Styles of Parallel Programming

About This Module

Prework

Prework Reading

Pre-lecture Reflections

Lecture

Learning Objectives

- Instruction level parallelism (ILP)

- Done at the hardware level. CPU determines independent instructions and executes them in parallel! Often assisted by the compiler which arranges instruction so contiguous instructions can be executed concurrently.

- Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD)

- Done at the hardware level. A processor may be able to do, e.g., 1 Multiply-Accumulate of Int32, but 2 MACs per cycle for Int16 and 4 MACs per cycle of Int8.

- Thread level parallelism

- Done at the software level. Programmer or compiler decomposes program onto mostly independent parts and creates separate threads to execute them.

- Message passing between threads

- When coordination or data exchange needs arise in #3 the coordination and or data exchange happens by explicitly sending messages between threads.

- Shared memory between threads

- Threads share all the memory and use locks/barriers to coordinate between them (more below).

- Pipeline Parallelism

- Output of one thread is input to another

- Data parallelism

- Each thread works on a different part of the data

- Model parallelism (new)

- Arose due to large ML models where each thread/core has a part of the model and updates its parameters

Rust language supports thread level parallelism primitives.

We'll look at three of them (3.1, 3.2, 3.3 ) and mention the other briefly (3.4).

Processor Scaling and Multicore Architectures

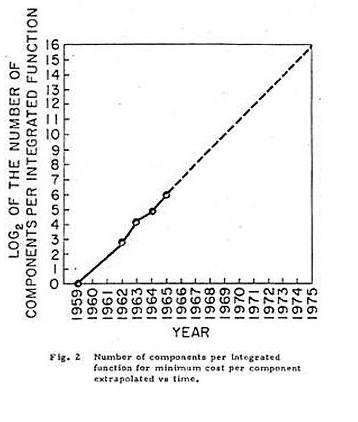

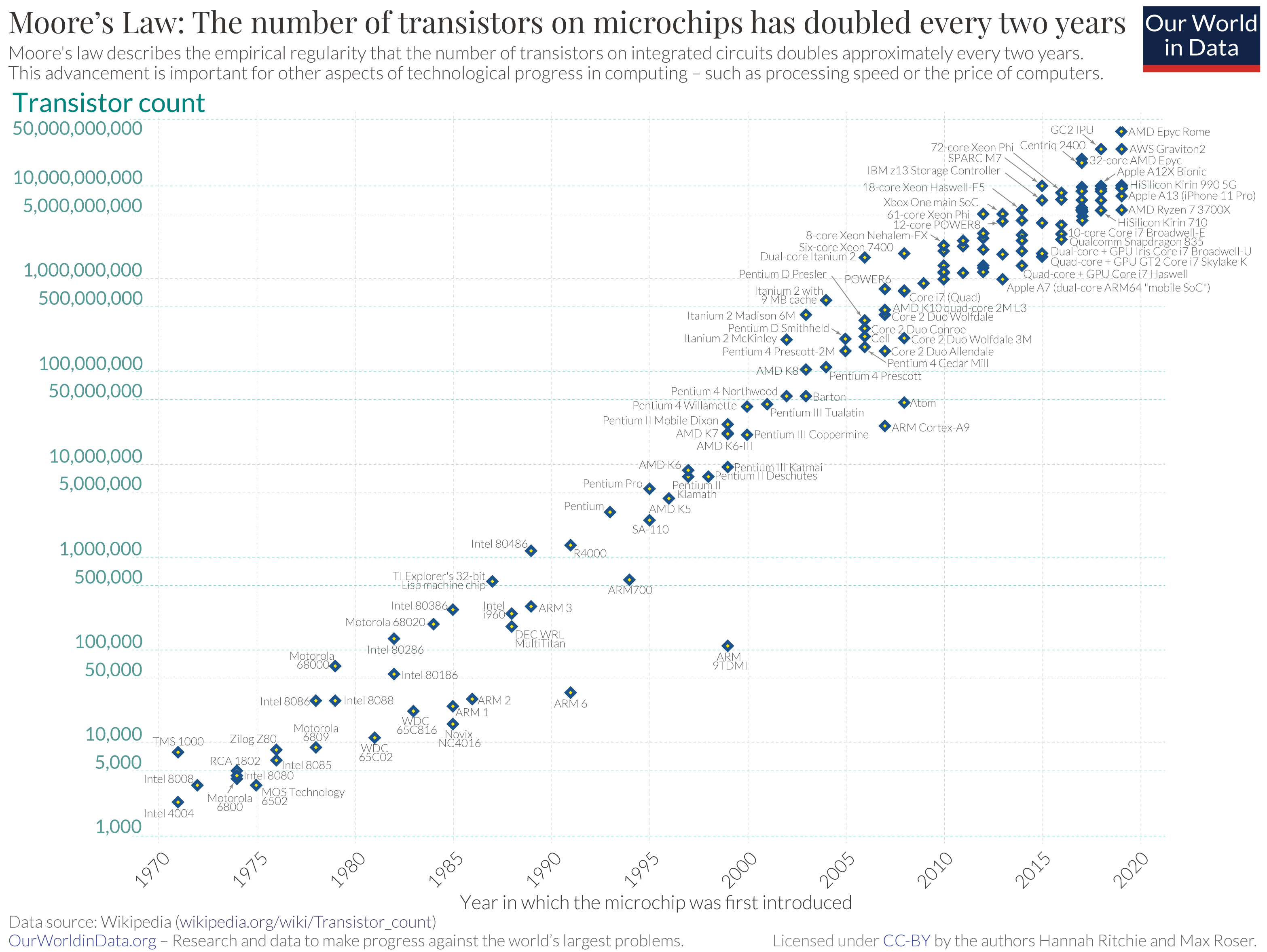

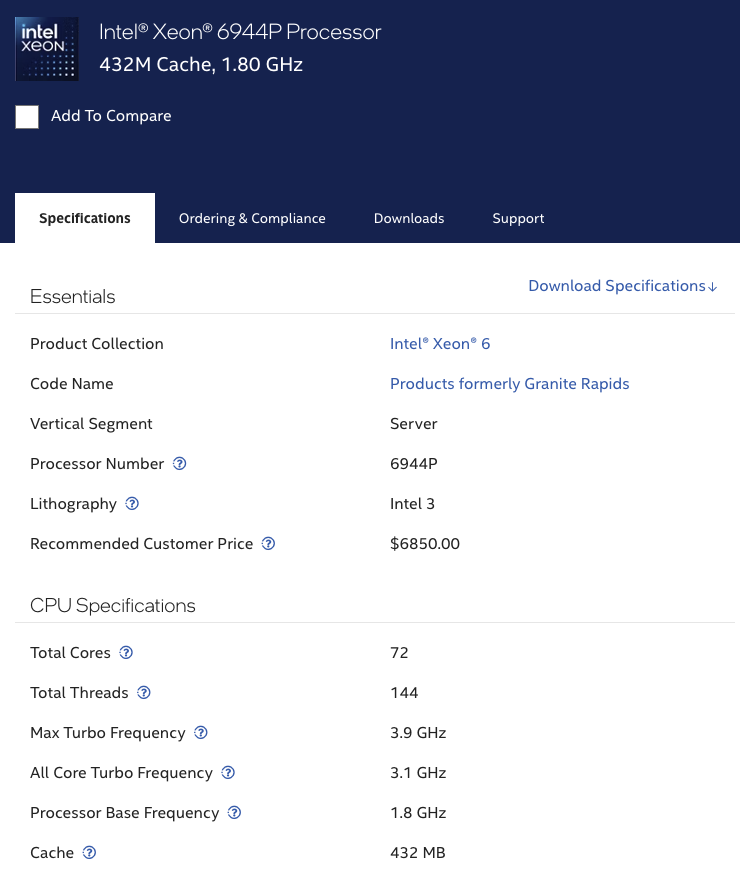

In 1965, Gordon Moore, cofounder of Intel, observed that component count of processors was doubling about every 2 years.

He predicted that it would continue for at least the next 10 years.

This became known as "Moore's Law".

In fact it has held up for over 50 years.

