Ownership and Borrowing in Rust

Introduction

- Rust's most distinctive feature: ownership system

- Enables memory safety without garbage collection

- Compile-time guarantees with zero runtime cost

- Three key concepts: ownership, borrowing, and lifetimes

Prework

Prework Readings

Read the following sections from "The Rust Programming Language" book:

- Chapter 4: Understanding Ownership - All sections

Pre-lecture Reflections

Before class, consider these questions:

- What problems does Rust's ownership system solve compared to manual memory management?

- How does ownership differ from garbage collection in other languages?

- What is the difference between moving and borrowing a value?

- When would you use

Box<T>instead of storing data on the stack? - How do mutable and immutable references help prevent data races?

Memory Layout: Stack vs Heap

Stack:

- Fast, fixed-size allocation

- LIFO (Last In, First Out) structure

- Stores data with known, fixed size at compile time

- Examples: integers, booleans, fixed-size arrays

Heap:

- Slower, dynamic allocation

- For data with unknown or variable size

- Allocator finds space and returns a pointer

- Examples: String, Vec, Box

Stack Memory Example

fn main() { let x = 5; // stored on stack let y = true; // stored on stack let z = x; // copy of value on stack println!("{}, {}", x, z); // both still valid }

- Simple types implement

Copytrait - Assignment creates a copy, both variables remain valid

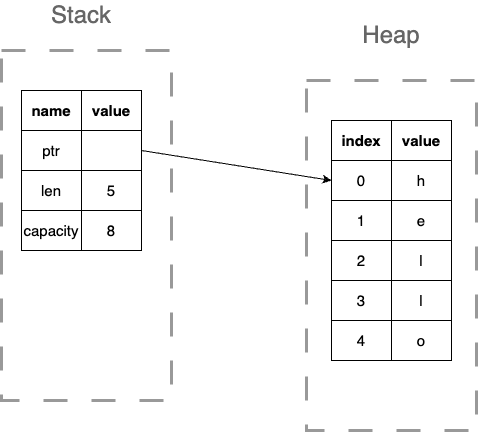

String and the Heap

Heap Memory: The String Type

Let's look more closely at the String type.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let s1 = String::from("hello"); }

Stringstores pointer, length, capacity on stack- Actual string data stored on heap

In fact we can inspect the memory layout of a String:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut s = String::from("hello"); println!("&s:{:p}", &s); println!("ptr: {:p}", s.as_ptr()); println!("len: {}", s.len()); println!("capacity: {}\n", s.capacity()); // Let's add some more text to the string s.push_str(", world!"); println!("&s:{:p}", &s); println!("ptr: {:p}", s.as_ptr()); println!("len: {}", s.len()); println!("capacity: {}", s.capacity()); }

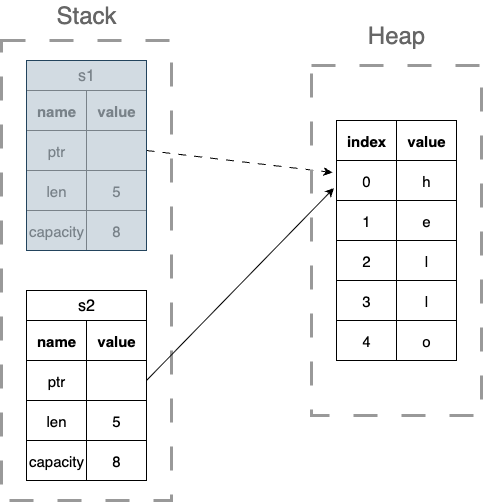

Shallow Copy with Move

fn main() { let s1 = String::from("hello"); // s1 has three parts on stack: // - pointer to heap data // - length: 5 // - capacity: 5 let s2 = s1; // shallow copy of stack data println!("{}", s1); // ERROR! s1 is no longer valid println!("{}", s2); // OK }

Stringstores pointer, length, capacity on stack- Actual string data stored on heap

Shallow Copy:

