Complexity Analysis: Understanding Algorithm Performance

About This Module

This module covers algorithmic complexity analysis with a focus on how memory is managed in Rust vectors. You'll learn to analyze time and space complexity of operations and understand the performance characteristics of different data structures and algorithms.

Prework

Prework Reading

Please read the following:

- (review) Chapter 8.1: Storing Lists of Values with Vectors

- (optional) Additional reading: Wikipedia: Analysis of Algorithms

Pre-lecture Reflections

- What is the difference between time complexity and space complexity?

- Why is amortized analysis important for dynamic data structures?

- How does Rust's memory management affect algorithm complexity?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- Analyze time and space complexity using Big O notation

- Understand amortized analysis for vector operations

- Compare complexity of some algorithms and data structures

Complexity Analysis (e.g. memory management in vectors)

Let's dive deeper into algorithmic complexity analysis by considering how memory is manged in Rust Vecs.

Previously: vectors Vec<T>

- Dynamic-length array/list

- Allowed operations:

- access item at specific location

push: add something to the endpop: remove an element from the end

Other languages:

- Python: list

- C++:

vector<T> - Java:

ArrayList<T>/Vector<T>

Implementation details

Challenges

- Size changes: allocate on the heap?

- What to do if a new element added?

- Allocate a larger array and copy everything?

- Linked list?

Solution

- Allocate more space than needed!

- When out of space:

- Increase storage size by, say, 100%

- Copy everything

Under the hood

Variable of type Vec<T> contains:

- pointer to allocated memory

- size: the current number of items

- capacity: how many items could currently fit

Important: size capacity

Example (adding elements to a vector)

Method capacity() reports the current storage size

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // print out the current size and capacity // define a generic function `info` that takes one argument, `vector`, // of generic `Vec` type and prints it's length and capacity fn info<T>(vector:&Vec<T>) { println!("length = {}, capacity = {}",vector.len(),vector.capacity()); } // Let's keep adding elements to Vec and see what happens to capacity let mut v = Vec::with_capacity(7); // instantiate empty Vec with capacity 7 let mut capacity = v.capacity(); info(&v); for i in 1..=1000 { v.push(i); // push the index onto the Vec // if capacity changed, print the length and new capacity if v.capacity() != capacity { capacity = v.capacity(); info(&v); } }; info(&v); }

Example (decreasing the size of a vector)

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn info<T>(vector:&Vec<T>) { println!("length = {}, capacity = {}",vector.len(),vector.capacity()); } // what happens when we decrease the Vec by popping off values? let mut v = vec![10; 1000]; info(&v); // `while let` is a control flow construct that will continue // as long as pattern `Some(_) = v.pop()` matches. // If there is a value to pop, v.pop() returns Option enum, which // is either Some(Vec<T>) // otherwise it will return None and the loop will end. while let Some(_) = v.pop() {} info(&v); }

Questions

- What is happening as we push elements?

- When does it happen?

- How much is it changing by?

- What happens when we pop? Is capacity changing?

Example -- Shrink to Fit

- We can shrink the size of a vector manually

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn info<T>(vector:&Vec<T>) { println!("length = {}, capacity = {}",vector.len(),vector.capacity()); } let mut v = vec![10; 1000]; while let Some(_) = v.pop() {} info(&v); for i in 1..=13 { v.push(i); } info(&v); // shrink the size manually v.shrink_to_fit(); info(&v); }

Note: size and capacity not guaranteed to be the same

Example -- Creating a vector with specific capacity

Avoid reallocation if you know how many items to expect.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn info<T>(vector:&Vec<T>) { println!("length = {}, capacity = {}",vector.len(),vector.capacity()); } // creating vector with specific capacity let mut v2 : Vec<i32> = Vec::with_capacity(1234); info(&v2); }

.get() versus .pop()

.get()does not remove from the vector, but you must specify the index.pop()removes the last element from the vector- both return an

Option<T>.get()returnsSome(T)if the index is valid,Noneotherwise.pop()returnsSome(T)if the vector is not empty,Noneotherwise

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut v = Vec::new(); for i in 1..=13 { v.push(i); } println!("{:?}", v); // Does not remove from the vector, but you must specify the index println!("{:?} {:?}", v.get(v.len()-1), v); // But this one does, and removes the last element println!("{:?} {:?}", v.pop(), v); }

Other useful functions

appendAdd vector at the end of anothervec.append(&mut vec2)clearRemove all elements from the vectorvec.clear()dedupRemove consecutive identical elementsvec.dedup(), most useful when combined withsortdrainRemove a slice from the vectorvec.drain(2..4)-- removes and shifts -- expensiveremoveRemove an element from the vectorvec.remove(2)-- removes and shifts -- expensivesortSort the elements of a mutable vectorvec.sort()- Complete list at https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/vec/struct.Vec.html

Sketch of analysis: Amortization

- Inserting an element not constant time (i.e. ) under all conditions

However

-

Assumption: allocating memory size takes either or time

-

Slow operations: current_size time

-

Fast operations: time

What is the average time?

