Overview of Programming languages

Learning Objectives

- Programming languages

- Describe the differences between a high level and low level programming language

- Describe the differences between an interpreted and compiled language

- Describe the differences between a static and dynamically typed language

- Know that there are different programming paradigms such as imperative and functional

- Describe the different memory management techniques

- Be able to identify the the properties of a particular language such as rust.

Various Language Levels

-

Native code

- usually compiled output of a high-level language, directly executable on target processor

-

Assembler

- low-level but human readable language that targets processor

- pros: as fine control as in native code

- cons: not portable

-

High level languages

- various levels of closeness to the architecture: from C to Prolog

- efficiency:

- varies

- could optimize better

- pros:

- very portable

- easier to build large projects

- cons:

- some languages are resource–inefficient

Assembly Language Examples

ARM X86

. text section .text

.global _start global _start

_start: section .data

mov r0, #1 msg db 'Hello, world!',0xa

ldr r1, =message len equ 0xe

ldr r2, =len section .text

mov r7, #4 _start:

swi 0 mov edx,len ;message length

mov r7, #1 mov ecx,msg ;message to write

mov ebx,1 ;file descriptor (stdout)

.data. mov eax,4 ;system call number (sys_write)

message: int 0x80 ;call kernel

.asciz "hello world!\n" mov ebx,0 ;process' exit code

len = .-message. mov eax,1 ;system call number (sys_exit)

int 0x80 ;call kernel - this interrupt won't return

Interpreted vs. compiled

Interpreted:

- An application (interpreter) reads commands one by one and executes them.

- One step process to run an application:

python hello.py

("Fully") Compiled:

- Translated to native code by compiler

- Usually more efficient

- Two steps to execute:

- Compile (Rust:

rustc hello.rs) - Run (Rust:

./hello)

- Compile (Rust:

Compiled to Intermediate Representation (IR):

- Example: Java

- Portable intermediate format

- Needs another application, Java virtual machine, that knows how to interpret it

- Example: Python

- Under some circumstances Python bytecode is created and cached in

__pycache__ - Python bytecode is platform independent and executed by the Python Virtual Machine

- Under some circumstances Python bytecode is created and cached in

Just-in-Time (JIT) compilation is an interesting wrinkle in that it can take interpreted and intermediate format languages and compile them down to machine code.

Type checking: static vs. dynamic

Dynamic (e.g., Python):

- checks if an object can be used for specific operation during runtime

- pros:

- don't have to specify the type of object

- procedures can work for various types

- faster or no compilation

- cons:

- slower at runtime

- problems are detected late

Consider the following python code.

def add(x,y):

return x + y

print(add(2,2))

print(add("a","b"))

print(add(2,"b"))

4

ab

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[1], line 6

4 print(add(2,2))

5 print(add("a","b"))

----> 6 print(add(2,"b"))

Cell In[1], line 2, in add(x, y)

1 def add(x,y):

----> 2 return x + y

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

There is optional typing specification, but it is not enforced, e.g. accepting ints.

import typing

def add(x:str, y:str) -> str:

return x + y

print(add(2,2)) # doesn't complain about getting integer types

print(add("ab", "cd"))

#print(add(2,"n"))

4

abcd

- You can use packages such as

pyrightormypyas a type checker before running your programs - Supported by VSCode python extension

Type checking: static vs. dynamic

Static (e.g, C++, Rust, OCaml, Java):

- checks if types of objects are as specified

- pros:

- faster at runtime

- type mismatch detected early

- cons:

- often need to be explicit with the type

- making procedures generic may be difficult

- potentially slower compilation

C++:

int add(int x, int y) {

return x + y;

}

Rust:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn add(x:i32, y:i32) -> i32 { x + y } }

Type checking: static vs. dynamic

Note: some languages are smart and you don't have to always specify types (e.g., OCaml, Rust)

Rust:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let x : i32 = 7; let y = 3; // Implied to be default integer type let z = x * y; // Type of result derived from types of operands }

Various programming paradigms

- Imperative

- Functional

- Object-oriented

- Declarative / programming in logic

Imperative

im·per·a·tive (adjective) -- give an authoritive command

# Python -- Imperative

def factorial(N):

ret = 1

for i in range(N):

ret = ret * i

return ret

Functional

; Scheme, a dialect of lisp -- functional

(define (factorial n) (cond ((= n 0) 1)

(t (* n (factorial (- n 1))))))

Object Oriented

// C++ -- Object oriented pattern

class Factorial {

private:

int64 value;

public:

int64 factorial(int input) {

int64 temp = 1;

for(int i=1; i<=input; i++) {

temp = temp * i;

}

value = temp

}

int64 get_factorial() {

return value;

}

}

Declarative/Logic

% Prolog -- declaritive / programming in logic

factorial(0,1). % Base case

factorial(N,M) :-

N>0, % Ensure N is greater than 0

N1 is N-1, % Decrement N

factorial(N1, M1), % Recursive call

M is N * M1. % Calculate factorial

Memory management: manual vs. garbage collection

At least 3 kinds:

- Manual (e.g. C, C++)

- Garbage collection (e.g. Java, Python)

- Ownership-based (e.g. Rust)

Manual

- Need to explicitly ask for memory and return it

- pros:

- more efficient

- better in real–time applications

- cons:

- more work for the programmer

- more prone to errors

- major vector for attacks/hacking

Example below in C++.