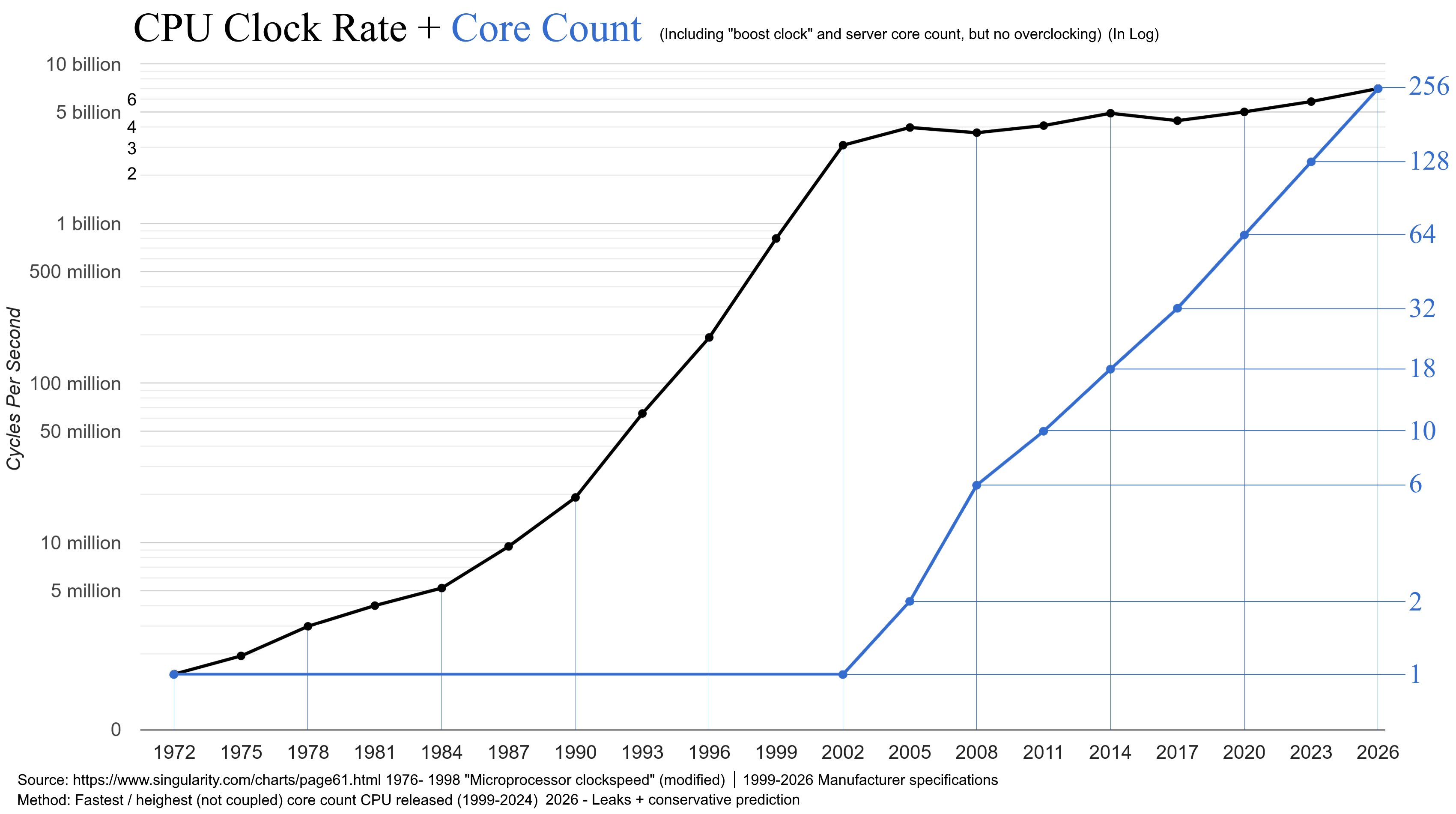

The industry did this by shrinking component size, which also allowed to increase the clock rate.

Up to a point...

Became increasingly difficult to continue to grow the transistor count...

And increasingly difficult to improve single core performance.

The alternative was to start putting more cores in the processor.

How much memory in a NVDA A100 GPU?