- Consider an initial 100-capacity Vec.

- Continually add element

- First 100 added elements:

- For 101st element:

So on average for the first 101 elements:

- On average: amortized time

- Fast operations pay for slow operations

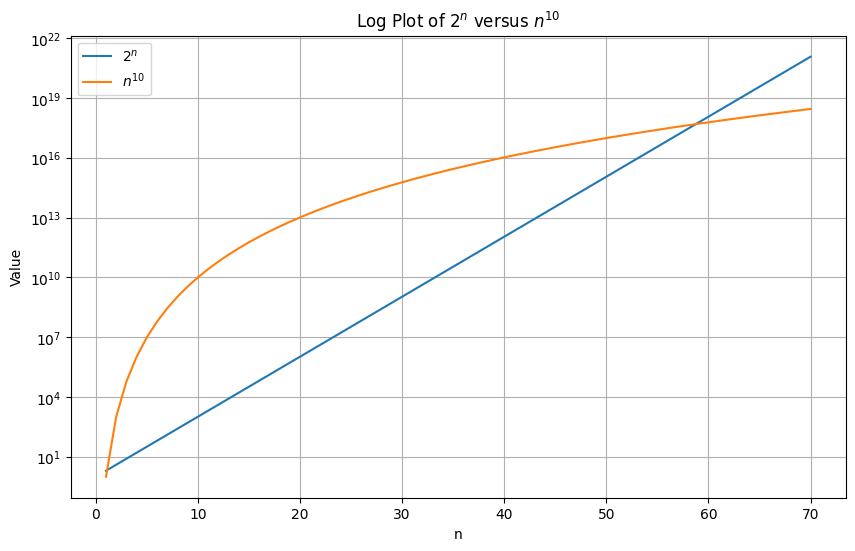

Dominant terms and constants in notation

We ignore constants and all but dominant terms as :

Which is worse? or ?

Shrinking?

- Can be implemented this way too

- Example: shrink by 50% if less than 25% used

- Most implementations don't shrink automatically

Notations

-> Algorithm takes no more than n time (worst case scenario)

-> Algorithm takes at least n time (best case scenario)

-> Average/Typical running time for the algorithm (average case scenario)

Digression (Sorting Vectors in Rust)

Sorting on on integer vectors works fine.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // This works great let mut a = vec![1, 4, 3, 6, 8, 12, 5]; a.sort(); println!("{:?}", a); }

But sorting on floating point vectors does not work directly.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // But the compiler does not like this one, since sort depends on total order let mut a = vec![1.0, 4.0, 3.0, 6.0, 8.0, 12.0, 5.0]; a.sort(); println!("{:?}", a); }

Why?

Because floats in Rust support special values like NaN and inf which don't obey normal sorting rules.

More technically, floats in Rust don't implement the

Ordtrait, only thePartialOrdtrait.The

Ordtrait is a total order, which means that for any two numbers and , either , , or .The

PartialOrdtrait is a partial order, which means that for any two numbers and , either , , , or the comparison is not well defined.

Example -- inf

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut x: f64 = 6.8; println!("{}", x/0.0); }

We can push inf onto a Vec.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut a = vec![1.0, 4.0, 3.0, 6.0, 8.0, 12.0, 5.0]; let mut x: f64 = 6.8; a.push(x/0.0); a.push(std::f64::INFINITY); println!("{:?}", a); }

Example -- NaN

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut x: f64 = -1.0; println!("{}", x.sqrt()); }

Similarly, we can push NaN onto a Vec.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut a = vec![1.0, 4.0, 3.0, 6.0, 8.0, 12.0, 5.0]; let mut x: f64 = -1.0; a.push(x.sqrt()); a.push(std::f64::NAN); println!("{:?}", a); }

Example -- Sorting with sort_by()

We can work around this by:

- not relying on the Rust implementation of

sort(), but rather - defining our own comparison function using

partial_cmp, which is a required method for the PartialOrd trait, and - using the

.sort_by()function.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // This is ok since we don't use sort, sort_by depends on the function you pass in to compute order let mut a: Vec<f32> = vec![1.0, 4.0, 3.0, 6.0, 8.0, 12.0, 5.0]; // a.sort(); a.sort_by(|x, y| x.partial_cmp(y).unwrap()); println!("{:?}", a); }

where partial_cmp is a method that returns for types that implement the PartialOrd trait:

Some(std::cmp::Ordering::Equal)when ,Some(std::cmp::Ordering::Less)whenSome(std::cmp::Ordering::Greater)whenNonewhen the comparison is not well defined, e.g x ? NaN

