Graph Representation

About This Module

This module introduces graph data structures and various ways to represent graphs in computer programs. You'll learn about different graph representation methods including edge lists, adjacency lists, and adjacency matrices, along with their trade-offs and use cases.

Definition: A graph is a collection of nodes (a.k.a. vertices) connected by edges.

Prework

Prework Readings

Read the following sections from "The Rust Programming Language" book:

- Chapter 8.1: Storing Lists of Values with Vectors

- Chapter 8.3: Storing Keys with Associated Values in Hash Maps

- Chapter 6.1: Defining an Enum - For graph node representation

Pre-lecture Reflections

Before class, consider these questions:

- What real-world problems can be modeled as graphs?

- What are the trade-offs between different graph representation methods?

- How does the density of a graph affect the choice of representation?

- When would you choose an adjacency matrix vs. adjacency list?

- How do directed vs. undirected graphs differ in their representation?

Lecture

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you should be able to:

- Identify real-world problems that can be modeled as graphs

- Implement three major graph representations: edge lists, adjacency lists, and adjacency matrices

- Choose appropriate graph representations based on problem requirements

- Convert between different graph representation formats

- Understand the space and time complexity trade-offs of each representation

- Handle graphs with non-numeric vertex labels

Graph Definition and Applications

Definition: A graph is a collection of nodes (a.k.a. vertices) connected by edges.

Why are graphs useful?

Lots of problems reduce to graph problems

- The Internet is a graph: nodes are devices that have IP address, routes are edges

- (Example algorithms: Shortest path, min/max flow)

- (how many devices on the internet?)

- The Web is a graph (crawlers) (how many web pages on the internet?)

- Social networks are graphs (graph degrees, k-connectivity)

- Logistics hubs and transportation are graphs (Traveling salesman, subway and bus schedules)

- Computer scheduling (instruction dependencies)

- GSM frequency scheduling (Graph coloring -- no two connected nodes are same color)

- Medical school residency assignments (stable marriage algorithm)

- And many others....

What types of graphs are there?

- Directed vs Undirected

- Weighted (cost on the edge) vs Unweighted (all edges have same cost)

- Special

- Tree (every node has a single parent, no cycles)

- Rooted tree (single parent node, very common and useful, includes heaps, b-trees, tries etc).

- DAG (most workflows are DAGs)

- Bi-partite (can be separated to 2 sides with all edges crossing sides)

- Cliques (every node is connected to every other node)

Graph representations: various options

-

What information we want to access

-

What efficiency required

Today:

- Edges List

- Vertex Adjacency lists

- Vertex Adjacency matrix

Focus on undirected graphs:

- easy to adjust for directed

Edges List

- List of directed or undirected edges

- Can be sorted/ordered for easier access/discovery

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // number of vertices let n : usize = 6; // list of edges let edges : Vec<(usize,usize)> = vec![(0,1), (0,2), (0,3), (1,2), (2,3), (2,4), (2,5)]; println!("{:?}", edges); println!("{:?}",edges.binary_search(&(2,3))); println!("{:?}",edges.binary_search(&(1,3))); }