- Copying the pointer, length, and capacity

- The actual string data is not copied

- The owner of the string data is transferred to the new structure

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let s1 = String::from("hello"); println!("&s1:{:p}", &s1); println!("ptr: {:p}", s1.as_ptr()); println!("len: {}", s1.len()); println!("capacity: {}\n", s1.capacity()); let s2 = s1; println!("&s2:{:p}", &s2); println!("ptr: {:p}", s2.as_ptr()); println!("len: {}", s2.len()); println!("capacity: {}", s2.capacity()); }

The Ownership Rules

- Each value in Rust has an owner

- There can only be one owner at a time

- When the owner goes out of scope, the value is dropped

These rules prevent:

- Double free errors

- Use after free

- Data races

Ownership Transfer: Move Semantics

fn main() { let s1 = String::from("hello"); let s2 = s1; // ownership moves from s1 to s2 // s1 is now invalid - compile error if used println!("{}", s2); // OK // When s2 goes out of scope, memory is freed }

- Move prevents double-free

- Only one owner can free the memory

Clone: Deep Copy

fn main() { let s1 = String::from("hello"); let s2 = s1.clone(); // deep copy of heap data println!("s1 = {}, s2 = {}", s1, s2); // both valid }

clone()creates a full copy of heap data- Both variables are independent owners

- More expensive operation

Vec and the Heap

Vec: Dynamic Arrays on the Heap

What is Vec?

Vec<T>is Rust's growable, heap-allocated array type- Generic over type

T(e.g.,Vec<i32>,Vec<String>) - Contiguous memory allocation for cache efficiency

- Automatically manages capacity and growth

Three ways to create a Vec:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // 1. Empty vector with type annotation let v1: Vec<i32> = Vec::new(); // 2. Using vec! macro with initial values let v2 = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; // 3. With pre-allocated capacity let v3: Vec<i32> = Vec::with_capacity(10); }

Vec Memory Structure

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut v = Vec::new(); v.push(1); v.push(2); v.push(3); // Vec structure (on stack): // - pointer to heap buffer // - length: 3 (number of elements) // - capacity: (at least 3, often more) println!("&v:{:p}", &v); println!("ptr: {:p}", v.as_ptr()); println!("Length: {}", v.len()); println!("Capacity: {}", v.capacity()); }

- Pointer: points to heap-allocated buffer

- Length: number of initialized elements

- Capacity: total space available before reallocation

Vec Growth and Reallocation

fn main() { let mut v = Vec::new(); println!("Initial capacity: {}", v.capacity()); // 0 v.push(1); println!("After 1 push: {}", v.capacity()); // typically 4 v.push(2); v.push(3); v.push(4); v.push(5); // triggers reallocation println!("After 5 pushes: {}", v.capacity()); // typically 8 }

- Capacity doubles when full (amortized O(1) push)

- Reallocation: new buffer allocated, old data copied

- Pre-allocate with

with_capacity()to avoid reallocations

Accessing Vec Elements

fn main() { let v = vec![10, 20, 30, 40, 50]; // Indexing - panics if out of bounds let third = v[2]; println!("Third element: {}", third); // Using get() - returns Option<T> // Safely handles out of bounds indices match v.get(2) { Some(value) => println!("Third element: {}", value), None => println!("No element at index 2"), } }

Option<T>

Option<T> is an enum that can be either Some(T) or None.

