Topics

- Numbering Systems

- The Von Neumann Architecture

- Memory Hierarchy and Memory Concepts

- Trends, Sizes and Costs

Numbering Systems

- Decimal (0-9) e.g. 1724

- Binary (0-1) e.g. 0b011000 (24 decimal)

- Octal (0-7) e.g. 0o131 (89 decimal)

- Hexadecimal (0-9, A-F) e.g 0x13F (319 decimal)

Converting between numbering systems

For any base b to decimal. Assume number C with digits

Between octal and binary

Every octal digit corresponds to exactly 3 binary digits and the reverse. For example 0o34 = 0b011_100. Traverse numbers right to left and prepend with 0s if necessary.

Between hexadecimal and binary

Every hexadecimal digit corresponds to exactly 4 binary digits and the reverse. For example 0x3A = 0b0011_1010. Traverse numbers right to left and prepend with 0s if necessary.

Between decimal and binary (or any base b)

More complicated. Divide repeatedly by 2 (or the base b) and keep the remainder as the next most significant binary digit. Stop when the division returns 0.

i = 0

while D > 0:

C[i] = D % 2 # modulo operator -- or substitute 2 for any base b

D = D // 2 # floor division -- or substitute 2 for any base b

i += 1

What about between decimal and octal/hexadecimal

You can use the same logic as for binary or convert to binary and then use the binary to octal/hexadecimal simple conversions

The Von Neuman Architecture

Named after the First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC written by mathematician John von Neuman in 1945.

Most processor architectures are still based on this same model.

Key Components

- Central Processing Unit (CPU):

- The CPU is the core processing unit responsible for executing instructions and performing computations. It consists of:

- Control Unit (CU):

- Directs the operations of the CPU by interpreting instructions and coordinating data flow between the components.

- Controls the flow of data between the input, memory, and output devices.

- Arithmetic/Logic Unit (ALU):

- Performs arithmetic operations (e.g., addition, subtraction) and logical operations (e.g., AND, OR, NOT).

- Acts as the computational engine of the CPU.

- Memory Unit:

- Stores data and instructions needed for processing.

- The memory serves as temporary storage for instructions being executed and intermediate data.

- It communicates with both the CPU and input/output devices.

- Input Device:

- Provides data or instructions to the CPU.

- Examples include keyboards, mice, and sensors.

- Data flows from the input device into the CPU for processing.

- Output Device:

- Displays or transmits the results of computations performed by the CPU.

- Examples include monitors, printers, and actuators.

Also known as the stored program architecture

Both data and program stored in memory and it's just convention which parts of memory contain instructions and which ones contain variables.

Two very special registers in the processor: Program Counter (PC) and Stack Pointer (SP)

PC: Points to the next instruction. Auto-increments by one when instruction is executed with the exception of branch and jmp instructions that explicitly modify it. Branch instructions used in loops and conditional statements. Jmp instructions used in function calls.

SP: Points to beginning of state (parameters, local variables, return address, old stackpointer etc) for current function call.

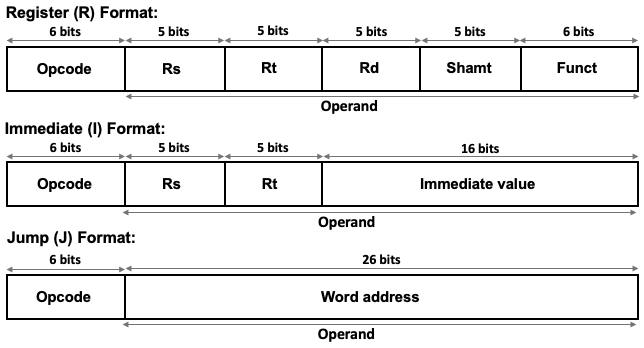

Intruction Decoding

Use the Program Counter to fetch the next instruction. After fetching you have to decode it, and subsequently to execute it.

Decoding instructions requires that you split the instruction number to the opcode (telling you what to do) and the operands (telling what data to operate one)

Example from MIPS (Microprocessor without Interlocked Pipeline Stages) Intruction Set Architecture (ISA). MIPS is RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer).