Example -- Can even handle inf

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut a: Vec<f32> = vec![1.0, 4.0, 3.0, std::f32::INFINITY, 6.0, 8.0, 12.0, 5.0]; println!("{:?}", a); a.sort_by(|x, y| x.partial_cmp(y).unwrap()); println!("{:?}", a); }

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut a: Vec<f32> = vec![1.0, 4.0, 3.0, std::f32::INFINITY, 6.0, std::f32::NEG_INFINITY, 8.0, 12.0, 5.0]; println!("{:?}", a); a.sort_by(|x, y| x.partial_cmp(y).unwrap()); println!("{:?}", a); }

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut a: Vec<f32> = vec![1.0, 4.0, 3.0, std::f32::INFINITY, 6.0, 8.0, std::f32::INFINITY, 12.0, 5.0]; println!("{:?}", a); a.sort_by(|x, y| x.partial_cmp(y).unwrap()); println!("{:?}", a); }

Infinity goes to the end:

Infinity has a well-defined ordering in IEEE 754 floating-point arithmetic:

- Positive infinity is explicitly defined as greater than all finite numbers

inf.partial_cmp(finite_number)returnsSome(Ordering::Greater)- This is a valid comparison, so the

unwrap_orfallback is never used - Result: infinity naturally sorts to the end

Just be careful!

It will panic if you try to unwrap a special value like NaN.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // When partial order is not well defined in the inputs you get a panic let mut a = vec![1.0, 4.0, 3.0, 6.0, 8.0, 12.0, 5.0]; let mut x: f32 = -1.0; x = x.sqrt(); a.push(x); println!("{:?}", a); a.sort_by(|x, y| x.partial_cmp(y).unwrap()); println!("{:?}", a); }

Workaround

Return a default value when the comparison is not well defined.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // When partial order is not well defined in the inputs you get a panic let mut a = vec![1.0, 4.0, 3.0, 6.0, 8.0, 12.0, 5.0]; // push a NaN (sqrt(-1.0)) let mut x: f32 = -1.0; x = x.sqrt(); a.push(x); // push an inf (10.0/0.0) a.push(10.0/0.0); println!("{:?}", a); a.sort_by(|x, y| x.partial_cmp(y).unwrap_or(std::cmp::Ordering::Less)); println!("{:?}", a); }

NaN goes to the beginning:

The .unwrap_or(std::cmp::Ordering::Less) says: "if the comparison is undefined (returns None), pretend that x is less than y".

So when NaN is compared with any other value:

NaN.partial_cmp(other)→None- Falls back to

Ordering::Less - This means NaN is always treated as "smaller than" everything else

- Result: NaN gets sorted to the beginning

In-Class Piazza Poll

Select all that are true:

-

The

push()operation on a RustVec<T>always has O(1) time complexity in the worst case. -

When a

Vec<T>runs out of capacity and needs to grow, it typically doubles its capacity, resulting in O(n) time for that specific push operation where n is the current size. -

The

pop()operation on a RustVec<T>has O(1) time complexity and automatically shrinks the vector's capacity when the size drops below 25% of capacity. -

The amortized time complexity of

push()operations on aVec<T>is O(1), meaning that averaged over many operations, each push takes constant time. - In Big O notation, O(n² + 100n + 50) simplifies to O(n²) because we ignore constants and non-dominant terms as n approaches infinity.

Solutions

Question 1: FALSE

- The

push()operation is NOT always O(1) in the worst case - When the vector needs to grow (current size equals capacity), it must:

- Allocate new memory (typically double the current capacity)

- Copy all existing elements to the new location

- This copying takes O(n) time where n is the current size

- Only when there's available capacity is push O(1)

Question 2: TRUE

- When a Vec runs out of capacity, it does typically double its capacity

- This resize operation requires allocating new memory and copying all n existing elements

- Therefore, that specific push operation takes O(n) time

- This is why we see capacity jumps in the examples (7 → 14 → 28 → 56, etc.)

Question 3: FALSE

- The

pop()operation does have O(1) time complexity (this part is true) - However,

pop()does NOT automatically shrink the vector's capacity - As shown in the examples, popping all elements leaves the capacity unchanged

- You must explicitly call

shrink_to_fit()to reduce capacity - Most implementations don't shrink automatically to avoid repeated allocate/deallocate cycles

Question 4: TRUE

- Amortized analysis averages the cost over a sequence of operations

- While occasional push operations take O(n) time (during reallocation), most take O(1)

- The expensive operations are infrequent enough that on average, each push is O(1)

- Example: For 101 pushes starting with capacity 100: (100 × 1 + 1 × 100) / 101 ≈ 2, which is still O(1)

Question 5: TRUE

- In Big O notation, we focus on the dominant term as n approaches infinity

- n² grows much faster than n or constant terms

- Therefore: O(n² + 100n + 50) → O(n²)

- We drop the constants (50), the coefficient (100), and the non-dominant term (n)