Defined in the standard library as:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { enum Option<T> { Some(T), None, } }

Let's you handle the case where there is no return value.

fn main() { let v = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; match v.get(0) { Some(value) => println!("Element: {}", value), None => println!("No element at index"), } }

Modifying Vec Elements

fn main() { let mut v = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; // Direct indexing for modification v[0] = 10; // Adding elements v.push(6); // add to end // Removing elements let last = v.pop(); // remove from end, returns Option<T> // Insert/remove at position v.insert(2, 99); // insert 99 at index 2 v.remove(1); // remove element at index 1 println!("{:?}", v); }

Vec Ownership

fn main() { let v1 = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; let v2 = v1; // ownership moves // println!("{:?}", v1); // ERROR! println!("{:?}", v2); // OK let v3 = v2.clone(); // deep copy println!("{:?}, {:?}", v2, v3); // both OK }

- Vec follows same ownership rules as String

- Move transfers ownership of heap allocation

Functions and Ownership

Functions and Ownership

fn takes_ownership(s: String) { println!("{}", s); } // s is dropped here fn main() { let s = String::from("hello"); takes_ownership(s); // println!("{}", s); // ERROR! s was moved }

- Passing to function transfers ownership

- Original variable becomes invalid

Returning Ownership

fn gives_ownership(s: String) -> String { let new_s = s + " world"; new_s // ownership moves to caller } fn main() { let s1 = String::from("hello"); let s2 = gives_ownership(s1); println!("{}", s2); // OK }

- Return value transfers ownership out of function

- Caller becomes new owner

References: Borrowing Without Ownership

fn main() { let s1 = String::from("hello"); let len = calculate_length(&s1); // borrow with & println!("'{}' has length {}", s1, len); // s1 still valid! } fn calculate_length(s: &String) -> usize { s.len() } // s goes out of scope, but doesn't own data

&creates a reference (borrow)- Original owner retains ownership

- Reference allows reading data

Immutable References

fn main() { let s = String::from("hello"); let r1 = &s; // immutable reference let r2 = &s; // another immutable reference let r3 = &s; // yet another println!("{}, {}, {}", r1, r2, r3); // all valid // Let's take a look at the memory layout println!("&s: {:p}, s.as_ptr(): {:p}", &s, s.as_ptr()); println!("&r1: {:p}, r1.as_ptr(): {:p}", &r1, r1.as_ptr()); println!("&r2: {:p}, r2.as_ptr(): {:p}", &r2, r2.as_ptr()); println!("&r3: {:p}, r3.as_ptr(): {:p}", &r3, r3.as_ptr()); }

- Multiple immutable references allowed simultaneously

- Cannot modify through immutable reference

// ERROR fn main() { let s = String::from("hello"); change(&s); println!("{}", s); } fn change(s: &String) { s.push_str(", world"); }

Mutable References

fn main() { let mut s = String::from("hello"); change(&mut s); // mutable reference with &mut println!("{}", s); // prints "hello, world" } fn change(s: &mut String) { s.push_str(", world"); }

&mutcreates mutable reference- Allows modification of borrowed data

Mutable Reference Restrictions

fn main() { let mut s = String::from("hello"); let r1 = &mut s; let r2 = &mut s; // ERROR! Only one mutable reference println!("{}", r1); }

- Only ONE mutable reference at a time

- Prevents data races at compile time

- No simultaneous readers when there's a writer

Mixing References: Not Allowed

fn main() { let mut s = String::from("hello"); let r1 = &s; // immutable let r2 = &s; // immutable let r3 = &mut s; // ERROR! Can't have mutable with immutable println!("{}, {}", r1, r2); }

- Cannot have mutable reference while immutable references exist

- Immutable references expect data won't change

Reference Scopes and Non-Lexical Lifetimes

fn main() { let mut s = String::from("hello"); let r1 = &s; let r2 = &s; println!("{}, {}", r1, r2); // r1 and r2 no longer used after this point let r3 = &mut s; // OK! Previous references out of scope println!("{}", r3); }

- Reference scope: from introduction to last use, rather than lexical scope (till end of block)

- Non-lexical lifetimes allow more flexible borrowing

Vec with References

fn main() { let mut v = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; let first = &v[0]; // immutable borrow // v.push(6); // ERROR! Can't mutate while borrowed println!("First element: {}", first); v.push(6); // OK now, first is out of scope }

- Borrowing elements prevents mutation of Vec

- Protects against invalidation (reallocation)

