Binary search trees

About This Module

Prework

Prework Reading

Pre-lecture Reflections

Lecture

Learning Objectives

Understand binary search trees

-

Organize data into a binary tree

-

Similar to binary heaps where the parent was greater (or lesser) than either of its children

-

Binary Search Tree: the value of a node is greater than the values of all nodes in its left subtree and less than the value of all nodes in the right subtree.

-

Enables binary search for efficient lookup, addition and removal of items.

-

Each comparison skips half of the remaining tree.

-

Complexity for search, insert and delete is , assuming balanced trees.

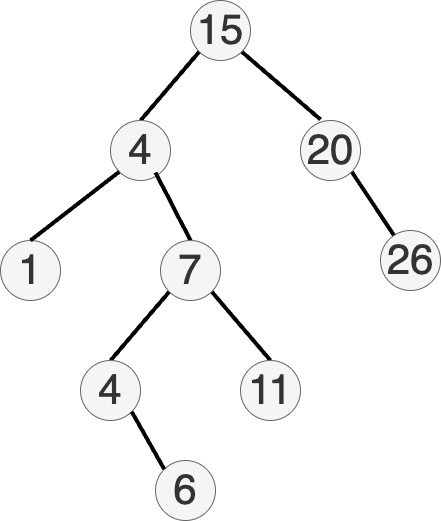

![[sample tree]](images/binary_search_tree.png)

- Invariant at each node:

- all left descendants parent

- parent all right descendants

![[sample tree]](images/relationship.png)

- Compared to binary heaps:

- different ordering of elements

Basic operations: find a key

How can we do this?

- Descend recursively from the root until found or stuck:

- If current node key is , return.

- If value at the current node, go left

- If value at the current node, go right

- If finished searching, return not found

Basic operations: insert a key

How can we do this?

- Keep descending from the root until you leave the tree

- If value at the current node, go left

- If value at the current node, go right

- Create a new node containing there

Basic operations: delete a node

How can we do this?

This can be more complicated because we might have to find a replacement.

Case 1 -- Leaf Node

If node is a leaf node, just remove and return.

Case 2 -- One Child

If node has only one child, remove and move the child up.

Example: Remove 4.

7

/ \

4 11

\

6

Remove 4 and move 6 up.

7

/ \

6 11

Case 3 -- Else

Otherwise, find the left-most descendant of the right subtree and move up.

This is the inorder successor.

Example? Remove 4.

7

/ \

4 11

/ \

2 6

/ \ / \

1 3 5 8

In this case it is 5, so replace 4 with 5.

7

/ \

5 11

/ \

2 6

/ \ \

1 3 8

Cost of these operations?

Bad news: the depth can be made proportional to , the number of nodes. How?

Good news: smart ways to make the depth

Balanced binary search trees

There are smart ways to rebalance the tree!

- Depth:

Binary search trees -- Implementation

- Applications (range searching)

- Rust:

BTreeMapandBTreeSet - Tries (Prefix Trees)

-

Let's slightly revise our

TreeNodeandBinaryTreestructs and methods. -

The main difference is the

insert_at()function.

#[derive(Debug)]

struct TreeNode {

value: usize,

left: Option<usize>,

right: Option<usize>,

}

impl TreeNode {

fn new(value: usize) -> Self {

TreeNode {

value,

left: None,

right: None,

}

}

}

#[derive(Debug)]

struct BinaryTree {

nodes: Vec<TreeNode>,

root: Option<usize>,

}

impl BinaryTree {

fn new() -> Self {

BinaryTree { nodes: Vec::new(), root: None }

}

fn insert(&mut self, value: usize) {

let new_node_index = self.nodes.len();

self.nodes.push(TreeNode::new(value));

match self.root {

Some(root_index) => self.insert_at(root_index, new_node_index, value),

None => self.root = Some(new_node_index),

}

}

fn insert_at(&mut self, current_index: usize, new_node_index: usize, value:usize) {

let current_node = &mut self.nodes[current_index];

if current_node.value < value {

if current_node.right.is_none() {

current_node.right = Some(new_node_index);

} else {

let right = current_node.right.unwrap();

self.insert_at(right, new_node_index, value);

}

} else {

if current_node.left.is_none() {

current_node.left = Some(new_node_index);

