors with

Resultand?

Concurrency:

- Multiple cores can work in parallel for speedup

- Amdahl's Law: Sequential portions limit maximum speedup

- Rust prevents data races and concurrency bugs at compile time

- Use

rayonandpar_iter()for easy parallelism

When to use concurrency:

- Processing independent data items (images, records)

- Long-running computations that can be split

- NOT worth it for small tasks (overhead > benefit)