- 80 Gbytes of high bandwidth memory

What is the size of GPT-4?

- 1.7 trillion parameters, at 4 bytes each, 6.8 TBytes

- 1.7 trillion parameters, at 2 bytes each, 3.4 TBytes

- So clearly it will not fit in a single GPU memory

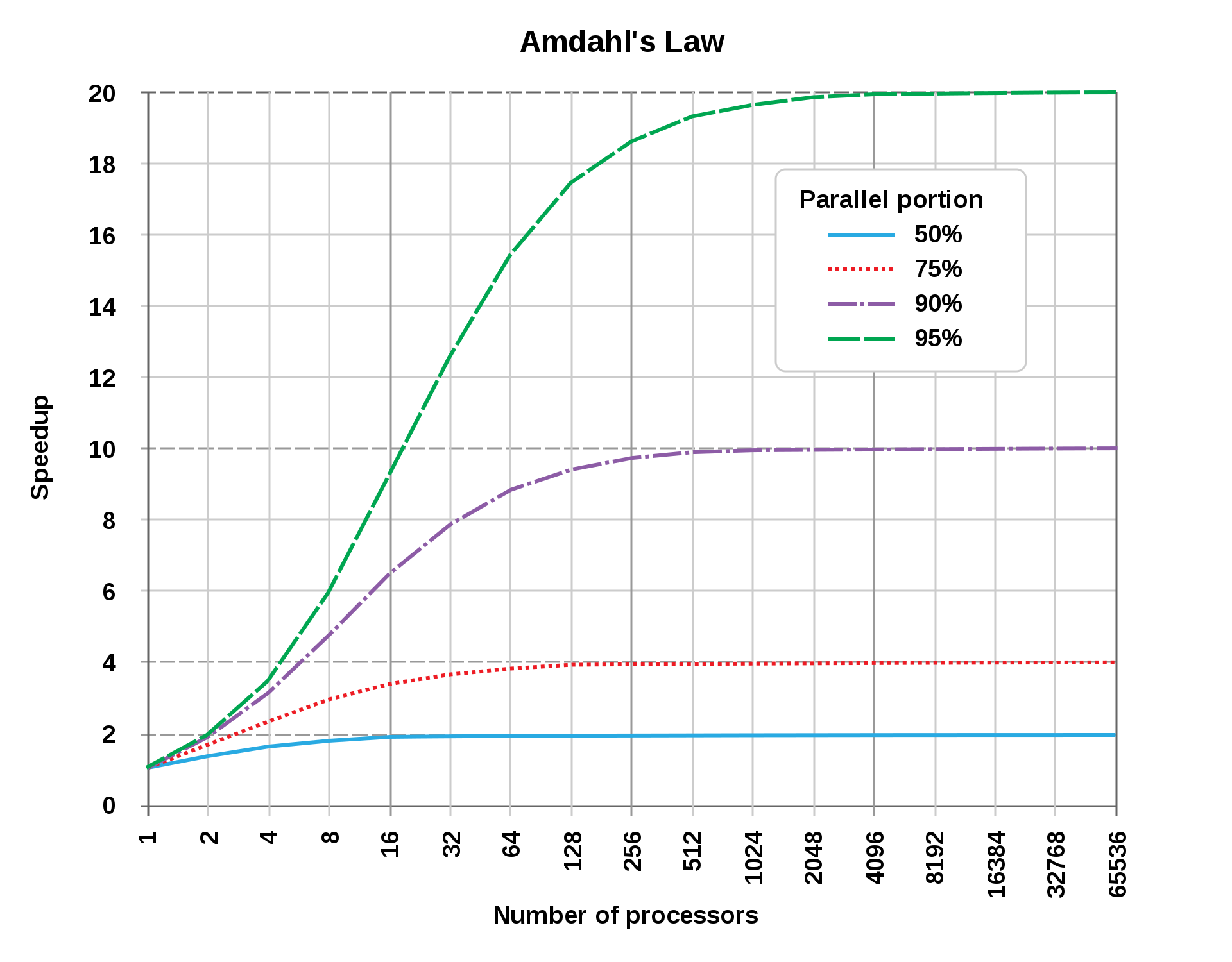

2. Limits of Parallel Programming

Let an algorithm A have a serial S and a parallel P part. Then the time to execute G is:

Running on multiple processors only affects

which as becomes

So the maximum possible speedup for a program is

3. Rust Parallel and Concurrent Programming

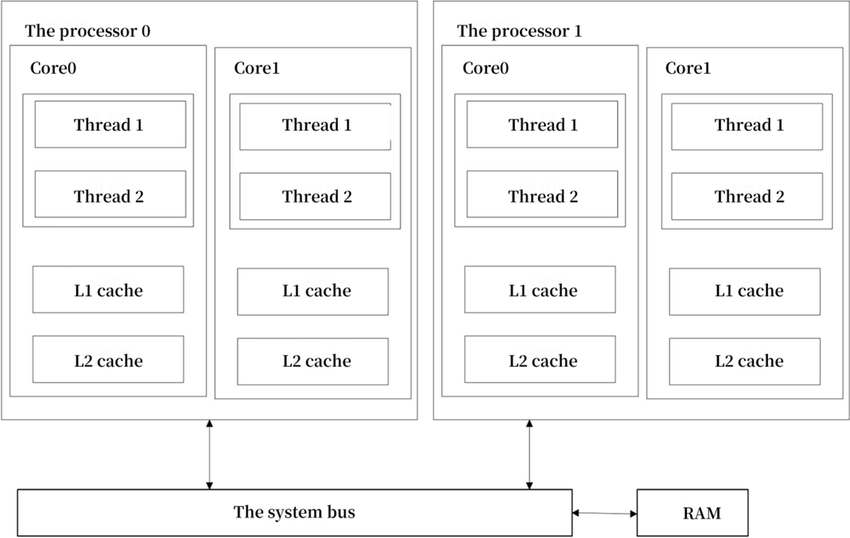

It helps to look at what constitutes a CPU core and a thread.

Intel processors have typically supported 2 threads/core.

New Mac processors typically support 1 hardware thread/core.

But the OS can support many more SW threads (thousands).

Rust libraries provide constructs for different types of parallel/concurrent programming.

- Threads (

spawn,join) - Message Passing Via Channels (

mpsc) - Shared Memory/State Concurrency using Mutexes (

mutex) - Asynchronous Programing with

Async, Await, Futures, ... Rust Lang §17

3.1 Using Threads in Rust

Examples from Rust Language Book, §16.1.

Rust let's you manually assign program code to additional threads.

Let's "spawn" a thread and print a statement 10 times with a 1 millisecond sleep between iterations.

use std::thread; use std::time::Duration; fn main(){ thread::spawn(|| { for i in 1..10 { println!("hi number {i} from the spawned thread!"); thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(1)); } }); for i in 1..5 { println!("hi number {i} from the main thread!"); thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(1)); } } main();

hi number 1 from the main thread!

hi number 1 from the spawned thread!

hi number 2 from the main thread!

hi number 2 from the spawned thread!

hi number 3 from the main thread!

hi number 3 from the spawned thread!

hi number 4 from the main thread!

hi number 4 from the spawned thread!

hi number 5 from the spawned thread!

Why did we not complete the print loop in the thread?

The main thread completed and the program shut down.

We can wait till the other thread completes using join handles.

use std::thread; use std::time::Duration; fn main() { // get a handle to the thread let handle = thread::spawn(|| { for i in 1..10 { println!("hi number {i} from the spawned thread!"); thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(1)); } }); for i in 1..5 { println!("hi number {i} from the main thread!"); thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(1)); } handle.join().unwrap(); } main();

hi number 1 from the main thread!

hi number 1 from the spawned thread!

hi number 2 from the main thread!

hi number 2 from the spawned thread!

hi number 3 from the spawned thread!

hi number 3 from the main thread!

hi number 4 from the spawned thread!

hi number 4 from the main thread!

hi number 5 from the spawned thread!

hi number 6 from the spawned thread!

hi number 7 from the spawned thread!

hi number 8 from the spawned thread!

hi number 9 from the spawned thread!

What if we want to use variables from the our main thread in the spawned thread?