} else {

let left = current_node.left.unwrap();

self.insert_at(left, new_node_index, value);

}

}

}

}

- What happens if we insert the following values?

let mut tree = BinaryTree::new();

tree.insert(1);

tree.insert(2);

tree.insert(3);

tree.insert(6);

tree.insert(7);

tree.insert(11);

tree.insert(23);

tree.insert(34);

println!("{:#?}", tree);

BinaryTree {

nodes: [

TreeNode {

value: 1,

left: None,

right: Some(

1,

),

},

TreeNode {

value: 2,

left: None,

right: Some(

2,

),

},

TreeNode {

value: 3,

left: None,

right: Some(

3,

),

},

TreeNode {

value: 6,

left: None,

right: Some(

4,

),

},

TreeNode {

value: 7,

left: None,

right: Some(

5,

),

},

TreeNode {

value: 11,

left: None,

right: Some(

6,

),

},

TreeNode {

value: 23,

left: None,

right: Some(

7,

),

},

TreeNode {

value: 34,

left: None,

right: None,

},

],

root: Some(

0,

),

}

1

\

2

\

3

\

6

\

7

\

11

\

23

\

34

Unbalanced binary search trees can be inefficient!

This is a degenerate tree -- basically a linked list.

Balanced binary search trees

There are smart ways to rebalance the tree!

-

Depth:

-

Usually additional information has to be kept at each node

-

Many popular, efficient examples:

- Red–black trees

- AVL trees

- BTrees (Used in Rust)

- ...

Fundamentally they all support rebalancing operations using some form of tree rotation.

We'll look at some simple approaches.

Basic operations: rebalance a tree

How can we do this?

-

Quite a bit more complicated

-

One basic idea. Find the branch that has gotten too long

- Swap the parent with the child that is at the top of the branch by making the child the parent and the parent the child

- If you picked a left child take the right subtree and make it a left child of the old parent

- if you picked a right child take left subtree and make it a right child of the old parent

Example

Let's go back to our degenerate tree. It's just one long branch.

1

\

2

\

3

\

6

\

7

\

11

\

23

\

34

Step 1: Rotate around 1-2-3.

2

/ \

1 3

\

6

\

7

\

11

\

23

\

34

Step 2: Rotate around 3-6-7.

2

/ \

1 6

/ \

3 7

\

11

\

23

\

34

Step 3: Rotate around 7-11-23.

2

/ \

1 6

/ \

3 11

/ \

7 23

\

34

A simple way to rebalance a binary tree

- First do an in-order traversal to get the nodes in sorted order

- Then use the middle of the sorted vector to be the root of the tree and recursively build the rest

impl BinaryTree {

fn in_order_traversal(&self, node_index: Option<usize>)->Vec<usize> {

let mut u: Vec<usize> = vec![];

if let Some(index) = node_index {

let node = &self.nodes[index];

u = self.in_order_traversal(node.left);

let mut v: Vec<usize> = vec![node.value];

let mut w: Vec<usize> = self.in_order_traversal(node.right);

u.append(&mut v);

u.append(&mut w);

}

return u;

}

}

let mut z = tree.in_order_traversal(tree.root);

z.sort();

println!("{:?}", z);

[1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 11, 23, 34]

impl BinaryTree {

// This function recursively builds a perfectly balanced BST by:

// 1. Finding the middle element of a sorted array to use as the root

// 2. Recursively building the left and right subtrees using the elements

// before and after the middle element, respectively.

fn balance_bst(&mut self, v: &[usize], start:usize, end:usize) -> Option<usize> {

if start >= end {

return None;

}

let mid = (start+end) / 2;

let node_index = self.nodes.len();

self.insert(v[mid]);

self.nodes[node_index].left = self.balance_bst(v, start, mid);

self.nodes[node_index].right = self.balance_bst(v, mid+1, end);

Some(node_index)

}

}

let mut bbtree = BinaryTree::new();

bbtree.balance_bst(&z, 0, z.len());

println!("{:#?}", bbtree);

println!("{:?}", level_order_traversal2(&bbtree));