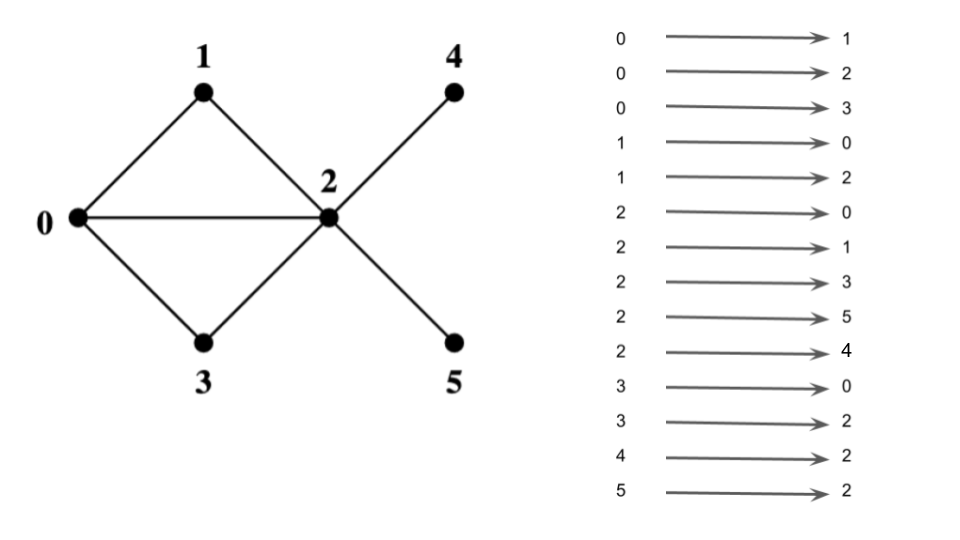

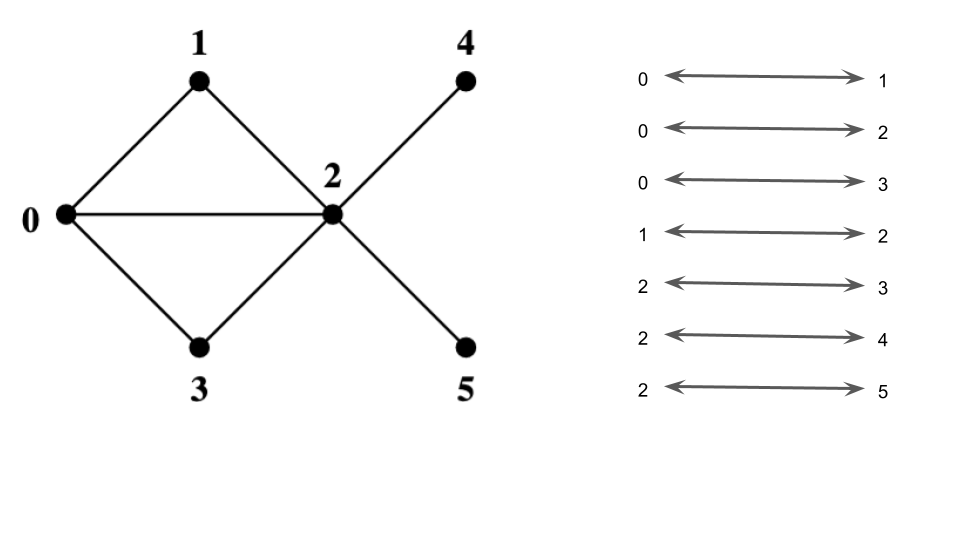

Adjacency lists

For each vertex, store the list of its neighbors

![[sample graph]](images/sparse.png)

Collection:

- classical approach: linked list

- vectors

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // Create a vector of length n of empty vectors let mut graph_list : Vec<Vec<usize>> = vec![vec![];n]; // iterate through the node pairs for (v,w) in edges.iter() { graph_list[*v].push(*w); graph_list[*w].push(*v); // for undirected, v is also connected to w }; for i in 0..graph_list.len() { println!("{}: {:?}", i, graph_list[i]); }; println!("{:?}", graph_list[2].binary_search(&3)); println!("{:?}", graph_list[1].binary_search(&3)); }

0: [1, 2, 3]

1: [0, 2]

2: [0, 1, 3, 4, 5]

3: [0, 2]

4: [2]

5: [2]

Ok(2)

Err(2)

Adjacency matrix

- vertices

- matrix

- For each pair of vertices, store a boolean value: edge present or not

- Matrix is symmetric for undirected graph

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // make a vector of n vectors of length n // initialized to false let mut graph_matrix = vec![vec![false;n];n]; // iterate and set entries to true where edges exist for (v,w) in edges.iter() { graph_matrix[*v][*w] = true; graph_matrix[*w][*v] = true; }; for row in &graph_matrix { for entry in row.iter() { print!(" {} ",if *entry {"1"} else {"0"}); } println!(""); }; println!("{}", graph_matrix[2][3]); println!("{}", graph_matrix[1][3]); }

0 1 1 1 0 0

1 0 1 0 0 0

1 1 0 1 1 1

1 0 1 0 0 0

0 0 1 0 0 0

0 0 1 0 0 0

true

false

Sample Graph Recap

This lecture's graphs:

- undirected

- no self-loops

- self-loop: edge connecting a vertex to itself

- no parallel edges (connecting the same pair of vertices)

Simplifying assumption:

- vertices labeled

What if labels are not in ?

For example:

- nodel labels are not numbers, e.g. strings

Ttype of labels

Solution 1: Map everything to this range (most common)

- Create hash maps from input labels to

- Create a reverse hash map to recover labels when needed

Solution 2: Replace with hash maps and hash sets (less common, harder to use)

- Adjacency lists: use

HashMap<T,Vec<T>>- first node is the key and values is the adjacency list

- Adjacency matrix: use

HashSet<(T,T)>- Sets of tuples where node pairs that are connected are inserted

- Bonus gain:

HashSet<(T,T)>better than adjacency matrix for sparse graphs

What if the graph is directed?

Adjacency lists:

- separate lists incoming/outgoing edges

- depends on what information needed for your algorithm

Adjacency matrix:

- example: edge and no edge in the opposite direction:

matrix[u][v] = truematrix[v][u] = false

- Matrix is no longer symmetric