Graph Algorithms: Counting Triangles

About This Module

This module introduces a fundamental graph algorithm: counting triangles in a graph. You'll learn multiple approaches to solve this problem, understand their complexity trade-offs, and explore real-world applications including spam detection and social network analysis.

Prework

Prework Readings

Read the following sections from "The Rust Programming Language" book:

- Chapter 8.1: Storing Lists of Values with Vectors - Review for adjacency lists

- Chapter 6.2: The match Control Flow Construct - For recursive algorithms

- Chapter 4.3: The Slice Type - For iterating over graph data

Pre-lecture Reflections

Before class, consider these questions:

- Why might counting triangles be useful in real-world applications?

- What are the trade-offs between using adjacency matrices vs. adjacency lists?

- How does algorithm complexity change with graph density?

- What strategies can reduce duplicate counting in graph algorithms?

- When would you choose recursion vs. iteration for graph traversal?

Lecture

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you should be able to:

- Implement multiple algorithms for counting triangles in graphs

- Analyze the time complexity of different graph algorithms

- Choose appropriate graph representations for specific algorithms

- Handle duplicate counting issues in graph traversal

- Apply triangle counting to real-world problems like spam detection

- Understand the relationship between graph density and algorithm performance

Triangle Counting Problem

Problem to solve: Consider all triples of vertices. What is the number of those in which all vertices are connected? And alternatively how many unique triangles does a vertex belong to?

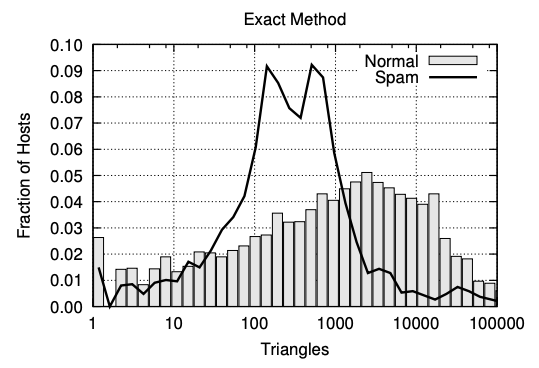

- Why is this important? Turns out that hosts that contain spam pages have a very different triangle patterns then regular hosts (https://chato.cl/papers/becchetti_2007_approximate_count_triangles.pdf)

- Also clustering coefficients in social networks: https://cs.stanford.edu/~rishig/courses/ref/l1.pdf

Enumerate explicitly over all triples and check which are triangles, using the adjacency matrix.

graph_matrix[][]

let mut count: u32 = 0;

let mut coefficients: Vec<u32> = vec![0;n];

for u in 0..n {

for v in u+1..n {

for w in v+1..n {

if (graph_matrix[u][v] && graph_matrix[v][w] && graph_matrix[w][u]) {

count += 1;

coefficients[u] += 1;

coefficients[v] += 1;

coefficients[w] += 1;

}

}

}

}

println!("{}", count);

println!("{:?}", coefficients);

2

[2, 1, 2, 1, 0, 0]

Complexity of the algorithm above is

Why?

hint: look at the nested loops.

Follow links from each vertex to see if you come back in three steps, using adjacency list.

![[sample graph]](images/sparse.png)

let mut count: u32 = 0;

for u in 0..n {

for v in &graph_list[u] { // v is the adjacency list for node u

for w in &graph_list[*v] { // w is the adjacency list for node v

for u2 in &graph_list[*w] { // now iterate through this 3rd list

if u == *u2 { // if we find the origin node, we closed the loop in 3 steps

count += 1;

break;

}

}

}

}

}

count

12

Now we need to account for duplicate counting.

For every triangle there are 2 different directions to traverse the same nodes.

For every triangle, we can start with one each of the 3 nodes to count.

// need to divide by 6

// due to symmetries triangles counted multiple times

count / (2*3)

2

Complexity

We have 4 nested loops, so worse case where every node is connected to every other node, we have complexity of .

In practice, nodes are connected more sparsely and the complexity can be shown to be , where is number of nodes and is number of edges.

Question: How did we avoid duplicate counting in the matrix version, Solution 1?

Different implementation of solution 2, using a recursive algorithm.

- Do a recursive walk through the graph and terminate after 3 steps.

- If I land where I started, then I found a triangle.

fn walk(current:usize, destination:usize, steps:usize, adjacency_list:&Vec<Vec<usize>>) -> u32 {

match steps {

0 => if current == destination {1} else {0},

_ => {

let mut count = 0;

for v in &adjacency_list[current] {

count += walk(*v,destination,steps-1,adjacency_list);

}

count

}

}

}

let mut count = 0;

for v in 0..n {

count += walk(v,v,3,&graph_list);

}

count / 6

2

For each vertex try all pairs of neighbors (via adjacency lists) and see if they are connected (via adjacency matrix).

let mut count: u32 = 0;

for u in 0..n {

let neighbors = &graph_list[u]; // get the adjacency list for node `u`

// now try all combinations of node pairs from that adjacency list

for v in neighbors {

for w in neighbors {

if graph_matrix[*v][*w] { // v,w are connected and both connected to u since they are in u's adjacency list

count += 1;

}

}

}

}

// again we duplicated counted

count / 6

2

Complexity Analysis

The code is using both an adjacency list (graph_list) and an adjacency matrix (graph_matrix) representation of the graph.

Let's break down the complexity:

- The outer loop iterates through all nodes

ufrom 0 to n-1: O(n) - For each node

u, it gets its adjacency listneighbors - For each node

vin the neighbors list, it iterates through all nodeswin the same neighbors list - For each pair (v,w), it checks if they are connected using the adjacency matrix: O(1)

The key insight is that for each node u, we're looking at all pairs of its neighbors. The number of pairs is proportional to the square of the degree of node u.

Let's denote:

- n = number of nodes

- m = number of edges

- d(u) = degree of node u

The complexity can be expressed as: Σ (d(u)²) for all nodes u

In the worst case, if the graph is complete (every node connected to every other node), each node has degree n-1, so the complexity would be O(n³).

However, in practice, most real-world graphs are sparse (m << n²). For sparse graphs, the average degree is much smaller than n. If we assume the average degree is d, then the complexity would be O(n * d²).

This is more efficient than the naive O(n³) approach of checking all possible triplets of nodes, but it's still quite expensive for dense graphs or graphs with high-degree nodes (hubs).

The final division by 6 is just a constant factor adjustment to account for counting each triangle 6 times (once for each permutation of the three nodes), so it doesn't affect the asymptotic complexity.