BinaryTree {

nodes: [

TreeNode {

value: 7,

left: Some(

1,

),

right: Some(

5,

),

},

TreeNode {

value: 3,

left: Some(

2,

),

right: Some(

4,

),

},

TreeNode {

value: 2,

left: Some(

3,

),

right: None,

},

TreeNode {

value: 1,

left: None,

right: None,

},

TreeNode {

value: 6,

left: None,

right: None,

},

TreeNode {

value: 23,

left: Some(

6,

),

right: Some(

7,

),

},

TreeNode {

value: 11,

left: None,

right: None,

},

TreeNode {

value: 34,

left: None,

right: None,

},

],

root: Some(

0,

),

}

7

3 23

2 6 11 34

1

()

Produces the result:

7

/ \

3 23

/ \ / \

2 6 11 34

/

1

Why use binary search trees?

- Hash maps and hash sets give us time operations?

Reason 1:

- Good worst case behavior: no need for a good hash function

Reason 2:

- Can answer efficiently questions such as:

- What is the smallest/greatest element?

- What is the smallest element greater than ?

- List all elements between and

Example: find the smallest element greater than

Question: How can you list all elements in order in time?

Answer: recursively starting from the root

- visit left subtree

- output current node

- visit right subtree

Outputting smallest element greater than :

- Like above, ignoring whole subtrees smaller than

- Will get the first element greater than in time

For balanced trees: listing first greater elements takes time

-Trees

Are there binary search trees in Rust's standard library?

-

Not exactly

-

Binary Search Trees are computationally very efficent for search/insert/delete ().

-

In practive, very inefficient on modern computer architectures.

- Every insert triggers a heap allocation

- Every single comparison is a cache-miss.

Enter -trees:

-

B-trees are balanced search trees where each node contains between B and 2B keys, with one more subtree than keys.

-

All leaf nodes are at the same depth, ensuring consistent O(log n) performance for search, insert, and delete operations.

-

B-trees are widely used in database systems for indexing and efficient range queries.

-

They're implemented in Rust's standard library as

BTreeMapandBTreeSetfor in-memory operations. -

The structure is optimized for both disk and memory operations, with nodes sized appropriately for the storage medium.

By CyHawk, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11701365

What does the B stand for?

Invented by Bayer and McCreight at Boeing. Suggested explanations have been Boeing, balanced, broad, bushy, and Bayer. McCreight has said that "the more you think about what the B in B-trees means, the better you understand B-trees.

BTreeSet and BTreeMap

std::collections::BTreeSet

std::collections::BTreeMap

Sets and maps, respectively

// let's create a set

use std::collections::BTreeSet;

let mut set: BTreeSet<i32> = BTreeSet::new();

set.insert(11);

set.insert(7);

set.insert(5);

set.insert(23);

set.insert(25);

// listing a range

set.range(7..25).for_each(|x| println!("{}", x));

7

11

23

// listing a range: left and right bounds and

// whether they are included or not

use std::ops::Bound::{Included,Excluded};

set.range((Excluded(5),Included(11))).for_each(|x| println!("{}", x));

7

11

// Iterating through the items is the in-order traversal that will give you sorted output

for i in &set {

println!("{}", *i);

}

5

7

11

23

25

()

// let's make a map now

use std::collections::BTreeMap;

// We can rely on type inference to avoid having to fully write out the types

let mut map = BTreeMap::new();

map.insert("DS310", "Data Mechanics");

map.insert("DS210", "Programming for Data Science");

map.insert("DS120", "Foundations of Data Science I");

map.insert("DS121", "Foundations of Data Science II");

map.insert("DS122", "Foundations of Data Science III");

// Try to find a course

if !map.contains_key("DS111") {

println!("Course not found");

}

Course not found

()

for (course, name) in &map {

println!("{course}: \"{name}\"");

}

DS120: "Foundations of Data Science I"

DS121: "Foundations of Data Science II"

DS122: "Foundations of Data Science III"

DS210: "Programming for Data Science"

DS310: "Data Mechanics"

()

Note that the keys are sorted.