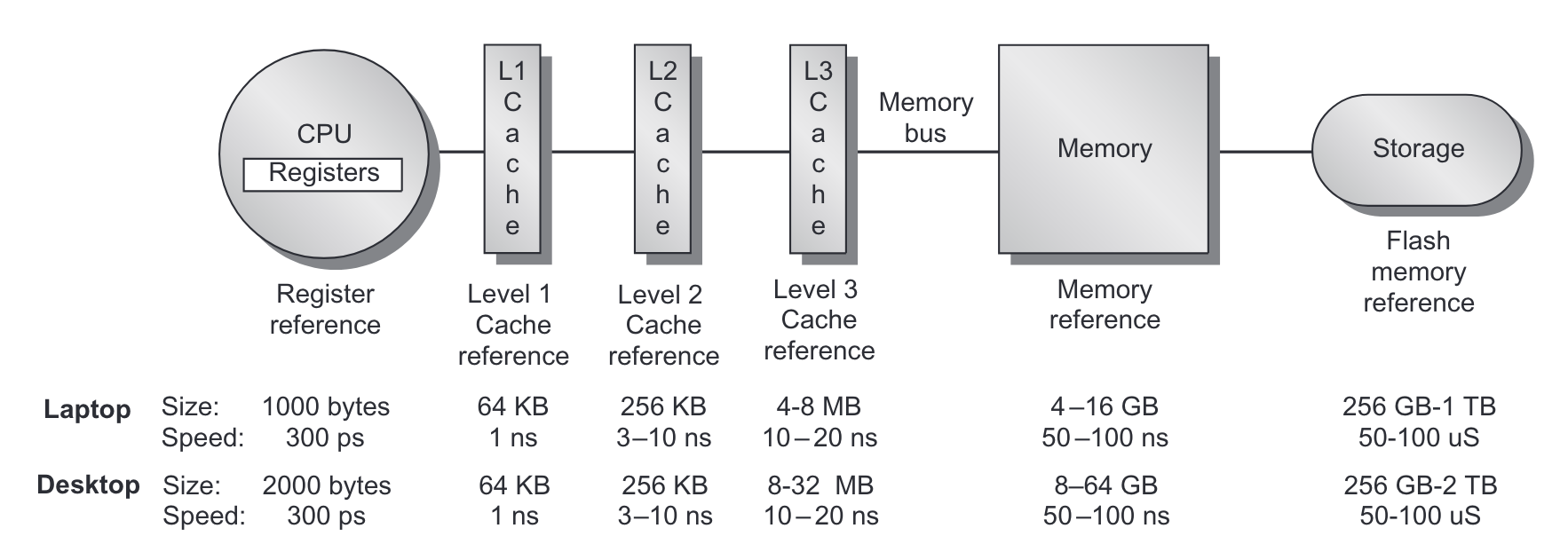

The time cost of operations

Assume for example a processor clocked at 2 GHz, e.g. .

- Executing an instruction ~ 0.5 ns (1 clock cycle)