Function Calls: Move vs Reference vs Mutable Reference

fn process_string(s: String) { } // takes ownership (move) fn read_string(s: &String) { } // immutable borrow fn modify_string(s: &mut String) { } // mutable borrow fn main() { let mut s = String::from("hello"); read_string(&s); // borrow modify_string(&mut s); // mutable borrow read_string(&s); // borrow again process_string(s); // move // s is now invalid }

Method Calls with Different Receivers

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { impl String { // Takes ownership: self fn into_bytes(self) -> Vec<u8> { /* ... */ } // Immutable borrow: &self fn len(&self) -> usize { /* ... */ } // Mutable borrow: &mut self fn push_str(&mut self, s: &str) { /* ... */ } } }

self: method takes ownership (consuming)&self: method borrows immutably&mut self: method borrows mutably

Method Call Examples

- It can be difficult to understand which ownership rules are being applied to a method call.

fn main() { let mut s = String::from("hello"); let len = s.len(); // &self - immutable borrow println!("{}, length: {}", s, len); s.push_str(" world 🌎"); // &mut self - mutable borrow let len = s.len(); // &self - immutable borrow println!("{}, length: {}", s, len); let bytes = s.into_bytes(); // self - takes ownership // s is now invalid println!("{:?}", bytes); let t = String::from_utf8(bytes).unwrap(); println!("{}", t); }

Vec Method Patterns

fn main() { let mut v = vec![1, 2, 3]; v.push(4); // &mut self let last = v.pop(); // &mut self, returns Option<T> let len = v.len(); // &self // Immutable iteration // What happens if you take away the &? for item in &v { // iterate with &Vec println!("{}", item); } // Mutable iteration for item in &mut v { // iterate with &mut Vec *item *= 2; println!("{}", item); } println!("{:?}", v); // Taking ownership for item in v { println!("{}", item); } //println!("{:?}", v); // ERROR! v is now invalid }

Note: It is instructive to create a Rust project and put this mode in

main.rsthen look at it in VSCode with the Rust Analyzer extension. Note the datatype decorations that VSCode places next to the variables.

Note #2: The

println!macro is pretty flexible in the types of arguments it can take. In the example above, we are passing it a&i32, a&mut i32, and ai32.

Key Takeaways

- Stack: fixed-size, fast; Heap: dynamic, flexible

- Ownership ensures memory safety without garbage collection

- Move semantics prevent double-free

- Borrowing allows temporary access without ownership transfer

- One mutable reference XOR many immutable references

- References must be valid (no dangling pointers)

- Compiler enforces these rules at compile time

Best Practices

- Prefer borrowing over ownership transfer when possible

- Use immutable references by default

- Keep mutable reference scope minimal

- Let the compiler guide you with error messages

- Clone only when necessary (performance cost)

- Understand whether functions need ownership or just access

In-Class Exercise (10 minutes)

Challenge: Fix the Broken Code

The following code has several ownership and borrowing errors. Your task is to fix them so the code compiles and runs correctly.

I'll call on volunteers to present their solutions.

fn main() { let mut numbers = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; // Task 1: Calculate sum without taking ownership let total = calculate_sum(numbers); // Task 2: Double each number in the vector double_values(numbers); // Task 3: Print both the original and doubled values println!("Original sum: {}", total); println!("Doubled values: {:?}", numbers); // Task 4: Add new numbers to the vector add_numbers(numbers, vec![6, 7, 8]); println!("After adding: {:?}", numbers); } fn calculate_sum(v: Vec<i32>) -> i32 { let mut sum = 0; for num in v { sum += num; } sum } fn double_values(v: Vec<i32>) { for num in v { num *= 2; } } fn add_numbers(v: Vec<i32>, new_nums: Vec<i32>) { for num in new_nums { v.push(num); } }

Hints:

- Think about which functions need ownership vs borrowing

- Consider when you need

&vs&mut - Remember: you can't modify through an immutable reference

- The original vector should still be usable in

mainafter function calls

Let's Review

Review solutions.