Garbage collection

- Memory freed automatically

- pros:

- less work for the programmer

- more difficult to make mistakes

- cons:

- less efficient

- can lead to sudden slowdowns

Ownership-Based

- Keeps track of memory object ownership

- Allows borrowing, references without borrowing, move ownership

- When object goes out of scope, Rust automatically deallocates

- Managed deterministically at compile-time, not run-time like garbage collection

We'll dive deeper into Rust ownership later.

Rust Language (Recap)

-

high–level

-

imperative

-

compiled

-

static type checking

-

ownership-based memory management

Most important difference between Python and Rust?

How do we denote blocks of code?

- Python: indentation

- Rust:

{...}

| Language | formatting | scoping |

|---|---|---|

| Python | indentation | indentation |

| Rust | indentation | braces, {} |

Example in Rust

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn hi() { println!("Hello!"); println!("How are you?"); } }

Don't be afraid of braces!!! You'll encounter them in C, C++, Java, Javascript, PHP, Rust, ...

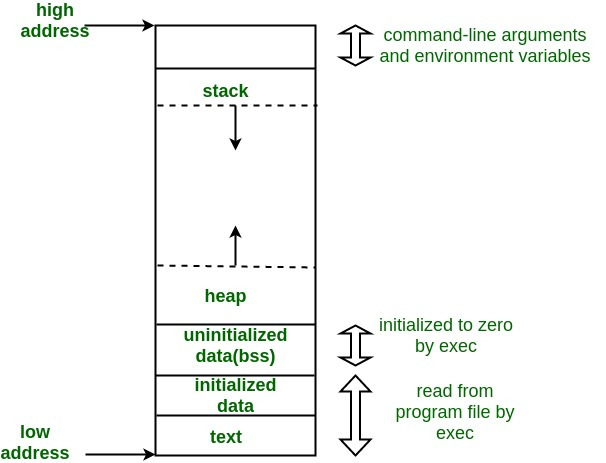

Memory Structure of an Executable Program

It's very helpful to have conceptual understanding of how memory is structured in executable programs.

The figure below illustrates a typical structure, where some low starting memory address is at the bottom and then memory addresses increase as you go up in the figure.

Here's a short description of each section starting from the bottom:

- text -- the code, e.g. program instructions

- initialized data -- explicitly initialized global/static variables

- uninitialized data (bss) -- uninitialized global/static variables, generally auto-initialied to zero. BSS -- Block Started by Symbol

- heap -- dynamically allocated memory. grows as structures are allocated

- stack -- used for local variables and function calls

Example of unsafe programming in C

Let's take a look at the problem with the following C program which asks you to guess a string and hints whether your guess was lexically less or greater.

- Copy the code into a file

unsafe.c - Compile with a local C compiler, for example,

cc unsafe.c - Execute program, e.g.

./a.out

Try with the following length guesses:

- guesses of string length <= 20

- guesses of string length > 20

- guesses of string length >> 20

Pay attention to the printout of

secretString!

Lecture Note: Switch to code

#include <signal.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(){

char loop_bool[20];

char secretString[20];

char givenString[20];

char x;

int i, ret;

memset(&loop_bool, 0, 20);

for (i=0;i<19;i++) {

x = 'a' + random() % 26;

secretString[i] = x;

}

printf("secretString: %s\n", secretString);

while (!loop_bool[0]) {

gets(givenString);

ret = strncmp(secretString, givenString, 20);

if (0 == ret) {

printf("SUCCESS!\n");

break;

}else if (ret < 0){

printf("LESS!\n");

} else {

printf("MORE!\n");

}

printf("secretString: %s\n", secretString);

}

printf("secretString: %s\n", secretString);

printf("givenString: %s\n", givenString);

return 0;

}

A Brief Aside -- The people behind the languages

Who are these people?

- Guido Van Rossum

- Graydon Hoare

- Bjarne Stroustrup

- James Gosling

- Brendan Eich

- Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie

Who are these people?

- Guido Van Rossum -- Python

- Graydon Hoare -- Rust

- Bjarne Stroustrup -- C++

- James Gosling -- Java

- Brendan Eich -- Javascript

- Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie -- C