- Getting a value (4 bytes) from L1 cache ~1 ns

- Branch mispredict ~3 ns

- Getting a value from L2 cache ~4 ns

- Send 1Kbyte of data over 1Gbps network (just send not arrive) ~ 16 ns

- Get a value from main memory ~100 ns

- Read 1MB from main memory sequentially ~1000 ns

- Compress 1Kbyte (in L1 cache) with zippy ~2000 ns

- Read 1MB from SSD ~49,000 µs

- Send a ping pong packet inside a datacenter ~500,000 ns

- Read 1Mbyte from HDD ~825,000 ns

- Do an HDD seek ~2,000,000 ns

- Send a packet from US to Europe and back ~150,000,000 ns

https://samwho.dev/numbers/

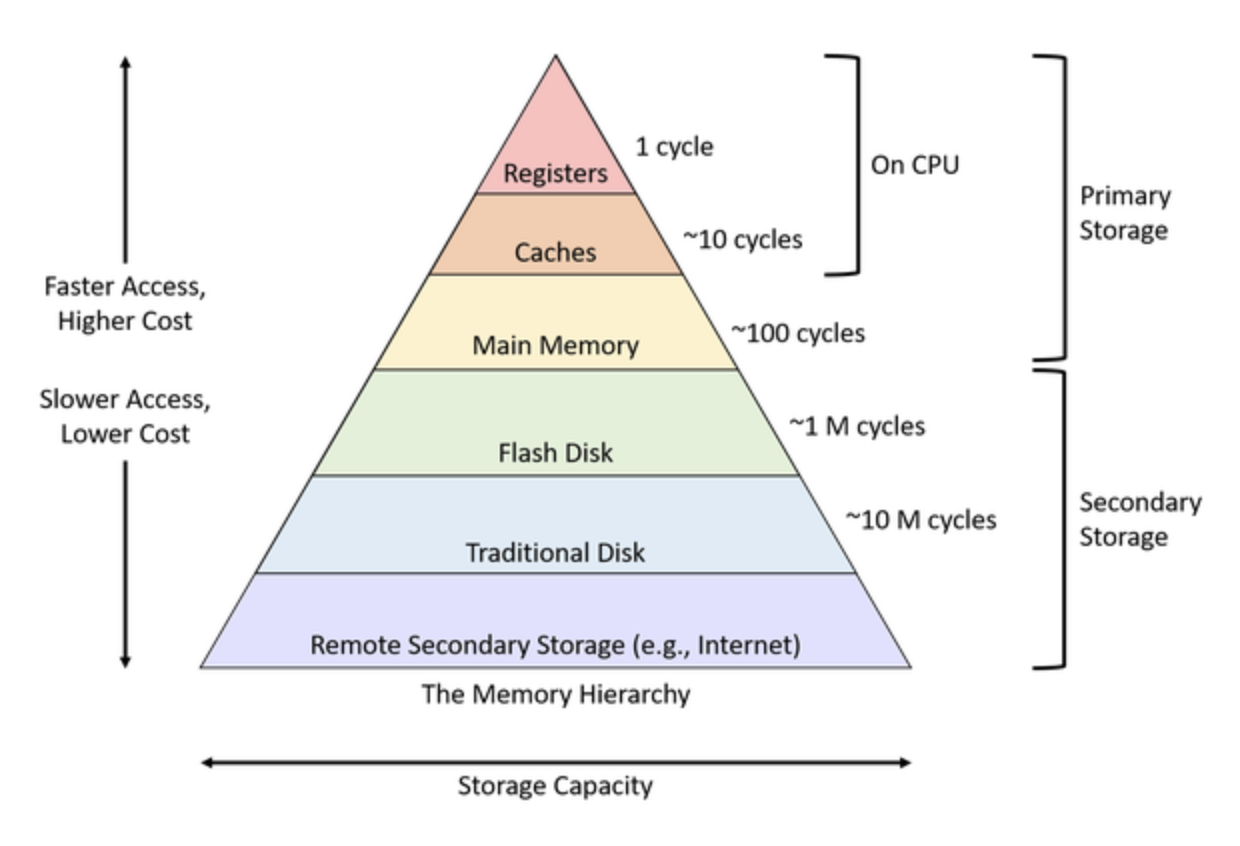

The memory hierarchy and memory concepts

We've talked about different kinds of memory. It's helpful to think of it in terms of a hierarchy.

- As indicated above, registers are closest to the processor and fastest.

- As you move farther away, the size gets larger but access gets slower

The following figure from Hennesy and Patterson is also very informative.

From Hennesy and Patterson, Computer Architecture: A Quantitative Approach_.

From Hennesy and Patterson, Computer Architecture: A Quantitative Approach_.

When the CPU tries to read from a memory location it

- First checks if that memory location is copied to L1 cache

- if it is, then the value is returned

- if it is not...

- Then checks if the memory location is copied to L2 cache

- if it is, then the value is copied to L1 cache and returned

- if it is not...

- Then checks if the memory location is copied to L3 cache

- if it is, then the value is copied to L2, then L1 and returned

- if it is not...

- Go to main memory

- fetch a cache line size of data, typically 64 bytes (why?)