// listing a range

map.range("DS000".."DS199").for_each(|(x,y)| println!("{}: \"{}\"", x, y));

DS120: "Foundations of Data Science I"

DS121: "Foundations of Data Science II"

DS122: "Foundations of Data Science III"

BTreeMap vs HashMap

-

Use HashMap when:

- You need O(1) average-case lookup time for specific keys

- You don't need to maintain any particular order of elements

- You're doing mostly individual key lookups rather than range queries

- Your keys implement

Hash,Eq, andPartialEqtraits

-

Use BTreeMap when:

- You need to efficiently list all values in a specific range

- You need ordered iteration over keys/values

- You need to find the smallest/greatest element or elements between two values

- You need consistent O(log n) performance for all operations

- Your keys implement

Ordtrait

-

Key Differences:

- HashMap provides O(1) average-case lookup but can have O(n) worst-case

- BTreeMap provides guaranteed O(log n) performance for all operations

- BTreeMap maintains elements in sorted order

- HashMap is generally faster for individual lookups when you don't need ordering

-

Practical Examples:

- Use HashMap for: counting word frequencies, caching, quick lookups

- Use BTreeMap for: maintaining ordered data, range queries, finding nearest values

-

Memory Considerations:

- HashMap may use more memory due to its underlying array structure which needs resizing (doubling and copyng) when full

- BTreeMap's memory usage is more predictable and grows linearly with the number of elements -- adds new nodes as needed.

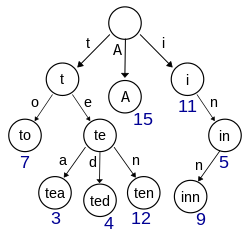

Prefix Tree (Trie)

Can be pronounced /ˈtraɪ/ (rhymes with tide) or /ˈtriː/ (tree).

A very efficient data structure for dictionary search, word suggestions, error corrections etc.

A trie for keys "A", "to", "tea", "ted", "ten", "i", "in", and "inn". Each complete English word has an arbitrary integer value associated with it. Wikipedia

Available in Rust as an external create https://docs.rs/trie-rs/latest/trie_rs/

:dep trie-rs="0.1.1"

fn testme() {

use std::str;

use trie_rs::TrieBuilder;

let mut builder = TrieBuilder::<u8>::new();

builder.push("to");

builder.push("tea");

builder.push("ted");

builder.push("ten");

builder.push("teapot");

builder.push("in");

builder.push("inn");

let trie = builder.build();

println!("Find suffixes of \"te\"");

let results_in_u8s: Vec<Vec<u8>> = trie.predictive_search("te");

let results_in_str: Vec<&str> = results_in_u8s

.iter()

.map(|u8s| str::from_utf8(u8s).unwrap())

.collect();

println!("{:?}", results_in_str);

}

testme();

Find suffixes of "te"

["tea", "teapot", "ted", "ten"]

To Insert a Word

-

Start at the Root

- Begin at the root node of the trie

- The root node represents an empty string

-

Process Each Character

- For each character in the word you want to insert:

- Check if the current node has a child node for that character

- If yes: Move to that child node

- If no: Create a new node for that character and make it a child of the current node

- For each character in the word you want to insert:

-

Mark the End

- After processing all characters, mark the final node as an end-of-word node

- This indicates that a complete word ends at this node

Let me illustrate with an example. Suppose we want to insert the word "tea" into an empty trie:

Step 1: Start at root

(root)

Step 2: Insert 't'

(root)

|

t

Step 3: Insert 'e'

(root)

|

t

|

e

Step 4: Insert 'a'

(root)

|

t

|

e

|

a*

Step 5: Mark 'a' as end-of-word (shown with *)

If we then insert "ted", the trie would look like:

(root)

|

t

|

e

/ \

a* d*

The asterisk (*) marks nodes where words end. This structure allows us to:

- Share common prefixes between words

- Efficiently search for words

- Find all words with a given prefix

- Check if a word exists in the trie

Most likely your spellchecker is based on a trie

In this case, we will compare possible close matches and then sort by frequency of occurence in some corpus and present top 3-5.

If your word is not in the trie do the following:

- Step 1: Find the largest prefix that is present and find the trie words with that prefix

- Step 2: Delete the first letter from your word and redo Step 1

- Step 3: Insert a letter (for all letters) to the beginning of the word and redo Step 1

- Step 4: Replace the beginning letter with a different one (for all letters) and redo Step 1

- Step 5: Transpose the first two letters and redo Step 1

- Step 6: Collect all words from Steps 1-5 sort by frequency of occurrence and present top 3-5 to user