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use std::thread; { let v = vec![1, 2, 3]; let handle = thread::spawn( || { println!("Here's a vector: {v:?}"); }); handle.join().unwrap(); } }

[E0373] Error: closure may outlive the current function, but it borrows `v`, which is owned by the current function

╭─[command_10:1:1]

│

6 │ ╭─▶ let handle = thread::spawn( || {

│ │ ┬┬

│ │ ╰─── help: to force the closure to take ownership of `v` (and any other referenced variables), use the `move` keyword: `move `

│ │ │

│ │ ╰── may outlive borrowed value `v`

7 │ │ println!("Here's a vector: {v:?}");

│ │ ┬

│ │ ╰── `v` is borrowed here

8 │ ├─▶ });

│ │

│ ╰───────────── note: function requires argument type to outlive `'static`

───╯

The Rust compiler won't let us borrow from a spawned thread.

We have to use the move directive.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use std::thread; { let v = vec![1, 2, 3]; let handle = thread::spawn(move || { println!("Here's a vector: {v:?}"); }); handle.join().unwrap(); } }

Here's a vector: [1, 2, 3]

()

3.2 Using Message Passing

So we spawned threads that can act completely independently.

What if we need communication or coordination between threads?

One popular pattern in many languages is message passing.

Message passing via channels.

Each channel has a Transmitter (tx) and Reciever (Rx).

std::sync::mpsc -- Multiple Producer, Single Consumer

Example with single producer, single consumer.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use std::sync::mpsc; use std::thread; { let (tx, rx) = mpsc::channel(); thread::spawn(move || { let val = String::from("hi"); tx.send(val).unwrap(); }); let received = rx.recv().unwrap(); println!("Got: {received}"); } }

Got: hi

()

Reminder that the

unwrap()

method works on the Result enum in that if the Result is Ok, it will produce the value inside the Ok. If the Result is the Err variant, unwrap will call the panic! macro.

Example with Multiple Producer, Single Consumer.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use std::sync::mpsc; use std::thread; use std::time::Duration; { let (tx, rx) = mpsc::channel(); let tx1 = tx.clone(); thread::spawn(move || { let vals = vec![ String::from("hi"), String::from("from"), String::from("the"), String::from("thread"), ]; for val in vals { tx1.send(val).unwrap(); thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1)); } }); thread::spawn(move || { let vals = vec![ String::from("more"), String::from("messages"), String::from("for"), String::from("you"), ]; for val in vals { tx.send(val).unwrap(); thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1)); } }); for received in rx { println!("Got: {received}"); } } }

Got: hi

Got: more

Got: messages

Got: from

Got: for

Got: the

Got: you

Got: thread

()

3.3 Shared Memory/State Concurrency

The other approach for coordinating between threads is to use shared memory with a mutually exclusive (Mutex) lock on the memory.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use std::sync::Mutex; { let m = Mutex::new(5); { let mut num = m.lock().unwrap(); // to access the data we have to lock it *num = 6; } // the lock released at the end of the scope println!("m = {m:?}"); } }

m = Mutex { data: 6, poisoned: false, .. }

()

What if we wanted multiple threads to increment the same counter.

We have to use Atomic Reference Counting (Arc).

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use std::sync::{Arc, Mutex}; use std::thread; { let counter = Arc::new(Mutex::new(0)); // Create an Arc on a Mutex of int32 let mut handles = vec![]; for _ in 0..10 { let counter = Arc::clone(&counter); // Use Arc::clone() method let handle = thread::spawn(move || { let mut num = counter.lock().unwrap(); // lock the counter mutex to increment it *num += 1; }); // mutex is unlocked at end of scope handles.push(handle); } for handle in handles { handle.join().unwrap(); } println!("Result: {}", *counter.lock().unwrap()); } }

Result: 10

()

3.4 Asynchronous Programming: Async, Await, Futures, etc.

This material is optional.

Rust (and other languages) have language constructs that abstracts away the particulars of managing and coordinating threads.

You can use Rust's asynchronous programming features (see Rust Book, Ch. 17) to describe which parts of your program can execute asynchronously and how to express dependency points between them.