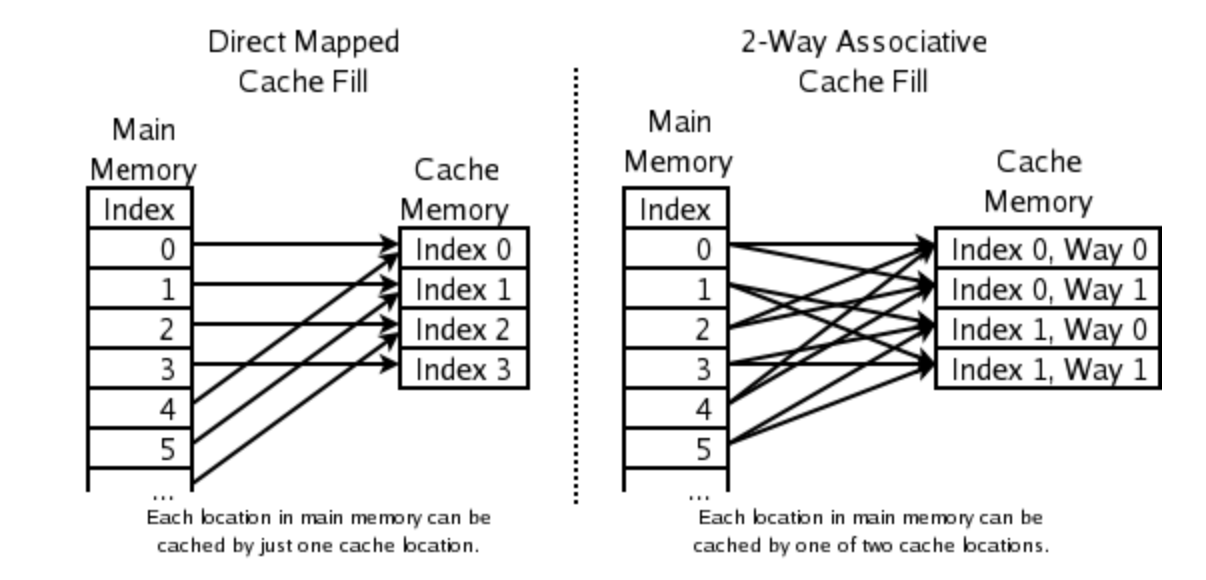

More on Caches

- Each cache line size of memory can be mapped to one of cache slots in each cache

- we say such a cache is -way

- if all slots are occupied, then we evict the Least Recently Used (LRU) slots

Direct mapped versus 2-way cache mapping. Wikipedia: CPU cache

We can see the cache configuration on a Linux system with the getconf command.

Here's the output from the MOC.

$ getconf -a | grep CACHE

LEVEL1_ICACHE_SIZE 32768 (32KB)

LEVEL1_ICACHE_ASSOC 8

LEVEL1_ICACHE_LINESIZE 64

LEVEL1_DCACHE_SIZE 32768 (32KB)

LEVEL1_DCACHE_ASSOC 8

LEVEL1_DCACHE_LINESIZE 64

LEVEL2_CACHE_SIZE 1048576 (1MB)

LEVEL2_CACHE_ASSOC 16

LEVEL2_CACHE_LINESIZE 64

LEVEL3_CACHE_SIZE 23068672 (22MB)

LEVEL3_CACHE_ASSOC 11

LEVEL3_CACHE_LINESIZE 64

LEVEL4_CACHE_SIZE 0

LEVEL4_CACHE_ASSOC 0

LEVEL4_CACHE_LINESIZE 0

How many way associative are they?

Why is 32kb not 32,000? When is K 1,000?

An 8-way associative cache with 32 KB of size and 64-byte blocks divides the cache into 64 sets, each with 8 cache lines. Memory addresses are mapped to specific sets.

Benefits of 8-Way Associativity:

- Reduces Conflict Misses:

- Associativity allows multiple blocks to map to the same set, reducing the likelihood of eviction due to conflicts.

- Balances Complexity and Performance:

- Higher associativity generally improves hit rates but increases lookup complexity. An 8-way cache strikes a good balance for most applications.

Cache Use Examples

Example from this blog post.

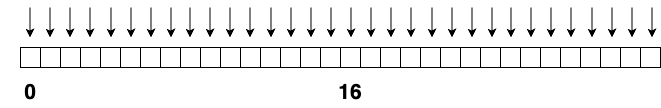

Contiguous read loop

// cache1.cpp

#include <time.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

/*

* Contiguous access loop

*

* Example from https://mecha-mind.medium.com/demystifying-cpu-caches-with-examples-810534628d71

*

* compile with `clang cache.cpp -o cache`

* run with `./cache`

*/

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

const int length = 512 * 1024 * 1024; // 512M

const int cache_line_size = 16; // size in terms of ints (4 bytes) so 16 * 4 = 64 bytes

const int m = length/cache_line_size; // 512M / 32 = 32M

printf("Looping %d M times\n", m/(1024*1024));

int *arr = (int*)malloc(length * sizeof(int)); // 512M length array

clock_t start = clock();

for (int i = 0; i < m; i++) // loop 32M times with contiguous access

arr[i]++;

clock_t stop = clock();

double duration = ((double)(stop - start)) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC * 1000;

printf("Duration: %f ms\n", duration);

free(arr);

return 0;

}

When running on Apple M2 Pro.

% clang cache1.cpp -o cache1

% ./cache1

Looping 32 M times

Duration: 54.166000 ms

Now let's modify the loop to jump by intervals of cache_line_size

Noncontiguous Read Loop

// cache2.cpp

for (int i = 0; i < m*cache_line_size; i+=cache_line_size) // non-contiguous access

arr[i]++;

clock_t stop = clock();

% ./cache2

Looping 32 M times

Duration: 266.715000 ms

About 5X slower. What happened?

Noncontiguous with 2x cache line jump

We loop half the amount of times!!

for (int i = 0; i < m*cache_line_size; i+=2*cache_line_size) {

arr[i]++;

arr[i+cache_line_size]++;

}

When running on Apple M2 Pro.

% ./cache3

Looping 16 M times

Duration: 255.551000 ms

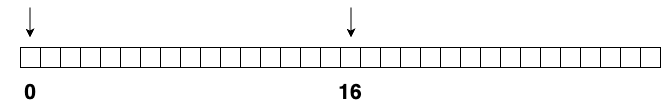

Caches on multi-processor systems

For multi-processor systems (which are now standard), memory hierarchy looks something like this:

In other words, each core has it's own L1 and L2 cache, but the L3 cache and of course main memory is shared.

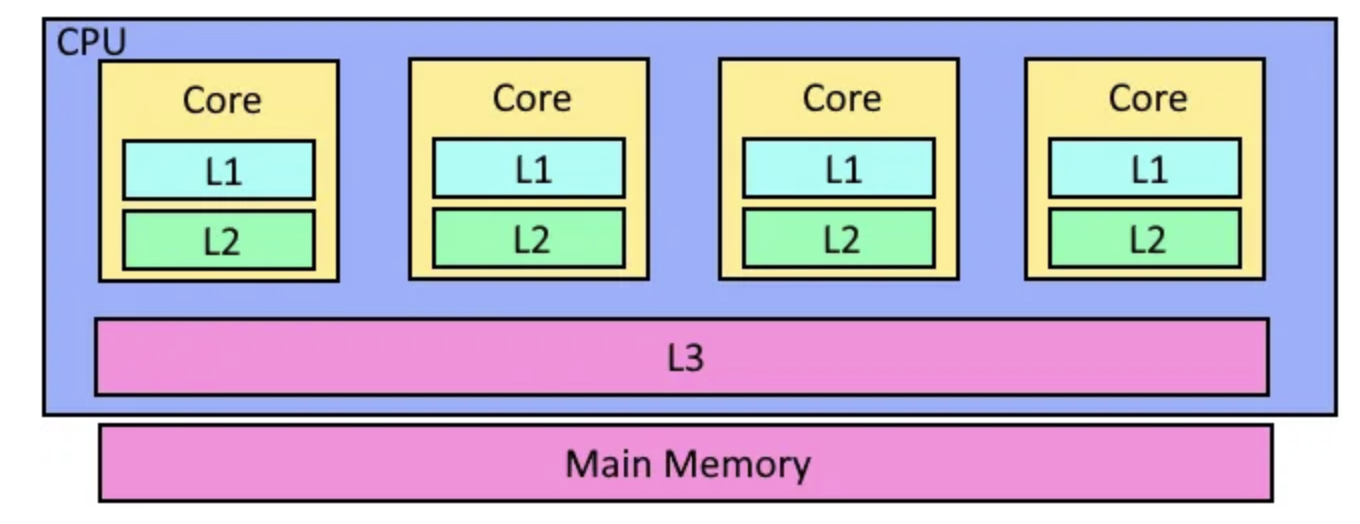

Virtual Memory, Page Tables and TLBs

- The addressable memory address range is much larger than available physical memory

- Every program thinks it can access every possible memory address.

- And there has to exist some security to prevent one program from modifying the memory occupied by another.

- The mechanism for that is virtual memory, paging and address translation

From University of Illinois CS 241 lecture notes.

From University of Illinois CS 241 lecture notes.

Page sizes are typically 4KB, 2MB or 1GB depending on the operating system.

If you access a memory address that is not paged into memory, there is a page fault while a page is possible evicted and a the memory is loaded from storage into memory.

Trends, Sizes and Costs

We'll finish by looking at some representative costs, sizes and computing "laws."

Costs

- Server GPU: \500-$1000

- DRAM: \0.05-$.01/Gbyte

- Disk: \0.02-$0.14/Gbyte

Sizes

For a typical server

2 X 2Ghz Intel/ADM processors

32-128Gbytes of memory

10-100 Tbytes of storage

10Gbps Network card

1-2 KWatts of power

For a typical datacenter

100K - 1M sercers

1+ MWatt of power

1-10 Pbbs of internal bandwidth, 1-10 Tbps of Internet facing bandwidth

1-10 Exabytes of storage

Trends

Computers grow fast so we have written some rules of thumb about them

- Kryder's Law -- Storage density doubles every 12 months

- Nielsen's Law -- Consumer Bandwidth doubles every 20 months

- Moore's Law -- CPU capacity doubles every 18 months

- Metcalfe's Law -- The value of a Network increases with the square of its members

- Bell's Law -- Every 10 years the computing paradigm changes