Mixed parallel and concurrent workflow. Fig 17-3 from the Rust Book.

From Futures and the Async Syntax:

-

A future is a value that may not be ready now but will become ready at some point in the future.

-

You can apply the

asynckeyword to blocks and functions to specify that they can be interrupted and resumed. -

Within an async block or async function, you can use the

awaitkeyword to await a future- that is, wait for it to become ready.

-

Any point where you await a future within an async block or function is a potential spot for that async block or function to pause and resume.

-

The process of checking with a future to see if its value is available yet is called polling.

See Rust Book, Ch. 17 to dive deeper.

Additional Examples (Optional)

Message passing between threads

- The code demonstrates thread communication using Rust's

mpsc(multiple producer, single consumer) channels to exchange messages between threads. - Two worker threads are spawned, each with its own pair of channels for bidirectional communication with the main thread.

- The main thread coordinates the communication by receiving messages from both worker threads and sending responses back to them.

- The code uses thread synchronization primitives like

join()to ensure proper thread termination andsleep()to manage timing.

use std::thread; use std::sync::mpsc; use std::time::Duration; fn communicate(id:i32, tx: mpsc::Sender<String>, rx:mpsc::Receiver<&str>) { let t = format!("Hello from thread {}", id); tx.send(t).unwrap(); let a:&str = rx.recv().unwrap(); println!("Thread {} received {}", id, a); } fn main_thread() { let (tx1, rx1) = mpsc::channel(); let (tx2, rx2) = mpsc::channel(); // let handle1 = let handle1 = thread::spawn(move || { communicate(1, tx1, rx2); }); let (tx3, rx3) = mpsc::channel(); let (tx4, rx4) = mpsc::channel(); // let handle2 = let handle2 = thread::spawn(move || { communicate(2, tx3, rx4); }); let a:String = rx1.recv().unwrap(); let b:String = rx3.recv().unwrap(); println!("Main thread got \n{}\n{}\n\n", a, b); tx2.send("Hi from main").unwrap(); tx4.send("Hi from main").unwrap(); thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(5000)); handle1.join().unwrap(); handle2.join().unwrap(); } main_thread();

Main thread got

Hello from thread 1

Hello from thread 2

Thread 1 received Hi from main

Thread 2 received Hi from main

More example programs

Summarized by ChatGPT.

These are posted to https://github.com/trgardos/ds210-b1-sp25-lectures/tree/main/lecture_24_optional_code.

- Creates a configurable square matrix (default 64x64) and processes it in parallel using Rust's Rayon library

- Divides the matrix into chunks based on the number of specified threads, with each thread processing its assigned chunk

- Uses Rayon's

scopeandspawnfunctions for parallel execution, where each thread writes its ID number to its assigned matrix section - Includes options to configure matrix size, number of threads, and display the matrix before/after processing

- The program demonstrates parallel matrix processing with configurable parameters (matrix size, thread count, and synchronization method) using command-line arguments

- It implements three different synchronization approaches:

- Exclusive locking using

Mutex - Reader-only access using

RwLockread locks - Writer access using

RwLockwrite locks

- Exclusive locking using

- The program uses Rust's concurrency primitives:

Arcfor thread-safe shared ownershipMutexandRwLockfor synchronizationthread::spawnfor parallel execution

- Each thread processes a segment of the matrix, calculates a sum, and the program measures and reports the total execution time

- Implements parallel Gaussian elimination using Rayon's parallel iterators (

par_iter_mut) for both matrix initialization and row elimination operations - Uses thread-safe random number generation with ChaCha8Rng, where each thread gets its own seeded RNG instance

- Allows configuration of matrix size and number of threads via command-line arguments

- Includes performance timing measurements and optional matrix display functionality

- Implements Conway's Game of Life simulation with parallel processing using Rayon's concurrency primitives (

scopeandspawn) - Divides the board into chunks that are processed concurrently by multiple threads, with each thread handling a specific section of the board

- Uses command-line arguments to control simulation parameters (board size, thread count, display options, iteration count, and delay between iterations)

- Includes a glider pattern initialization and visual rendering of the board state, with timing measurements for performance analysis